I hope this essay makes sense. It’s intended to enable those of us associated with Insurgent Notes and others to imagine how we might contribute to the emergence of an emancipatory, anti-capitalist mass politics in the aftermath of the 2016 presidential election. The most important point that I want to make is that no variety of liberalism, progressivism or social democracy will be adequate for addressing the multiple global crises of capitalist society nor will they be adequate for providing a genuine alternative to the many millions of people who are drawn to varieties of populist or fascist politics. Put simply, only a large, international, anti-capitalist and socialist movement can provide the alternative to capitalism the people of the world need and an alternative that can defeat the challenge of what I’d call revolutionary reaction.

A central task in the development of that movement is the expansion of people’s understandings of politics beyond participation in electoral politics. Such an expanded understanding would have few limits and would include sustained engagement with all of the aspects of people’s daily lives at work, in their communities, and in their personal lives. But it cannot allow that engagement to result in a subordination of a commitment to a revolutionary transformation for all to the amelioration of the conditions of some. In that context, international solidarity will be indispensable.

It will also require some new ways of thinking and acting about what it means to “do politics.” At the end, this essay explores some aspects of what such new ways might look like.

In spite of hours of work on it, the essay is not complete and it needs the ideas of others to make it so. More than anything, it’s an invitation to others to respond. I would welcome the opportunity to talk with individuals or groups about the document—to answer questions, to clarify confusions and to push beyond where I leave off.

These are its parts:

- Setting the Stage for 2016

- On Trump and His Supporters[1]

- On Sanders and, by contrast, Rosa Luxemburg’s Opposition to “War as Such”

- Resemblances to the Past

- The Almost Fifty Years’ Assault on the Working Class

- The Moment and a Response

- Core Principles of a Strategy

- A New Start for Revolutionary Political Organization

- An Earlier Conjuncture

- Doing Politics: Notes from an Earlier Moment

- What Insurgent Notes Could Contribute

Setting the Stage for 2016

We need to make our own distinctive sense of the reasons for and the significance of the breaking apart of the United States electoral system that Dave Ranney described as a “vehicle to keep American common sense intact and unchallenged.” In 2014, Ranney wrote: “A system of perpetual and increasingly expensive elections, two dominant parties that have programs well within the New World Order system, and a media that channels all political discourse into the confines of electoral issues combine to eliminate any serious challenge to the system itself. As a result, elections, far from being an exercise of democracy, are a form of thought control.”[2]

Later in his book, Ranney anticipated how this well-developed system of thought control might begin to unravel under the threat of a fascist movement. The potential for such a movement would be characterized by the following:

- Situated in context of new world disorder

- Total rejection of the current system

- Right-wing and conservative labels are not helpful

- Mass popular movement composed of a number of different classes

- Unification around notions of “superior people” and “living space”

- Exclusion of “inferior peoples”

- Mobilization around some imagined glorious past

- Order and discipline imposed by a powerful leader

- Belief in the use of violence by armed forces and police.[3]

Ranney commented:

Today’s crisis is a toxic stew that leaves society susceptible to fascist movements. That stew includes: paralysis of both capitalist private enterprise and governments; the inability of the new world disorder to generate enough value to keep the global system going; and an inability of the system to even sustain the people who live in it. These elements could breed a fascist movement capable of overthrowing and replacing the new world disorder. Increasingly, there are masses of unemployed and disaffected peoples around the world who will find considerable appeal in finding their identity as a part of a “special people” who need “living space,” and a life grounded in some glorious if mythical past.[4]

It’s not as if we shouldn’t have seen something like this coming; there have been rehearsals of it for many years. I’d suggest that all of the candidates below were precursors, of sorts, of the Sanders and Trump phenomena of 2016:

1964—Barry Goldwater;

1968—Richard Nixon, George Wallace & Curtis LeMay, Peace & Freedom;

1980—Ronald Reagan, David Koch running for VP on the Libertarian Party line;

1988—Pat Robertson, Ron Paul;

1990—David Duke running for US Senator from Louisiana;

1991—David Duke running for Governor of Louisiana;

1992—Pat Buchanan, Ross Perot;

1996—Ralph Nader, Pat Buchanan, Ross Perot;

2000—Ralph Nader, Donald Trump & Pat Buchanan (Reform Party);

2004—Ralph Nader, Howard Dean, Dennis Kucinich;

2008—Ralph Nader, Dennis Kucinich, Ron Paul;

2012—Ron Paul, Herman Cain.[5]

Looking back at this list, I’d note that the right-wing sparks and spurts have been of much greater consequence than the “left” variants. And, of course, the rise of the Tea Party movement gave clear evidence of something different brewing on the right. But before the Tea Party, and perhaps more significant than the Tea Party, were Pat Buchanan and David Duke.

In 1992, Buchanan ran in the Republican primaries against the sitting president, George H.W. Bush, and won 3 million votes. His platform included restrictions on immigration (and building a border fence) and opposition to abortion and gay rights. Buchanan eventually supported Bush but he used his appearance at the Republican Convention to give what came to be called the “culture war speech.” For him and for many of his supporters, there was “a religious war going on in our country for the soul of America.” On the other side of that war were the Clintons:

The agenda Clinton & Clinton would impose on America—abortion on demand, a litmus test for the Supreme Court, homosexual rights, discrimination against religious schools, women in combat units—that’s change, all right. But it is not the kind of change America needs. It is not the kind of change America wants. And it is not the kind of change we can abide in a nation we still call God’s country.

Like Trump, Buchanan thoroughly enjoyed making fun at the expense of the Democrats. Here’s an especially memorable line:

Like many of you last month, I watched that giant masquerade ball at Madison Square Garden—where 20,000 radicals and liberals came dressed up as moderates and centrists—in the greatest single exhibition of cross-dressing in American political history.

But what galvanized the Buchanan supporters was his fervent opposition to trade. Not long before, he had been a regular garden-variety free trader. But, and I think this is a real but, he saw the devastation being left behind by the abandonment of American industries (especially in the cities), and he seized upon it like a dog upon a bone. His nostalgia for a lost America is, I think, genuine and blinded—black folks never appear in his remembrance of things past; only the hard-working white folks count. But, and this is another real but, his version of what has been destroyed and lost needs to be reckoned with. We’ll get back to Buchanan in a moment when he makes another appearance on the electoral stage in 2000.

