Like many others, we at Insurgent Notes have been paying a great deal of attention to the events in Ferguson, Missouri, that began with the murder of Michael Brown in August. We have been inspired by the courage, determination and endurance of the people from Ferguson, and other nearby cities, that have refused to let his murder simply pass by—in spite of the overwhelming police/military power that has confronted them.

Introduction

I am completing this article, in mid-November, as news reports indicate that the grand jury’s decisions will be announced in the near future. Unlike perhaps too many others, however, I do not intend to offer unsolicited advice to the young activists who have maintained a steady presence on the streets about what they should do next. They did well enough on their own at the beginning and they have undoubtedly learned from the events of the last two months. By way of example, a recent article on VICE described developments within the movement this way:

Some protesters had never really thought much about the civil rights movement before, let alone imagined that their activism would be likened to it.

“I thought it was just a protest, but my brother, who’s a little older than me, was like, ‘No, this is a civil rights movement,” Dontey Carter, a leader of the Lost Voices and a regular presence at the protests, told VICE News. “I was like, ‘Really?’ I didn’t really put it in that perspective. I thought I was just a protester, but he’s like, ‘No, you’re a civil rights leader,’ and I was like, ‘Wow…’ ”

Carter, a 23-year-old former Crips member and a father of two small children, had never been to a protest prior to August 9, when Brown was shot. He was at a friend’s house in Ferguson when he saw television news broadcasts of the crowd assembling on Canfield Drive.

“I went down there and people started protesting and standing up, and I was like, ‘This is where it’s at,’ ” he said. “Me being there by myself felt kind of weird, but when we all did it together, it was amazing.”

By the time Brown was buried at a funeral attended by thousands of people, Carter and nine others he met on the streets had formed the Lost Voices—a group of Ferguson youth that camped out on West Florissant Avenue, the epicenter of the protests, for weeks before police eventually removed them, as Carter put it, “because we were taking too much of a stand.”

But that was just the beginning.

“It went bigger than camping out. Camping out was just to make a statement, to show that we would not be moved,” Carter said. “The officers talked to the business owners, saying that they would get some type of violation, but we still kept the movement going.”

The group was at “ground zero,” as its members called it, every night—facing SWAT teams, tear gas, and even a noose that someone left in a parking lot near their encampment. When VICE News spoke with two girls from the group at Brown’s funeral, they told us they called themselves Lost Voices because they wanted to speak for a generation of poor and marginalized black youth who had never been listened to.

Less than two months later, the group had gained dozens of friends in Ferguson and hundreds of supporters on Facebook. In October they dropped the “lost” and changed their name to Found Voices.

“Once we were lost but now we are found,” Carter said. “We were the Lost Voices but then people got a hold of who we really are, what this movement is truly about. It became our voice. We’re not lost anymore.”

Carter described the past two months as a “spiritual awakening.”

“My life changed radically,” he remarked. “I had friends die left and right—drugs, gangs, violence—and I’ve pulled away from all of that working for the movement.”

He’s not the only one. Ferguson’s black community became united during the protests, with groups setting beefs aside to march on the streets with a common purpose. Protesters recognize that police brutality is just one form of violence that intrudes on their lives. As they work to redress this, they have also come together in other ways.

“There was so much depression going on around here. It’s hard for you to actually think straight, to do something with yourself, cause there’s so much around you that’s negative,” Carter said, adding that the movement has changed that. “It wasn’t all about me. Other friends that were all about gangs and violence, they let all of that go, and they stood together. They weren’t too concerned about any of the stuff that was going on beforehand.”

“People are gonna wake up, they’re gonna take the wool off their eyes, and they’re gonna see the truth, cause only the truth can set you free,” he went on, switching into the protest leader role he naturally adopted. “I’ve seen the truth. I understand what’s going on. I understand how the system works, and I just want the people that’s unaware of what’s going on to be conscious of how the system works.”

On the other hand, I do have some ideas about the larger set of circumstances that resulted in Michael Brown’s murder and some suggestions for things that might be done to bring the fight where it needs to be fought beyond the streets of Ferguson.

My major points will be the following:

- There are, somewhat predictable, scripts of reaction, which the police, their organizations, the prosecutors, the elected officials, and even many of those who oppose what the police do follow in the aftermath of police killings and it would be wise if we recognized their unfolding.

- The events surrounding Michael Brown’s murder are the product of a complex set of historical developments in the St. Louis area. Those developments include: the central place of Missouri in the struggle over slavery; patterns of racial discrimination across the better part of the twentieth century; deindustrialization and the emergence of the financial and real estate sectors as centers of economic activity over the last forty years; policing practices; and the development of a “new whiteness” in the post–Civil Rights era.

- The key to mounting a fight against police harassment, assaults, and killings is to break up the social bloc that supports the cops. In the case of the St. Louis area, this bloc largely resides in the suburbs with large numbers of white residents that are the legacy of almost one hundred years of making segregation.

The Scripts

As most readers will probably know, police killings are not all that uncommon. When they occur, a somewhat typical train of events ensues. The authorities (at the local and federal levels) promise investigations. The police unions quickly insist that no one should pre-judge the cop involved. Indeed, they usually claim that there’s a good chance that the victim had been involved in some kind of criminal behavior and/or that he (almost always) had engaged in threatening behavior. In the Michael Brown case and that of Eric Garner in Staten Island (in New York City), those arguments needed to be softened a bit because of the availability of video evidence about what had actually happened.