For the moment, though, let’s turn to David Duke—who believes he has been given a new lease on life by the success of the Trump campaign thus far; in 2016, he’s now running for Senator from Louisiana. His earlier efforts to win high-level offices (in 1990 and 1991) were beaten back only through an intense mobilization of those who opposed him but revealed the extent of support he had among white voters—at least in Louisiana. Leonard Zeskind of the Institute for Research on Education and Human Rights has described Duke this way:

David Duke has been an ideological national socialist all his adult life. (Remember that the real name of Hitler’s Nazis was the National Socialist German Workers Party.) Before he became a Klansman, he was a junior national socialist, even marching around the LSU campus wearing a brownshirt uniform with a swastika armband once. His Klan…was a “nazi” Klan. He quit his Klan in 1980 and it has been 36 years since David Duke was a Ku Klux Klan member.

….

Mr. Duke is no longer the premier white nationalist movement leader that he once was. Others have emerged to push him into the second-tier ranks. It is a mistake, however, to discount his campaign. In this year of the “angry white male,” a significant stratum of white voters could be available if he asks for it. With 24 candidates in the primary, Mr. Duke needs a relatively small number of voters to push him into the run-off.[6]

Of special importance in this sorry tale is the brief entry of none other than Donald Trump into the primary process of the Reform Party in 1999―2000. The Reform Party was the odd child of Ross Perot’s third party campaign in 1996. By 1999, the party had splintered and, after a long song and dance, there were two possible candidates—Trump and Pat Buchanan (again!). A decade and a half ago, Trump’s powers of political perception were much greater than now and he called Buchanan out for being an anti-Semite and an admirer of Hitler. Truth be known, the Reform Party of that year was a strange creature. Trump kind of got it right when he said: “The Reform Party now includes a Klansman, Mr. Duke, a neo-Nazi, Mr. Buchanan, and a communist, Ms. Fulani.”[7]

Also worth noting in historical perspective is the sustained popularity of right-wing talk radio hosts (like Hannity, Limbaugh, Levin and—hard as it is to believe—the even more repulsive Michael Savage), Fox News and an array of social media news outlets (such as the Drudge Report established in 1995 and Breitbart established in 2007), the continued popularity of opinion makers like Pat Buchanan and Ann Coulter, the arrival of the conspiracy right (exemplified by Alex Jones’s infowars), and so on. My point is that the Trump moment is and continues to be the emergent result of a whole bunch of internally contradictory projects. But, we need to appreciate that they were all political projects—efforts intended to change the way that people thought and acted.

Ironically, perhaps no one can take more satisfaction with how things have worked out than Pat Buchanan—as was headlined in a recent op-ed, “Trump Stole My Playbook.” This turn of events reminds me of the fate of what were called the “anti-Semitic” parties that arose in Germany in the 1870s and gathered considerable support. Their electoral successes were short-lived and they all but disappeared as distinct organizations. At the time, some commentators thought that their views were little more than a brief hallucination. But it was no hallucination. The parties disappeared because there was no longer any need for them by the turn of the century—their views on the Jews had become all but completely accepted by all of the organized political parties, including the leaders of the Social Democrats (with the noteworthy exception of Rosa Luxemburg).[8] The proof of this powerful cultural absorption into the core assumptions of German political culture of what had been a political heresy, if not joke, was the relative ease with which the Nazis’ anti-Semitism became widely accepted after World War I. As I’ll get to below, there’s an even more dangerous version of Buchanan waiting in the wings of the Trump campaign today.

While it makes some sense to link the Trump and Sanders phenomena as a way of estimating the extent of the electoral upheavals in 2016, the differences between their respective campaigns deserve attention. Perhaps most important is the very different relationship between each candidate and his bases of support. While both candidates tapped into what had been a not quite visible level of deep discontent with politics as usual, their campaign activities had little in common. What Sanders more or less did was to put forward a set of rallying cries around a set of progressive measures (progressive especially in comparison to what Clinton was saying through much of the primary season) and enlist supporters in relatively traditional activities—contributing money, attending enthusiastic, but orderly, rallies and serving as campaign workers (making phone calls, knocking on doors, leafleting prospective voters).

On Trump and His Supporters

It was quite different with Trump—for all practical purposes, there has been only one activity for Trump supporters, apart from voting—attending rallies, rallies which often enough could as well be understood as white mobs. See, for example, the video of scenes from a number of different Trump events across the country posted on the web page of The New York Times in early August of 2016.[9] Hard as it is to believe, it seems evident that Trump’s rhetoric from the stage is at times quite tame in comparison to that of some of his supporters. There is more than a little about mob behavior that’s evident among some Trump supporters.

Mobs have loomed large in the ways in which white folks have come together to deprive blacks of their freedom and rights—the nightriders after the Civil War, the lynch mobs of the Jim Crow era, the attackers of students attempting to desegregate high schools in the 1950s and 1960s. During the Civil War, Karl Marx had noted “the abject character” of the poor whites and that characterization proved true long after the war was done.

But lest we miss something important, while the attractions of the mob have won out far too often, there were exceptions. By way of example, the recently released movie titled The Free State of Jones shines light on an all but completely forgotten moment during the United States Civil War—when miserably poor whites in Mississippi made common cause with runaway slaves to defy the Confederate and Northern powers and began to build a free state.[10] What in the world happened? I’m not going to answer the question. Watch the movie, and maybe read the review I’ve referenced, and then we can talk. I will say that while people are seldom talked into changing their minds, new circumstances can create new possibilities. In that context, it would be very helpful to develop ways of thinking that can become practical truths that drive what people might do—given the right set of circumstances.[11]

We need to appreciate the complexity of the support for Trump so we can avoid rather simple-minded notions that what we have to do, for example, is to “Stop hate!” Over the last couple of months, I have read plausible accounts of the characteristics of Trump supporters that are all but completely contradictory. His supporters are, variously, mostly people out for the entertainment value of a spectacular event; people who have seen their towns and small cities all but disappear as companies left; people who see no place for themselves, ever, in the world around them; and men who still aspire to the Hugh Hefner Playboy life style and are stuck with what they consider to be a bad substitute. I’m sure that there are other equally useful and limited characterizations.

I suggest that we assume that they’re all right. Each captures a slice of the complex composition of the Trump alliance. It would be helpful to get to some understanding of what holds them all together. Tentatively, and not so terribly originally (not surprising in a year when there are dozens, if not hundreds, of Trump interpretations offered everyday in newspapers and on cable TV), I’d argue that his supporters are:

- worried about the security of their relative well-being because they don’t have the credentials or family connections that would allow them to survive another 2008 meltdown of the economy;

- worried about their own personal and family safety because of a steady diet of warnings about terrorist threats (see, for example, this security-system TV ad) and deep-seated fears of the dangers posed by real or imagined criminal elements;

- inclined to be very respectful of the authority and authoritative views of law enforcement personnel of all sorts (if they are not law enforcement officers themselves or family members of those officers);[12]

- significantly influenced by the sense-making of right-wing talk radio, web-based news media and Fox News;

- in the case of the men, more than a little bit influenced by a notion that “we’re not going to allow them to kick us around any more.”

But at the end of all that, they still come in many different flavors—some will vote for the remnants of a conservative platform that Trump barely espouses (Paul Ryan kinds of people); some feel that they have no choice in light of a Hillary Clinton campaign that all but completely represents the continuation of business as usual; many are really angry about what has been going on and want someone to do something to stop it; some are convinced that the blacks “are getting everything,” and some are self-conscious reactionary revolutionaries.[13]

There may be others still.

There seems to be little evidence that Trump’s supporters are overwhelmingly people who have been victimized by industrial downsizing (although they exist).[14] There may very well be people who think that they should be doing better than they are—as do most of us. There also seems to be a lot of evidence that he has many more men backing him than women and that is a fact worth reckoning with.[15] And then, most important of all, there are the whites—cutting across virtually every other category of support for Trump. If nothing else, Trump is a white movement—notwithstanding his small assortment of black supporters.[16]

In the background of the Trump campaign, there are two developments related to the white character of his campaign worth recognition for the dangers they portend. On the one hand, there is the coalescence of a fairly broad variety of white nationalist leaders who have made common cause in their support of the Trump campaign. A main vehicle for that coalescence is the American Freedom Party. Its very up to date web page includes articles by a who’s who of white nationalists and re-postings of columns by Pat Buchanan and Ann Coulter. At the same time, The Occidental Observer, a white nationalist intellectual site edited by Kevin McDonald, a retired professor from the California State University system, has emerged as a significant source of analysis of the influence of white nationalists on the Trump campaign and on the development of a self-conscious strategy to see beyond the election.

At the end of August, Clinton delivered a harsh attack on the involvement of the alt-right in Trump’s campaign; she didn’t go very far. Specifically, she completely left out any explanation for why it was that “fringe elements” were gaining a growing audience. She did not acknowledge the possibility or likelihood that steadily worsening material conditions, and the threats they appear to pose to lots of people, might have anything to do with the development of far-right movements. It’s not surprising since, after all is said and done, the economic policies advanced by Clinton I, Obama, or Clinton II are more or less the same—advance the advanced economy (meaning technology plus finance) and figure out how to control the rest (by carrot or stick). By way of comparison, Trump’s policies promise a return of good jobs for the millions of ordinary folks who can’t really touch high-paying job sectors.

Truth be known, neither Clinton nor Trump will be able to do terribly much to affect where investment capital goes or who will benefit. They can grease some wheels rather than other ones but they will not get to pick the wheels. On the other hand, either one of them will have a great deal of political and military power—power that is more or less awful for the people of the world. Those on the left who are enamored with Clinton’s more polished explanation of how she would wield that power, as opposed to Trump’s blundering, will all but certainly be terribly disappointed (but maybe not) with what she will do. She, like Obama, will launch murderous drone attacks across the global war-scape and continue his all too willing arming of Israel and other supposed allies in the Middle East. The results will very well be more Gaza’s and Syria’s, more deaths, more maimed children, and more refugees (who, like the European Jews of the late 1930s and 1940s, will search the world for places that will let them in).

More importantly, Clinton’s approach is opposed to an insurgency from the left as much as it is to one from the right. It is our terrible failing that, by way of comparison, we on the radical left pose no threat at all and we don’t even merit a mention in her attack. For too long, the mainstream left has been preoccupied with making its politics agreeable—with virtually no real uptake—until the Sanders campaign. Meanwhile, a radical left has barely existed outside of the sectarian groups that use a vocabulary that is all but meaningless for most ordinary people (for examples across the sectarian spectrum, see the Spartacist League, the Revolutionary Communist Party, and endnotes, or is understandable only when it effectively represents a betrayal of principle (see, for example, the International Socialist Organization (ISO)).[17]

Through all this, there has been both deep continuity and substantial change on the right. It may be that the changes (around matters such as defense of homosexual rights against Islamic attacks) have made the realization of aspects of the continuity (such as the establishment of the legitimacy of a European or “white” people with legitimate group rights within the US) more politically feasible.

In spite of the crazy ups and downs of the Trump campaign thus far (end of September), I think that it’s possible, and maybe even likely, that a crystallization of Trump’s messages might still be articulated and will meet with a positive response (especially in the context of the ongoing miseries of the Clinton campaign, grounded, as they are, on the essential truth of the matter—that Hillary and those she represents benefit from virtually every aspect of the current state of affairs and want to maintain it, while pretending otherwise). The headlines of Trump’s messages would be:

- Unfair trade is ruining America

- Uncontrolled immigration is also ruining America

- Terrorism is a danger that must be obliterated

- Law and order must be preserved

- America is weak

- America is over-engaged overseas

- The political and media elites control the country

- Those elites rely on hypocrisy and corruption for their continued power.