In any case, after the killing has occurred, legal proceedings are initiated which stretch out for as long as possible—to buy time for the anger that emerged in response to the killing to die down. In Ferguson, this approach has not worked very well because those on the streets have been determined to refuse to let the anger “die down.” Michael Brown’s reputation was still fair game, however. During the drawn-out proceedings, leaks from various sources are used to suggest that, once again, the victim was not a law-abiding citizen in the past and that perhaps there is good reason to suspect that he got what he more or less deserved. Meanwhile, efforts to support the accused killer are put into full gear—support organizations are formed, funds are raised, buttons are sold and rallies are held. Not surprisingly, relatives and friends of police officers play a prominent role in these efforts. And everyone waits to see what the grand jury will do.

Which brings us to the moment that we’re at now. Many are convinced that no charges will be made against Officer Wilson; some (including this writer) think that the grand jury will return a number of less than really serious indictments with the expectation that Officer Wilson will be found innocent of the most serious and possibly guilty of the least serious; almost no one seems to believe that he will face serious charges.

Different groups are preparing. The police equip themselves with more weapons to use against protesters and develop plans for how they’re going to deal with various scenarios of violence and the governor considers calling out the National Guard.[1]

Some, mostly well-meaning folks, offer suggestions for how to keep things under control. See, for example, the statement of the Don’t Shoot Coalition

Other radical groups are preparing to urge the activists in Ferguson to return to the streets and engage once again in rebellious, if not riotous, actions. As I mentioned above, I’ll abstain from giving advice to the activists on the streets of Ferguson. But I do have some advice for others:

- They should not cooperate with the government.

- They should pay more attention to the social base of the support for Officer Wilson and try to imagine how they might mount a challenge to that support in the communities where it is concentrated. In other words, they should think about confronting not just the police on the streets of Ferguson but their supporters across the white belt of suburbs around St. Louis.

Which is why I’ll now turn to an effort to understand the historical development of that base of support.

Historical Developments

Missouri—Not Far From the Center of the Country

If we leave out Alaska and Hawaii, the geographical center of the United States is in northern Kansas, but Missouri, its neighboring state, has probably played a more central role in the nation’s history. Missouri was among the territories claimed by the United States under the terms of the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, part of the fallout of the defeat of Napoleon’s army by the free people of Haiti. From soon afterwards, slavery was the defining issue.

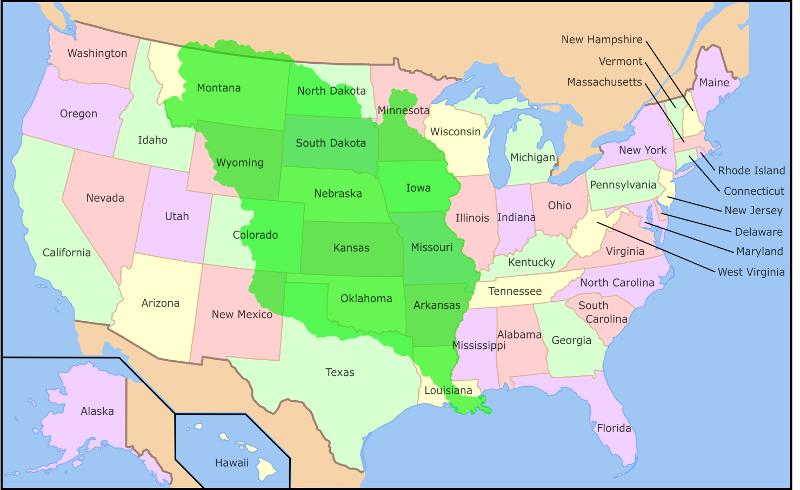

In 1820, Missouri was admitted to the Union as a slave state along with Maine as a free state. At the same time, the so-called Missouri Compromise prohibited the extension of slavery to any other parts of the territory covered by the Purchase (territory that includes what is now Arkansas, Missouri, Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota, northeastern New Mexico, northern Texas, Montana, Wyoming and Colorado, as well as Louisiana west of the Mississippi River). Here’s a map with.a bit of an explanation of the geography:

While slavery was legal in the state, not all African Americans were enslaved. This seems to have especially been true in St. Louis. Furthermore, as was the case in many Southern cities, slaves who could perform various kinds of skilled labor were often “rented out” to individuals or businesses. To some extent, these workers were able to move around the city. As a result, both free and enslaved individuals were in frequent contact with each other. At the same time, this hardly meant that slavery was not a permanent reality, and St. Louis became a major center for the buying and selling of slaves. By the 1840s, about 5 percent of the population in St. Louis was black—approximately two-thirds of whom were enslaved. As elsewhere, the stage was set for a battle between the supporters and opponents of slavery.

The Road to the Civil War

Elijah Lovejoy moved to Missouri in 1827 and became the editor of the St. Louis Observer He subsequently became a.Presbyterianminister and established a church. His Observer editorials criticized slavery (he identified himself as an abolitionist—in favor of the abolition of slavery) and other church denominations for their failure to do the same. In May 1836, after anti-abolitionist opponents in St. Louis destroyed his printing press for the third time, Lovejoy moved across the Mississippi River to Alton, Illinois (a free state). He began publishing the Alton Observer On November 7, 1837, a pro-slavery mob attacked the warehouse where the printing press was housed. Lovejoy and his supporters exchanged shots with the mob and he was fatally wounded. He became an abolitionist hero.

In 1846, Dred Scott (a slave who had often been “rented out”) sued for his, his wife’s and their two daughters’ freedom in St. Louis. Scott had traveled with his owner John Emerson, a surgeon in the United States Army, who was frequently transferred to different army bases. During these transfers, Scott spent time in Illinois, a free state, and the Wisconsin Territory, now Minnesota—where slavery was prohibited because of the terms of the Northwest Ordinance of 1787. .[2] Subsequently, the army transferred Emerson to St. Louis and then to Louisiana (places where slavery was legal). After getting married in Louisiana, Emerson commanded the Scotts to return to him. They did so.

The Emersons and the Scotts returned to Missouri in 1840. In 1842, Emerson left the army but died soon afterward. His widow inherited his estate, including the Scotts. For three years after Emerson’s death, she continued to hire out the Scotts. In 1846, Scott attempted to purchase his and his family’s freedom, but Mrs. Emerson refused, leading Scott to file his suit in St. Louis Circuit Court. The Scott v. Emerson case was first tried in 1847. The judgment went against Scott but the judge called for a retrial because of problems with the evidence. In 1850, a second jury found that Scott and his wife should be freed since they had been illegally held as slaves during their time in the free jurisdictions of Illinois and Wisconsin. Mrs. Emerson appealed. In 1852, the Missouri Supreme Court struck down the lower court ruling, and ruled that the precedent of “once free always free” was no longer the case, overturning 28 years of legal precedent.

Under Missouri law at the time, after Dr. Emerson had died, the powers of the Emerson estate were transferred to his wife’s brother, John Sanford. Because Sanford was a citizen of New York, Scott’s lawyers argued that the case should be brought before federal courts. After losing again in federal district court, they appealed to the United States Supreme Court.

On March 6, 1857, Chief Justice Taney delivered the majority opinion. The Court ruled that any person descended from Africans, whether slave or free, was not a citizen of the United States and that neither the Ordinance of 1787 nor the Missouri Compromise legislation could grant either freedom or citizenship to non-white individuals. The Court also ruled that because Scott was the private property of his owners he was subject to the provision of the Fifth Amendment that prohibited the taking of property from its owner “without due process.”

Following the ruling, Scott and his family were returned to Emerson’s widow. Due to changes in Mrs. Emerson’s circumstances (she had married into an abolitionist family), the Scott family was set free less than three months after the decision. While the consequences of the decision were not devastating to the Scotts, the decision nonetheless made clear the determination of the slave power to preserve the bondage of millions of people.

Scott went to work as a porter in a St. Louis hotel but died less than two years later. He was originally interred in Wesleyan Cemetery in St. Louis, but his coffin was later moved to the Catholic Calvary Cemetery.[3]

A video filmed in the cemetery offers a moving appreciation of the significance of Dred Scott and the decision that bears his name.

Scott’s wife survived him by 18 years and there are descendants of the family still living in the St. Louis area.[4]

The prohibition against slavery in the Louisiana Purchase territories had already been effectively ended by the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854, which stipulated that the slave or free status of those states would be decided by the popular sovereignty (votes) of white males. That legislation opened up the chapter now known as Bloody Kansas, in which slavery supporters from Missouri served as shock troops to terrorize those who had moved to Kansas to oppose slavery. Which brings us to John Brown in Missouri.

In December 1858, Brown heard that a slave named Daniels from Missouri had crossed into Kansas looking for assistance in rescuing his family from sale to another slave owner. By the next day, Brown had organized a raiding party of nearly twenty abolitionists. The band split up into two groups so that they might be able to free other slaves on the same trip. Brown’s group captured Daniels’s owner, Harvey Hicklan, and rescued the Daniels family. All told, the two groups freed eleven slaves. Slave owners and their supporters were outraged by the theft of property and the killing of one of their own that had taken place during the raid. The governor of Missouri offered a $3,000 reward for Brown’s capture immediately afterward.But Brown was not done. For three winter months, he led the rescued slaves across Nebraska and Iowa. Along the way, anti-slavery folks provided food, clothing, accommodations and protection for the fugitives. The freed people secretly boarded a train to Chicago and another one to Detroit. Finally, they took a ferry to freedom in Windsor, Canada. But John Brown did not rest. The Missouri raid launched him on the last great deed of his life—the assault on the arsenal at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia, in October 1859. Although the assault failed and Brown was executed, it “startled the South into madness” and led step by step to the war of slave emancipation.[5]

The Civil War

While Missouri had been a slave state, it was not clear which side it would be on during the Civil War. In part, this was the result of the arrival of large numbers of German immigrants in the St. Louis area during the 1850s. Some of them were refugees from the failed German revolution of 1848, and some were followers of Karl Marx, including Joseph Wedemeyer.[6] They began to make their presence felt in 1861. On New Year’s Day, German immigrants stormed a slave auction to stop it from going forward. At the same time, the St. Louis Arsenal housed a large supply of weapons and ammunition. The pro-slavery governor of the state launched a plan to seize it. German immigrants with some Irish and native-born allies mobilized against the plot. Eventually more than 5,000 men assembled to protect the arsenal. When the Confederate supporters attempted an attack on the arsenal, they were overwhelmed by a superior force and surrendered without a fight. Soon afterward, many of those German immigrants volunteered to serve in the Union Army, but not much actual fighting took place in Missouri.