And truth be known, as a friend pointed out, there is a small spot in the back of all of our revolutionary brains that wants Trump to win—in part because he makes mincemeat of all those who defend the “consensuses” that result in:

- trillions of dollars wasted on wars, in thousands of members of the American armed forces dead and many more wounded—including those who wind up in TV ads for the “Wounded Warrior Project” scam[18] or as props for politicians seeking votes by insisting on how much they care about Veterans’ Administrations hospitals—and, worst by far, in many hundreds of thousands of people from other countries who have been killed or maimed and millions more forced into fleeing from the killing fields that their countries have become during more than thirty years of continuous war;

- the inevitable elimination of jobs and the destruction of communities, small and large, by the all powerful movement of the markets and the inevitable forward march of technological innovation (made tangible by containerization and robotization).

On Sanders and, by Way of Contrast, Rosa Luxemburg’s Opposition to “War as Such”

The Sanders phenomenon clearly represents something much more hopeful. More than twelve million votes for someone prepared to be identified as a socialist in a one-on-one against arguably the most powerful Democratic Party politician in recent times hint at the possibility of a mass socialist movement that might overcome capitalism. Needless to say, changing votes into mass political activity beyond voting will be no easy task.

At the same time, the fairly obvious weaknesses of the Sanders campaign when it comes to US world domination and military engagements pose additional obstacles to the transformation of the genuine accomplishments of the Sanders moment into something that goes beyond it. To be more precise about this matter, it is more or less obvious why Sanders steered his campaign the way that he did (systematically avoiding any substantive engagement with the realities of the American empire); he wanted the votes of those who wouldn’t be willing to do the same. What’s less clear is the extent to which Sanders supporters themselves share their candidate’s reluctance. If they, like many more before them, are willing to embark on a “political revolution” that’s built upon the defense of the interests of American workers and the broader population at the expense of people around the world, their “revolution” will prove to be an empty one—one that will only harden the chains that keep people within the system that imprisons them.

In the wake of Sanders’s endorsement of Clinton and the months since (with Sanders’s quite limited participation in the Clinton campaign—either because of his preferences or, more likely, hers, as she “pivots,” in that memorable word from the 2016 campaign, to the right), it is not at all clear what will be left of that Sanders moment. The political organization intended to carry the Sanders movement forward, Our Revolution, appears to have gone off the rails before it got on them (read about the staff revolt within the new organization, and for an overly friendly criticism, see Michael Albert’s open letter).

What is clear is that the Clinton campaign is making every effort to consolidate the Democratic Party as the one real capitalist party—by which I mean a party with an unequivocal commitment to serving and preserving the national and global interests of the owners of capital and of the nation state that remains the most powerful guarantor of the existing state of affairs. (Those are the interests that she presumably addressed in her speeches to Goldman Sachs.) Let me be clear—this does not mean that Clinton will offer no programs designed to win the support and the votes of many millions of poor and working class people. In order to win and to rule, a central task of those seeking election to positions of great power remains the cultivation of the confidence and hopefulness of large numbers of those being ruled. In spite of the rightward turn of her campaign messages, Clinton will continue to make much of her support for a party platform that incorporates many of the demands of the Sanders campaign for various domestic reforms.

At the same time, though, she will be attempting to secure broad support for continued aggressive US military involvements across the globe—most importantly, in southwest Asia, the Middle East, North Africa, Eastern Europe and the Far East. These involvements pose a great danger of more prolonged and more explosive wars. This is the light within which we should view the celebratory patriotism of the Democratic Convention and especially the staging of the much-heralded speech of Khzir Khan attacking Trump’s anti-Muslim stances resulting in widespread applause for him and his wife as “Gold Star” parents (parents who have lost a son or daughter in combat)—both at the Convention and beyond it.[19]

The speech was orchestrated so well that it seemed inconceivable that Trump would not be cowed. Needless to say, he was not and he came up with ways of attacking the couple’s integrity. However, perhaps more significant than Trump’s own response was the curious response of Trump supporters to a mother of a current soldier who spoke at a campaign event for Mike Pence. They cheered when she said that she was a mother of a serving soldier but jeered when she challenged Pence to distance himself from Trump. This suggests that some Trump supporters retain a strong sense of affection for people in the armed forces and veterans but are not willing to allow that support to drag them into support for the military adventures launched by the country’s political and military leaders. The John McCain option of unqualified support for the warriors and the wars may be becoming obsolete among a population that was long assumed to be endlessly available for both purposes.

All this confirms the need for a consistent anti-war and anti―world domination position as an essential element of a challenge to Clinton and the Democrats. There was an encouraging moment at the Democratic Convention when chants of “No more war!” erupted from Sanders supporters during the speech of Leon Panetta (the former Director of the CIA and Secretary of Defense), where he was praising Hillary’s determination and willingness to pursue military options.

In 2015, the United States deployed its military forces in at least 135 countries—ranging from specific targeted missions to long-term engagements. Recently, the Pentagon confirmed that the United States had 662 military bases of one kind or another in 38 nations (a good number of them encircling what are at times portrayed to be its most serious adversaries—Russia, China and Iran). Its warships and warplanes patrol the oceans and the skies and add emphasis to the warnings that are embedded in its military bases. It is a monstrous force, bearing comparison with one or another of the great armed nations in George Orwell’s 1984 or, perhaps of greater relevance to an audience in 2016, the empire in the Star Wars movies. The only defensible thing to do is to tear it down and make it impossible for it to be built again anywhere. But alas, many will say that such a move will enable some really bad folks to take advantage. Truth be known, none of us should be inclined to think that a defense of the Russian, Chinese or Iranian regimes is a good starting place for thinking about how to fight against the United States military monster. We have an unusual claim to make and we challenge those who dismiss it to make a better one.[20]

What’s needed is not “America First!,” but rather international solidarity with all of those who are exploited or oppressed by the current state of affairs. A writer at the Tampa Bay Communist League has brought the wisdom of Rosa Luxemburg to our attention:

Rosa Luxemburg, three times a minority as a Jewish-Polish woman in Germany, rose to international prominence by issuing the definitive Marxist statement regarding the war [World War I] from prison:

This war’s most important lesson for the policy of the proletariat is the unassailable fact that it cannot parrot the slogan Victory or Defeat, not in Germany or in France, not in England or in Russia. Only from the standpoint of imperialism does this slogan have any real content. For every Great Power it is identical to the question of gain or loss of political standing, of annexations, colonies, and military predominance. From the standpoint of class for the European proletariat as a whole the victory and defeat of any of the warring camps is equally disastrous.

It is war as such, no matter how it ends militarily, that signifies the greatest defeat for Europe’s proletariat. It is only the overcoming of war and the speediest possible enforcement of peace by the international militancy of the proletariat that can bring victory to the workers’ cause. …Proletarian policy knows no retreat; it can only struggle forward. It must always go beyond the existing and the newly created. In this sense alone, it is legitimate for the proletariat to confront both camps of imperialists in the world war with a policy of its own.

…But to push ahead to the victory of socialism we need a strong, activist, educated proletariat, and masses whose power lies in intellectual culture as well as numbers. These masses are being decimated by the world war. …The fruits of decades of sacrifice and the efforts of generations are destroyed in a few weeks. The key troops of the international proletariat are torn up by the roots.

…This blood-letting threatens to bleed the European workers’ movement to death. Another such world war and the outlook for socialism will be buried beneath the rubble heaped up by imperialist barbarism. …This is an assault, not on the bourgeois culture of the past, but on the socialist culture of the future, a lethal blow against that force which carries the future of humanity within itself and which alone can bear the precious treasures of the past into a better society. Here capitalism lays bear its death’s head; here it betrays the fact that its historical rationale is used up; its continued domination is no longer reconcilable to the progress of humanity.

The world war today is demonstrably not only murder on a grand scale; it is also suicide of the working classes of Europe. The soldiers of socialism, the proletarians of England, France, Germany, Russia, and Belgium have for months been killing one another at the behest of capital. They are driving the cold steel of murder into each other’s hearts. Locked in the embrace of death, they tumble into a common grave.

We need to stop comparing Bernie Sanders to Hillary Clinton. Instead, we need to compare him and ourselves to revolutionaries like Rosa Luxemburg or, closer to home, Wendell Phillips. At the same time, we need to recall and reclaim a mostly lost legacy of class struggle as the road to world peace:

The political meaning of the concept of exploitation is the most radical denial of capitalist legitimacy. This forced the workers’ movement to adopt internationalism as its main political doctrine which—in modern conditions—is also a denial of institutionalized political power (the nation-state) as well as a rejection of property and of the (patriarchal) family. It tends to be forgotten, but it was quite clear to everybody around 1900 that internationalism was a radicalization of the idea of perpetual peace, as it tends to be forgotten, too, that perpetual peace was a revolutionary idea. The official teaching was that civil war (revolution) was illegitimate, but war legitimate. Socialism had taught the opposite of that. Global class struggle would create perpetual peace, as the agent of war (the supreme coercion), the state, will be dead. Even today, if there would be tens of millions of people believing this, the powers-that-be would be frightened. One needs to have a little historical imagination to picture how this kind of “godless communism” affected those stable, conservative, puritanical, diligent, respectful, hat-raising societies of the late nineteenth century.[21]

Resemblances to the Past

In recent discussions, Loren Goldner has suggested that the period we are entering might resemble the early 1960s—exemplified by the interconnection between the Southern Civil Rights movement and the nascent New Left. I suggested, a bit differently, that a comparison might be made with the moment after the election of Lyndon Johnson in 1964 and the almost immediate escalation of the war in Vietnam—leading dramatically and, incredibly quickly, to an explosive growth in the numbers of people in SDS and other groups and to their radicalization (including a break with the Democratic Party and, more broadly, with an orientation to electoral politics).

We synthesized our views in a recent Insurgent Notes editorial:

The current period reminds us, in a bizarre way and in much more dire circumstances, of the early 1960s. Then as now, an idealistic new generation was awakening to politics. Then as now, in both the nascent New Left and early civil rights movement (both deeply interconnected in the Jim Crow South) and today after Occupy and Black Lives Matter, something got out of the bottle that will not easily be put back in. We insist above all, where the potential role of our marginal milieu as conscious communists is concerned, that small groups do not shape consciousness, events do. Events for the 1960s were the later years of the southern civil rights movement, the war in Vietnam, the radicalization of black people after the civil rights movement hit a wall, and the rank-and-file and wildcat upsurge in the United States working class. By the late 1960s, some many thousands of young people coming out of the New Left and the Black Liberation Movement had declared for revolution, and many joined groups organizing for it. It did not end well, for reasons that we cannot do justice to here.[22] For the most part, the emerging revolutionary movement was dominated by either Stalinist/Maoist/Trotskyist sects or by groups well on the way to embracing an all-purpose, and hardly anti-capitalist, “progressive” politics. A not insignificant part of the black left turned towards nationalism. And a small part of what might be considered the middle-class white left was drawn into the substitution of terrorist violence for politics. Little of consequence is left of all of it although, to be fair, Sanders’s current vision has more than a little in common with the above-cited progressive politics.

Let me be explicit. What was missing as the 1960s ended was a substantial and self-conscious revolutionary and emancipatory bloc that rejected Leninism-Stalinism-Trotskyism-Maoism. What might have provided the basis for such a bloc was a new synthesis of libertarian communism (opposed to all of the miseries of supposed socialism in the Soviet Union and its copycats in places like eastern Europe, China, North Korea and Cuba and grounded in a “new reading” of the works of Karl Marx) and anarchism. The remnants of the earlier small groups that might have provided the basis for the development of such a bloc were not ready for the challenge. I’m thinking of groups such as the Johnson-Forest Tendency, News and Letters, Root and Branch, the people around Murray Bookchin, the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, etc. It didn’t help much that individuals in these groups were inclined to spend more time competing with each other than seeking common ground with those in other groups.[23]

As I look back at the period, what seems evident is that the turn to the working class by a good number of ex-student radicals as the potential driver of revolution was not accompanied by an equally serious turn to the work needed to understand exactly what capitalism was up to. By way of a small personal recollection, when the study groups of the Taxi Rank & File Coalition, that I was active in for the better part of the 1970s, were initiated in the early 1970s, the readings of Marx were almost entirely limited to Value, Price and Profit and selected excerpts from some of his other works. Recently, I have come to realize that Value, Price and Profit was a better work than I thought at the time but it remains the case that the engagement with Marx was quite limited for many genuine radicals (see more about my re-reading below).