After the end of the war, Missouri adopted a new state constitution that prohibited slavery and required that African-American children be enrolled in schools (that would only enroll black children). Soon afterward, the passage of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution and the establishment of Reconstruction governments across the South appeared to herald a new day. But the promise would not last and the end was tragic. Instead, the Reconstruction era launched at the end of the war ended in tragedy, with all of the promise of emancipation squandered, and, as W.E.B. Du Bois commented, “Democracy died, save in the hearts of Black folk.”[7]

The Making of a Segregated Metropolitan Area

During the last third of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth, the black population of St. Louis grew. Black and white residents mostly lived in separate parts of the city but housing conditions were not necessarily worse in the black sections. But soon enough, whites adopted a method to their madness. In 1915, voters approved a local law that prohibited any one from moving to a block where more than 75 percent of residents were of a different race. When the law was overthrown by a court decision, the St. Louis Real Estate Board supported the establishment of neighborhood associations whose members signed fifty-year covenants forbidding sales to non-whites. That practice would not be outlawed until a Supreme Court decision in 1949.

In the years before fair housing laws passed, black real estate brokers faced death threats, assault and bombings of their residences by angry whites intent on policing the color line. Furthermore, white vigilantes frequently attacked blacks that were attempting to move into white neighborhoods or to use whites-only recreational facilities. According to George Lipsitz,

When the city of St. Louis announced the desegregation of its municipally owned and operated swimming pool in Fairgrounds Park in 1949, thirty Black children showed up for a swim. More than two hundred whites brandishing weapons and shouting racist epithets surrounded the pool to drive them out. Police officers escorted the Black youths to safety, but whites began attacking Blacks they encountered in and around the park. By nightfall, five thousand whites assembled at the site. They cornered Black pedestrians, attacking them with lead pipes, baseball bats, and knives. Two white men advised the crowd to “get bricks and smash their heads.” Police officers restored order temporarily but in response to the upheaval the city rescinded the desegregation order and closed its pools entirely.[8]

In that same year, the American Housing Act dramatically expanded the role of the federal government in urban renewal and the construction of public housing. In St. Louis, the Land Clearance and Redevelopment Authority expanded the Gateway Mall (a green belt that stretches from the Arch at the Mississippi River through downtown) by tearing down what were considered to be slums, and the Housing Authority quickly launched plans for the building of 5,000 units of low-rent public housing in five major locations—Plaza Square, Cochran Gardens, Darst-Webbe, the Vaughn Apartments and the Pruitt-Igoe Apartments. While the “projects” were initially welcomed as a great benefit and were somewhat integrated, they quite rapidly lost their appeal; the white residents left and, as the developments filled with black tenants, they were effectively abandoned. Soon enough, many of those black residents left for other dwellings.[9]

By the end of the 1960s, blacks had been crowded into the north side of the city. In How Racism Takes Place, George Lipsitz summarized the developments:

In a city where direct discrimination confined Blacks to an artificially constricted housing market, landlords and real estate brokers were free to charge them high costs for inferior and unhealthy dwellings. Slum clearance, urban renewal, and redevelopment programs made a bad situation worse by bulldozing houses inhabited by Blacks without providing adequate replacement housing. The majestic Gateway Arch on the river-front, the corridor of municipal buildings and parks near City Hall and Union Station, the midtown redevelopment area near St. Louis University, and the downtown baseball and football stadia all stand on land formerly occupied by housing available to Blacks. Seventy-five percent of the people displaced by construction of new federal highway interchanges in the downtown area were Blacks. Redevelopment in the Mill Creek Valley area alone displaced some twenty thousand Black residents, creating new overcrowded slums in the areas into which they were able to relocate.[10]

From the 1930s through the 1960s, the Federal Housing Administration used strict “redlining” guarantees to determine eligibility for its subsidized home mortgage loans. In the 1950s and 1960s, the federal government’s highway building program increased the value of homes in racially exclusive suburbs. Lipsitz writes about St. Louis:

Even after direct references to race disappeared from federal appraisers’ manuals, race remained the crucial factor in determining whether borrowers receive federally supported mortgage loans. Only 3.3 percent of the 400,000 FHA mortgages in the greater St. Louis area went to Blacks between 1962 and 1967, most of them in the central city. Only 56 mortgages (less than 1 percent ) went to Blacks in the suburbs of St. Louis County. Three savings-and-loan companies with assets of more than a billion dollars worked together to redline the city effectively, lending less than $100,000 on residential property inside the city limits in 1975. The local savings-and-loan institutions made loans totaling $500 million in the greater St. Louis area in 1977, but just $25 million of that total (less than 6 percent ) went to the city, almost all of it to the two mostly whites zip codes at the municipality’s southern border.[11]

A 1990 survey reported that St. Louis was the eleventh-most segregated city among the more than two hundred largest metropolitan areas in the United States. (The stark character of the segregation is well known in St. Louis and is reflected in the common use of the term “Delmar Divide” to specify the boundary between white and black St. Louis. The “Divide” has even become the topic of a BBC documentary.)

While the disadvantages of segregation for blacks are often enough acknowledged, what is not usually acknowledged are the advantages for “whites.” Lipsitz argues:

Although many of the practices that secured these gains initially were outlawed by the civil rights laws of the 1960s, the gains whites received for them were already locked in place . Even more important, nearly every significant decision made since then about urban planning, education, employment, transportation, taxes, housing, and health care has served to protect the preferences, privileges and property that whites first acquired from an expressly and overtly discriminate market [emphases added].[12]

For the white folks, their relative advantages led them “to believe that people with problems are problems, that the conditions inside the ghetto are created by ghetto residents themselves.”