Keep in mind that, at the time, the Monthly Review folks were quite hegemonic in advancing their Marxism for modern times and the Maoist Guardian newspaper was arguably the most influential voice of supposed revolutionary politics. But it was not completely dreary—this was also a time when Radical America, Liberation, New Left Review, Race and Class, the first New Politics, as well as perhaps hundreds of local radical newspapers, supported by a remarkable national news service (Liberation News Service), provided some balance and alternative interpretations.

To back up a bit, in 1968, with the war in Viet Nam raging and, unlike now, scenes of dying US soldiers and Vietnamese soldiers and civilians filling the TV screens night after night, the energy of great numbers of young people was drawn into the campaigns of the peace candidate, Eugene McCarthy, and a bit later, Robert Kennedy. (I should know—I was one of them and think I might even be able to dig out the articles I wrote for my college newspaper about why). What I want to emphasize is the very uneven and relatively long-term processes of radicalization that were in play even in the context of a quite explosive historical context. I think it’s likely that the same pattern will be evident now—although the background context of profound world economic crisis and increasingly murderous conflicts across the globe, as compared to a somewhat localized imperialist war, could make a difference.

Therefore, I suggest that we take a longer look from the mid-1950s emergence of the Civil Rights movement in the 1955 Montgomery Bus Boycott (and perhaps even earlier) up until the late ’60s/early to mid-’70s, to try to imagine/understand how radical/revolutionary movements might emerge and, more important, how they might avoid the fates of the movements of the ’60s. I have been reading what I think is a pretty good book by Howard Brick and Christopher Phelps titled Radicals in America: The US Left Since the Second World War. It provides a comprehensive and quite detailed account of the multiple layers of activity that characterized sixty plus years of American radicalism. It documents what was an extraordinary range of forms of activism—journals, arts, protests, found and lost causes of all sorts—and highlights the ways in which continuities mattered even when they were not at all obvious at the time.

To balance out this account, let me note two other developments. First, in the halls of the universities, there was a serious turn to Marx—a turn all but completely divorced from practical radical politics. By way of example, read Moishe Postone’s accounts of what he and his friends did at the University of Chicago at the end of the ’60s.[24] Their approach might be summarized as: “Read critically and vote for the liberal Democrats!” Their serious engagement with Marx was squandered by their refusal to think or act politically.[25]

Second, as has been noted often enough, the Civil Rights movement had given rise to the student, anti-war and black liberation movements and, in turn, to the emergence of women’s liberation and gay liberation movements and had a deep and broad influence on music and popular culture. In other words, something quite significant had occurred because of the impulse of a black freedom movement.[26] It remains to be seen if the contemporary black freedom movement has the same potential. For a hopeful view, see Jim Murray’s blog on Hard Crackers. What deserves more attention than it has received is the significant number of so-called “white folks” in the protests against police violence. In recent days, this has been especially noticeable in the protests that erupted in the South—Baton Rouge and Charlotte—places where all but no white folks joined in the Civil Rights movements of the 1950s and 1960s.

In the backdrop of all this is what might be considered the domestication of the left that was left behind by the ’60s. Part of that domestication was the result of what David Graeber has termed a “grand bargain” wherein ex-radicals were granted significant autonomy within their professional niches, especially the academy, substantial material benefits (including early entry into the developing gentry economy in the context of re-shaped urban environments and consistently appreciating real estate values), and an inside track of sorts when it came to the education of their children into the next generation of those who could afford to be altruistic.[27]

The Almost Fifty Years’ Assault Against the Working Class

The emergence of this new stratum was soon accompanied by a devastating attack on the American working class. Each year since has witnessed advancement for the one sector and retrogression for the other. I enumerated some aspects of the retrogression in my first Insurgent Notes education article (“Rethinking Educational Failure and reimagining an Educational Future”) in May 2011:

Canary in a Coal Mine

Let me begin with the big picture. In an illuminating book, Global Decisions, Local Collisions, Dave Ranney has examined the fairly devastating impacts of the collapse of manufacturing in Chicago starting at the end of the 1970s:

In the late 1970s, I lived and worked in Southeast Chicago. At the time, the neighborhood was a vibrant, mixed-race, working class community of solid single-family homes and manicured lawns. Its economic anchor was the steel industry. US Steel Southworks, Wisconsin Steel, Republic Steel and Acme Steel employed over 25,000 workers. Southeast Chicago was also teeming with businesses that used steel or that sold products to the steel mills: steel fabrication shops, industrial machinery factories, plants that made farm equipment, and railroad cars. There were also firms that sold the mills industrial gloves, shoes, tools, nuts and bolts and welding equipment. The commercial strip had retail stores, bars and restaurants. Many of these, like the steel mills, were open twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week.

……

During the 1980s, the Chicago steel industry collapsed and took down with it much of the related industrial and service economy that depended on it. Both Wisconsin Steel and US Southworks eventually closed. Republic Steel was bought out by a conglomerate and was greatly downsized. Steel jobs in Southeast Chicago declined from about 25,000 workers to less than 5,000 in a decade. And the decline in manufacturing extended far beyond steel. The Chicago metropolitan area suffered a net loss of 150,000 manufacturing jobs during the 1980s. People’s lives were torn asunder in the wake of massive layoffs. Divorces, alcoholism, even suicides were on the rise. Industrial unions were decimated and union membership declined throughout the United States. The new jobs created in the wake of this decline paid far less than the jobs that had been lost. Many were temporary or part-time and usually lacked benefits like health care. Workers taking these jobs no longer made enough to live on. So they worked two or sometimes three jobs to make what they had previously made at one. Many of the dislocated workers never worked again. The struggle over civil rights in the workplace and within the union was over because the workplace itself no longer existed.[28]

Although Ranney modulates his nostalgia for Chicago’s lost world by acknowledging the historical significance of racial discrimination (that resulted in constricted job opportunities and lower wages for Hispanics and African-Americans) and the struggles against those discriminatory practices in workplaces and unions, he suggests that something very important had been lost:

Not only were the community and its economy vibrant, there was a system in place that looked to future generations. The mills and many of the related firms had strong unions. Through the union you could get your children into the steel mills to learn a trade or get a well-paying job that would allow them to save and go on to college.

In passing, I’d suggest that this notion of a link to the future is a very important one and that its frequent absence in contemporary life, as a result of the devastation visited upon the productive workforce and the long painful decline in working class living standards, has a good deal to do with what I interpret as a withdrawal from both intellectual and political engagement on the part of many. At the same time, as evidenced by the recent events in Northern Africa and the Middle East, the return of people who thought that they had no future to the stage of history should not be discounted.

Fast forward to the middle of the 1990s and listen to the words of Ms. Sparks, a sixth-grade teacher who had grown up in Chicago, in all likelihood in the same neighborhood that Ranney described, and had returned to teach in the elementary school she had attended:

I am from streets with buildings

that used to look pretty.

From safe walking trips to

Mr. Ivan’s family grocery store,

where now stands a criminal sanctuary.

I am from a home and a garage

Illustrated with crowns, diamonds,

upside-down pitchforks, squiggly

names and death threats.

I am from a once busy, prosperous

and productive community;

where the fathers and mothers

earned a living at the steel mills,

And the children played

Kick the Can and Hide and Go Seek

Until they could play no more.

I am from here.

[reprinted from Organizing Schools for Improvement: Lessons from Chicago]

The destruction of the world that Ranney and Ms. Sparks remember and its consequences have not received the attention they deserved. Indeed, it seems like we have simultaneously managed to lose the past and the future.

The wave of Chicago factory closings was a canary in the coalmine moment.[29] It signaled the emergence of a new era in American (and world-wide) social and economic life—an era characterized by:

- factory closures and plant transfers to lower-waged locations;

- outsourcing;

- the development of finance as a major source of profits (even for industrial firms);

- the elimination of millions of jobs;

- a rise in part-time or temporary jobs as primary employment;

- the depopulation and physical destruction of cities (such as Detroit and Baltimore);

- gentrification in many urban neighborhoods and the rise in political importance of the social groups formed by that gentrification;

- severe decreases in unionization rates in the private sector;

- lowered wages and benefits in the private sector;

- extensive technical innovation in communication, transportation and production—resulting in still more job losses;

- the increasing commodification of the satisfaction of all sorts of human needs (such as care for the elderly and the very young and the maintenance of households) and an accompanying proliferation of low-waged, on or off-the-books, service jobs; and

- the establishment of credit (at either normal or usury rates) as an indispensable way of life for many members of the middle and working classes.

And perhaps, as a result of it all, it was characterized by the sucking out of the life blood of the collective spirit of the American working class.[30]

The losses are painful ones. Once again from the IN editorial:

Let’s emphasize that we are more than aware of the pain and suffering (in injuries, chronic illnesses and early death) experienced by workers in industries like steel, auto, rubber, mining, textiles and furniture manufacturing, and we have no interest in seeing the pain and suffering of reindustrialization imposed as the price of progress. Nonetheless, we are acutely aware of the ways in which concentrated industrial production made possible remarkable forms of camaraderie on the shop floor and, beyond the workplaces, the establishment of towns and small and large cities where working-class families were able to create communities that came quite close to the kinds of communities we might imagine desirable in a postcapitalist society—communities where forms of mutual support were all but universally present and opportunities for children to pursue expanded horizons were real rather than advertising slogans. We need a restoration of the advantages of industrial civilization of the last half of the twentieth century without the reimposition of the pain and suffering associated with it. For the moment, we’ll hold off on the matter of the deep satisfaction involved with cooperative labor in industrial production—other than to say that we imagine a return of that satisfaction at a higher level.[31]

These events were the foundation for the rise of the recently described “unneccessariat.” The advancement of the other professional sector is almost always understood as something separate and apart but the two developments need to be understood together as a fundamental structuring element of contemporary popular politics.