Not surprisingly, many of the black people held more or less captive in undesirable circumstances in the city of St. Louis looked to get out. But they did not escape the effects of segregation. Once again, Lipsitz:

Since the 1970s, Blacks have gradually started moving to the suburbs. Yet Black suburbanization is largely concentrated in areas with falling rents and declining property values, most often in older inner ring suburbs. For example, census tracts that had more than 25 percent Black populations in St. Louis County in 1990 were concentrated in one corridor adjacent to the city’s north side. Suburbs with Black populations above 60 percent (Bel Ridge, Berkeley, Beverly Hills, Hillsdale, Kinloch, Northwoods, Norwood Court, Pagedale, Pinelawn, Uplands Park, and Wellston) lay in contiguous territory outside the city limits.[13]

Things have not changed much since. Earlier this year, researchers at Washington University and St. Louis University reported that African Americans constituted between 45 percent and 97 percent of the population in the zip codes covering the northern part of the city and the suburban cities just north of them (including Ferguson). At the same time, in the zip code areas south and west of the city, African Americans constituted less than 5 percent of the population.

This profound cleavage and the sharp differences in living conditions and life possibilities that it both creates and symbolizes has left its marks in the minds of the residents of both the white and the black communities. Here’s an illuminating, and contemptible, recent video by a white man traveling in his car through the heart of the black community of St. Louis.

I wasn’t able to find any comparable travelogue produced by a black journey through the white suburbs, but I believe that it’s not too hard to imagine why we have witnessed the extraordinary solidarity on the streets of Ferguson. That solidarity “stems not so much from an abstract idealism as from necessity. Pervasive housing discrimination and the segregation it consolidates leaves Blacks with a clearly recognizable linked fate. Because it is difficult to move away from other members of their group, they struggle to turn the radical divisiveness created by overcrowding and competition for scarce resources into mutual recognition and respect.”[14]

Deindustrialization, the FIRE Economy and Policing in the Post–Civil Rights Era

At more or less the same time as the segregated world of St. Louis was being solidified, momentous changes began to change the shape of the United States economy and the lives of people across the country. St. Louis was in the center of the maelstrom.

Let’s go back. By 1900, St. Louis had a population of 575,000 people (the fourth largest in the country at a time when New York City’s population was about 3.5 million) and had become a large manufacturing and transportation center. By 1930, it had grown to about 820,000 people while New York had doubled to just under 7 million. The city was still a vibrant center of manufacturing. But, starting with the beginning of the Depression, the city lost half of its manufacturing production; more than 30 percent of the population was unemployed and black unemployment was at 80 percent. Only with the introduction of large scale war production in anticipation of the entry of the United States into World War II, and the further expansion of that production once the United States joined the conflict, did the number of jobs and residents increase again. But the uptick was short-lived and, as soon as Japan surrendered, war contracts were terminated and thousands lost their jobs. By 1960, the city’s population had declined to about 750,000. To some extent, the decline within the city was offset by the rapid suburbanization that took place afterward—made possible by the construction of new highways and thereby spreading the population ever further away from the center of town.[15] However, a relatively high level of industrial employment was maintained until the 1970s. But then the bottom started falling out—between 1979 and 1982, St. Louis lost 44,000 industrial jobs. This led to the loss of still more people from the city.

The decline of St. Louis reflected the emergence of a new era in American social and economic life—an era characterized by:

- factory closures and plant transfers to lower-waged locations;

- elimination of jobs through automation;

- extensive technical innovation in communication, transportation and production—resulting in still more job losses;

- the development of finance as a major source of profits (even for industrial firms);

- a rise in part-time or temporary jobs as primary employment;

- the depopulation and physical destruction of cities (such as St. Louis, Detroit, Baltimore);

- gentrification in many urban neighborhoods and the rise in political importance of the social groups formed by that gentrification (although this is not much of a reality in St. Louis);

- sharp decreases in unionization rates in the private sector;

- lowered wages and reduced benefits;

- the establishment of credit (at either normal or usury rates) as an indispensable way of life for many members of the middle and working classes.

These large developments have had specific features in St. Louis.

Land and property have been important for a long time. The importance they have in cities is quite different from the importance they have elsewhere. Within the cities, the value of the land has little to do with its fertility or the resources hidden beneath its surface. Instead, it has a great deal to do with relative desirability. Residential real estate speculation within cities has been preoccupied with manipulating desirability—most recently symbolized by gentrification. But gentrification, at least in the forms that it has taken in cities like Washington and New York, has not been a major development in St. Louis. At the same time, commercial real estate speculation has been preoccupied with the value of attractions—things that bring people with money to places where they will spend it—museums, monuments, theaters, parks and sports arenas. This speculation has constituted the predominant model of urban economic development for the last few decades and has fostered intense inter-city and intra-city competition to provide developers with the most favorable terms. Which brings us to professional sports.

Lipsitz begins his third chapter, “Spectatorship and Citizenship,” with a sports story—the St. Louis Rams’ win in the 2000 Super Bowl over the Tennessee Titans:

When the St. Louis Rams defeated the Tennessee Titans on January 23, 2000, to win the National Football League Super Bowl championship, the team’s players, coaches, and management deserved only part of the credit. Sports journalists covering the games cited the passing of Kurt Warner and the running of Marshall Faulk as the key factors in the Rams victory. Others acknowledged the game plan designed by head coach Dick Vermeil and the player personnel moves made by general manager John Shaw. But no one publicly recognized the contributions made by 45,473 children enrolled in the St. Louis city school system to the Rams’ victory. Eighty-five percent of these students were so poor that they qualified for federally subsidized lunches. Eighty percent of them were African-American. They did not score touchdowns, make tackles, kick field goals, or intercept passes for the team. But revenue diverted from the St. Louis school system through tax abatements and other subsidies to the Rams made a crucial difference in giving the football team the resources to win the Super Bowl.[16]

While the schools were starving, tax deals like the one for the Rams were taking away seventeen million dollars every year from public education.

Lipsitz argues that the stadium “would have never been built without government funds and subsidies—because stadiums don’t make money,” and he explains that recovering the costs involved in the debt for the construction would require the scheduling of a total of more than 500 “events” in the stadium each year—an obviously impossible possibility. But Lipsitz reminds us that the actual debt is only part of the story—debt demands interest. He writes, “At least twenty-four million dollars a year in city, county, and state tax dollars will continue to be spent on the St. Louis stadium project through the year 2022.” But even that’s not enough—provisions of the contract that the Rams have with the city allows the team to leave for still another city if the subsidies don’t match what other teams are getting or if the stadium’s attractions are considered not as good as those in other places. Lipsitz bitterly comments:

The Rams can always move again. After all, they were the Cleveland Rams before they were the Los Angeles Rams. Even inside Los Angeles, the team moved from the Los Angeles Coliseum to Anaheim Stadium after officials in that suburban city expanded the size of their facility from 43,250 to 70,000 seats, constructed new executive offices for the team’s use, and built 100 luxury boxes for use by Rams fans.

…

Subsidies to previous franchises did not prevent St. Louis from losing the basketball Hawks to Atlanta or the football Cardinals to Phoenix. In fact, by using subsidies to provide the Rams with more profit in a metropolitan area with three million people than they could get in one with more than nine million, the backers of the stadium have unwittingly increased the number of their potential competitors. With subsidies like these, professional football franchises can move virtually anywhere and make a profit. The Tennessee Titans, defeated by the Rams in the 2000 Super Bowl, previously played in Houston as the Oilers, until a subsidized stadium in Nashville persuaded team owner Bud Adams to move his operations there. He could make more money in a smaller city because of government subsidies.[17]

In 1975, state and local governments sold $6.2 billion of tax-exempt bonds for commercial projects; by 1982, the total was $44 billion. At the same time, bond sales for the construction of schools, hospitals, housing, sewer and water mains, and other public works projects declined. According to Lipsitz:

Twenty-nine new sports facilities were constructed in US cities between 1999 and 2003 at a total cost of nearly nine billion dollars. Sixty-four percent of the funds to build those arenas—approximately $5.7 billion—came directly from taxpayers. In Philadelphia, construction of a new baseball stadium for the Phillies and a new football stadium for the Eagles cost $1.1 billion. City funds supplied $394 million, and state tax revenue contributed an additional $180 million.[18]

Just recently, the City of Detroit, in spite of being bankrupt, agreed to contribute $200 million in tax increment financing to subsidize the construction of a new arena for the Detroit Red Wings hockey team.[19]

This pattern reflects an intense competition between different cities which “produces new inequalities that can be used in a race to the bottom by capital, promoting bidding wars between government bodies to reduce property taxes and other obligations while increasing subsidies and the provision of free services to corporations.” Lipsitz argues:

The subsidies offered to support structures like the domed stadium in St. Louis proceed from this general pattern. In the Keynesian era, St. Louis financial institutions invested in their own region. But since the 1980s they have been shifting investments elsewhere, exporting locally generated wealth to sites around the world with greater potential for rich and rapid returns. Building the domed stadium offered them an opportunity to create a potential source of high profit for outside investors in their region. Large projects like this generate some new short-term local spending on construction, financing, and services. They clear out large blocks of underutilized land for future development. But because they are so heavily subsidized, projects like the domed stadium wind up costing the local economy more than they bring in while they funnel windfall profits toward wealthy investors from other cities.

The ability of local and state governments to sell these projects depends fundamentally on the genuine popularity of professional sports, especially football. Lipsitz has something interesting to say about this:

[P]rofessional sports fill a void. They provide a limited sense of place for contemporary urban dwellers, offering them a rooting interest that promises at least the illusion of inclusion in connection with others. The illusion is not diminished by contrary evidence, by the fact that every St. Louis Ram would become a Tennessee Titan and every Tennessee Titan would become a St. Louis Ram tomorrow if they could make more money by doing so, by the fact that team owners preach the virtues of unbridled capitalism while enjoying subsidies that free them from the rigors of competition and risk, by the fact that impoverished and often ill schoolchildren are called upon to subsidize the recreation of some of the society’s wealthiest and healthiest citizens.[20]

Policing in the Post–Civil Rights Era

Everyday in Ferguson, its surrounding areas and all across the country, the police stop, mostly young, black men. Most of the everyday encounters are not recorded—other than in the memories of the young people themselves and, in quite different ways, in the memories of the cops involved—for others to see. If recordings were available, what we’d likely see are encounters that include verbal and physical abuse designed to intimidate and humiliate—cops reaching into the young men’s pants, pulling down their pants, throwing them to the ground or against a wall. In virtually all of these instances, the cops have the upper hand—they have the handcuffs, clubs and guns; they have their fellow cops ready to back them up; they have the ability to fabricate charges and they can rely on the slow administration of justice to make sure that they will face no consequences. Perhaps others can understand why the young people are outraged at what happens to them and why the cops may very well be terrified because of their understandable concern that the young people have not forgotten and, as they have done in Ferguson, that they might take things into their own hands and that others might join with them.

Perhaps it’s this fear that we see when we look at what happens when shots are fired and the cops are involved—a cop shoots somebody or, less often, somebody shoots a cop. In either case, lots of cops arrive in minutes, with sirens screaming, from all directions—they put up their yellow tape and they tell everyone to keep away. They answer no questions and they threaten anyone who keeps asking. They make sure that the cop involved is quickly removed from the scene. The contrast with what the cops did after Michael Brown was shot is excruciating—there they arrived in their usual numbers and they made sure that people stayed away but there was no urgency about Michael Brown—he was just left lying on the ground for hours. It would be a really good question to ask them—WHY? Dead was not enough?

In the aftermath of the shooting, the National Association of Police Organizations (NAPO) was quick to come to Darren Wilson’s defense. It purchased newspaper ads and wrote letters to people like Attorney General Eric Holder. Its arguments were not vulgar ones—they insisted that the facts were not yet known and that people should wait to see what the investigations revealed. Its messages are clearly designed to shape the ways in which cops across the country think about and talk about the issues and, in turn, to shape the ways in which the supporters of the police think and talk about them.[21] NAPO is no two-bit operation. It currently includes organizations that represent approximately 240,000 police officers (including cops in Boston, Chicago, Dallas, Detroit, Houston, Las Vegas, New Orleans, New York and Portland, as well as St. Louis) and 100,000 civilian supporters. They all stand ready to defend cops just about anywhere.

As is often the case, the details of the regularly awful things that happen everyday only emerge into daylight when something “really awful” happens—as with the killing of Michael Brown. In the cities north of St. Louis and in Ferguson, in particular, the everyday routines of police harassment of black people have taken on a particularly mercenary character. It appears that, because Ferguson is a small city and does not have the real estate tax base that it needs to support its budget (in spite of the fact that the city is home to a Fortune 500 corporation, Emerson Electric), the city relies heavily on public safety and court fines that have skyrocketed in recent years.[22] A recent review of the city’s financial statements indicated that court fines accounted for twenty percent of its revenue. The city took in more than $2.5 million in court revenues in the last fiscal year, an 80 percent increase from two years earlier. This is no accident—it’s a business plan. A local law professor, Bryan Roediger, estimates that the court—which only holds three sessions a month—heard 200 to 300 cases an hour on some days. A recent report also argues that the court routinely begins hearing cases 30 minutes before the scheduled start time and then locks the doors 5 minutes after the official start. Those who arrive late face an additional charge for failing to appear. According to Governing, “the Ferguson Municipal Court disposed of 24,532 warrants and 12,018 cases in 2013, or about 3 warrants and 1.5 cases per household.”

Ferguson is not the only city that plays the traffic stop game. Often enough, when someone is stopped in one jurisdiction, it’s discovered that there are outstanding warrants in other ones. As a result, the person gets sent first to one jail until a bond is posted, then to another and then to another—with money being collected at each stop along the way.

The anger that is fueling the rebellion in Ferguson has been shaped day in and day out by these experiences for many years. A reporter from. VICE suggested that the scope of the anger is “best captured by one of the protesters’ favorite slogans: ‘ The whole damn system is guilty as hell.’ ”[23]

A New Whiteness

As many have argued, whiteness is historical. It is not a natural condition—like being left-handed. Over time, groups once excluded from it were allowed in. The only group permanently excluded was the blacks. But these last two decades or so had provided a good deal of evidence to suggest that whiteness is not quite what it used to be—such as on the one hand, the presence of black individuals at the head of Fortune 500 corporations and, perhaps needless to say, the election of Barack Obama to the presidency and, on the other hand, the ineffectiveness of the traditional privileges of whiteness in protecting white workers from being thrown out of their jobs when the factories shut down. However, I’d like to suggest that the white question has not been settled.

In addition to the more or less open white supremacist groups on the far right, there are many who want to preserve, if not enhance, the privileges accorded to those considered white. Their convictions and their assumptions reflect the material circumstances of their lives as well as a good deal of absent-mindedness and historical amnesia. As George Lipsitz has convincingly argued, the legacy effects of previous discrimination are very significant and they are, in many ways, crystallized in the sharp demarcation between the concentrations of blacks in hollowed out center cities and in inner-ring suburbs and the wide dispersal of “whites” across the broad suburban landscapes around the cities. Lipsitz:

Racialized space enables the advocates of expressly racist policies to disavow any racial intent. They speak on behalf of whiteness and its accumulated privileges and immunities, but rather than having to speak as whites, they present themselves as racially unmarked homeowners, citizens and taxpayers, whose preferred policies just happen to sustain white privilege and power.

With or without being asked, many police officers have been actively engaged in enforcing the racial separations defined by space. At the same time, it is clear that there are some, perhaps many, in the highest political and economic circles who would prefer that policing be conducted in accordance with the protection of civil rights and civil liberties but, at least in this instance, they do not always have the last word.[24] The police’s jobs are to protect property and to deal with the all but inevitable consequences of the immiseration that has become pervasive in the last forty years—as a result of the transformations in the American economy described above. To a not insignificant extent, however, the police often act autonomously and they are seldom called to account when they do so. In that context, the power of police unions (especially as reflected in their ability to influence politicians seeking their support) plays a major part in maintaining their protection. These unions have come a long way—they seldom have any need for any recourse, at least publicly, to explicit pronouncements of any racial intent. The “new whiteness” is perhaps the lie that does not have to speak in its own name.

Conclusion

By way of a conclusion, I would repeat my earlier point about the central task of confronting the social bloc that the police count on for support. At the same time, it remains essential to support and defend those who have taken the lead in Ferguson. But, we should also not underestimate the need to address the profound shaping of the lives of the people involved by the larger set of circumstances created and sustained by the particular ways in which capital rules St. Louis.

- [1]In what might be considered a parallel process of attempting to control the situation (or to win over at least some local residents), institutions, such as Emerson Electric and St. Louis University, have committed themselves to various improvement efforts. See, for example, “Emerson donating $4.4 million for Ferguson scholarships, job training,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch and “Here’s the Agreement that Ended the Occupation of Saint Louis University,” Riverfront Times↩

- [2]. The Northwest Ordinances of 1787 and 1789 had prohibited slavery in the territory that now includes Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, Illinois, Wisconsin and part of Minnesota.↩

- [3]William Tecumseh Sherman, the Union Army General whose March to the Sea broke the back of the Confederacy and led to the North’s victory, is buried in the same cemetery.↩

- [4]The Gateway Arch in St. Louis, the defining feature of the city’s landscape, was designed as a memorial to the westward expansion of the United States (initiated by the Louisiana Purchase) and to the early European explorers. No memorial was built about the consequences of that expansion for the Native American peoples who were pushed off their lands. Subsequently, the Arch was incorporated within the Jefferson National Park to also include the city’s Old Courthouse (the scene of the two Dred Scott trials). The whole project seems to be a fitting symbol for the ways in which the writers of what we might consider the “good” version of American history want to have it both ways—celebrating the frontier and freedom while obscuring the ways in which, for many years, it was the official policy of the United States government to implement the genocide of the Native Americans and the slavery of those of African descent.↩

- [5]For more on John Brown, see W.E.B. Du Bois, John Brown, Modern Library Classics (2014).↩

- [6]Marx and Engels closely followed the developments in the United States leading up to the Civil War and during it. They wrote numerous articles about the events, a limited number of which are available online More important, they played a major role in ensuring that the International Workingmen’s Association would be a mainstay in the effort to prevent England from entering the war on the side of the South and to enforce a boycott of Southern cotton—even when it meant lost jobs for English factory workers.↩

- [7]. W.E.B. Du Bois, Black Reconstruction in America (The Free Press: 1988), p. 30.↩

- [8]George Lipsitz, How Racism Takes Place (Temple University Press: 2011), p. 26. Lipsitz’s book was an invaluable source for most of the information and analysis in this section.↩

- [9]At this point, only Plaza Square, which had been sold to private owners, remains standing. All of the others have been demolished. Most infamously, one of the Pruitt-Igoe buildings was blown up for the world to watch in 1972 (less than twenty years after they had been built). What remains in most instances are empty, and over-grown, lots.↩

- [10]Lipsitz, p. 76.↩

- [11]Lipsitz, p. 75.↩

- [12]Lipsitz, p. 3.↩

- [13]Lipsitz, pp. 55–56.↩

- [14]Lipsitz, p. 56.↩

- [15]These trends have continued for the last fifty years. In 2013, St. Louis’s population was down to approximately 318,000 (making it the fifty-eighth largest city in the country). At the same time that the city’s population was declining, the population in what is called the Metropolitan Statistical Area (that includes the suburbs) had grown to about 2,795,000. This means that the city itself only constitutes a bit over 10 percent of the population in the area. By comparison, New York City constitutes about 40 percent of the population in its area.↩

- [16]Lipsitz details the grim realities in the St. Louis public school system that were exacerbated by underfunding—underpaid and inexperienced teachers, a low high school graduation rate and a dropout rate that, at times, was more than three times the state average. See pages 73–74.↩

- [17]Lipsitz, pp. 90–91. In spite of all this, I suspect that George Lipsitz might be a Rams fan. If I’m right, I admire his willingness to share his analysis with the rest of us who are fans of other football teams or not fans of any.↩

- [18]Lipsitz, p. 86.↩

- [19]On Detroit, see “New Detroit Red Wings Arena: Plenty of Public Subsidies; Few Public Benefits,” Planetizen.↩

- [20]. Lipsitz, pp. 92–93.↩

- [21]The text of the message that NAPO sent to its members is available↩

- [22]. In 2009, Emerson Electric received state income tax credits and local property tax abatements to support its construction of a new computer center on its headquarters campus. Perhaps that’s why traffic stops had to increase↩

- [23]In 1941, CLR James wrote about the attitudes of sharecroppers who were fighting against their conditions in southeast Missouri that: “[T]hese workers, in a fundamental sense, are among the most advanced in America. For, to any Marxist, an advanced worker is someone who, looking at the system under which he lives, wants to tear it to pieces. That is exactly what the most articulate think of capitalism in southeast Missouri.” Perhaps the same might be said of the people on the streets of Ferguson in 2014.↩

- [24]I’d suggest that the dispatching of Attorney General Eric Holder to Ferguson to express his concerns and to promise an investigation was not just an exercise in going through the motions—they would really prefer that the cops be equal opportunity upholders of the law. It’s also the case that many of these same people have been responsible for and supportive of the equipping of police departments with battlefield quality weaponry and equipment—such as were seen on the streets of Ferguson and during the police occupation of Boston after the Boston Marathon bombing. Whatever their views might be on the question of race, there is no question about the extent of their commitment to the preservation of the rule of capital—by any means necessary.↩