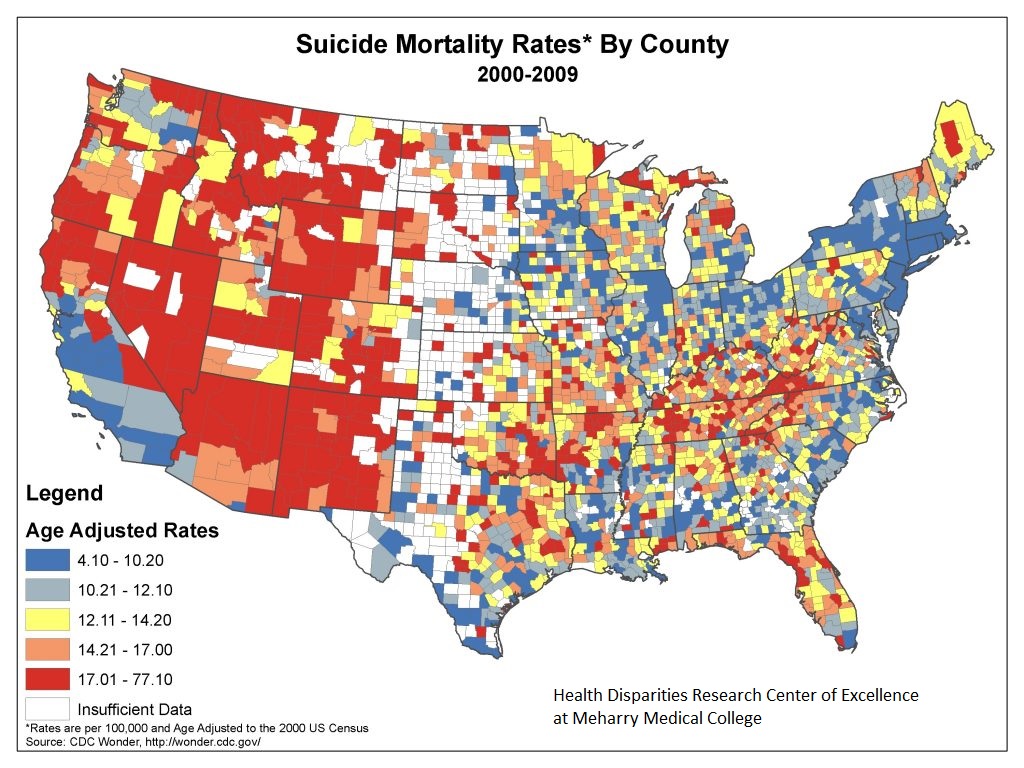

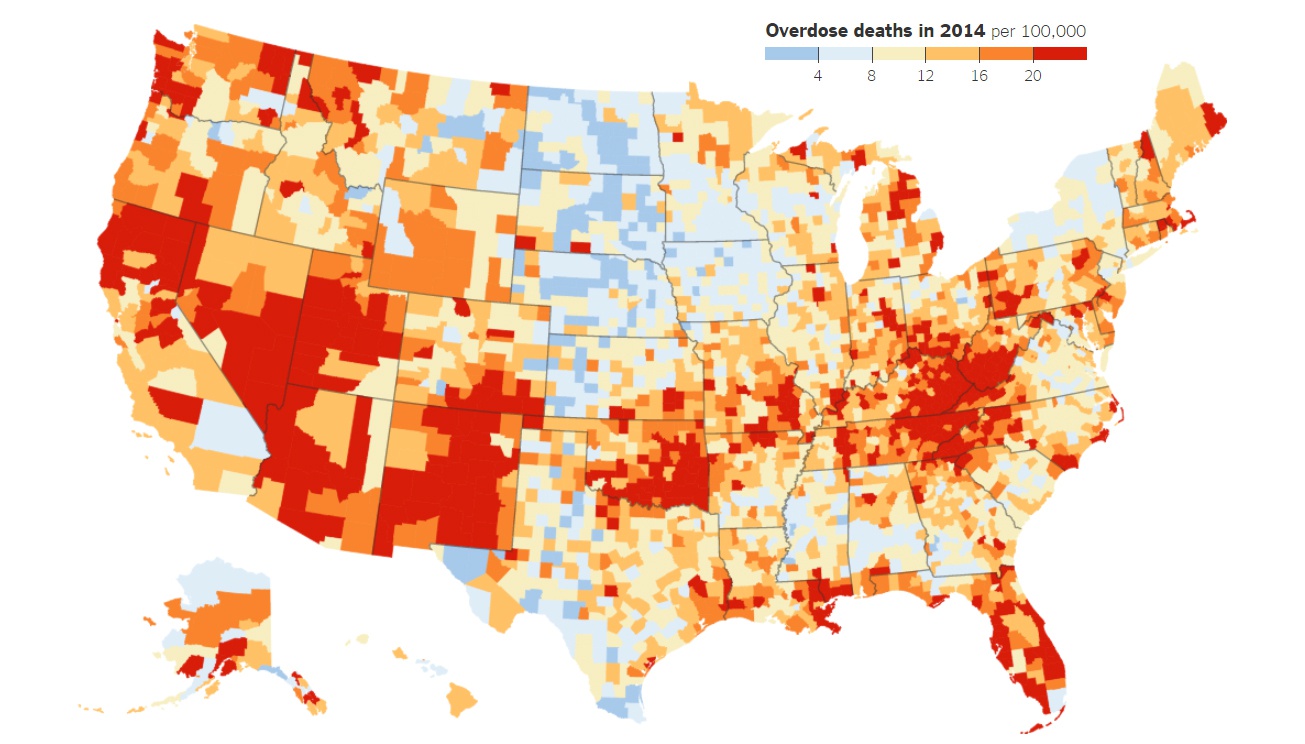

Let me note in passing the stark geographic character of the locations of the unnecessariat across the United States.

And also let me note the possibility of drawing other maps which would highlight the locations of the super-rich, very rich, rich and well-off populations in hyper-inflated metropolitan real estate markets (places like Boston, New York City and San Francisco). If we looked closer still, we could also observe the juxtaposition of urban populations facing displacement with those populations reaping the benefits. By way of illustration of what this looks like on the ground today, see the Guardian on gentrification in San Francisco and Los Angeles. The cruel worsening of life circumstances has occurred more or less simultaneously for almost all of the people who lived in many small and mid-sized towns and cities across rural America and a not insignificant number of larger cities (places like Baltimore, Detroit, Gary, and Newark), and for substantial numbers of people who lived in cities and the surrounding areas that presented a prosperous smile to the world (places like New York, Boston, Chicago, San Francisco and Seattle).

The Moment and a Response

At the current moment, what a revolutionary left is prepared and able to communicate to large numbers of people could make a difference—in the context of unresolved economic crisis and political upheaval—not only in the United States but around the world (more about that to come). As we think about how we might contribute to a substantial expansion of the capacities that a revolutionary left needs to do so, we would be well advised to avoid chasing after notions of close-at-hand ruptures[32] and, instead, to take sober measures of those forces that might be marshaled in support of an emancipatory breakthrough and the forces arrayed against the prospect of such a breakthrough.

On the other hand, the opposed forces include a state with almost unimaginable police and military resources, a not-yet-dead mainstream constellation of corporations, foundations, politicians, non-governmental organizations and a variety of media (at its most left version, think Rachel Maddow and Chris Hayes on MSNBC), and what might best be characterized as resurgent ethnic/racial nationalist movements. In the backdrop of these intentional forces, I’d make mention of an oftentimes passive and absent-minded population whose absent-mindedness is endlessly nourished by a dream world of perpetual ads, in every imaginable format, that cultivate a state of “stupefaction.”[33]

I’d supplement that quick characterization by borrowing an analysis from Leonard Zeskind, who argues that the vertices of the “three-way fight” among the politically engaged are the globalists, the nationalists and the internationalists. The first vertex is pretty much a world-wide project of the very wealthy and their accomplices in governments, corporations, financial institutions, commercial enterprises, think tanks, the academy and foundations. Those accomplices have few or no autonomous interests within the social bloc.

The nationalist vertex is distinguished by its cross-class composition and the clear inclusion of forces that have autonomous, if not antagonistic, interests. Examples of the nationalist vertex would include the various European far-right parties, a broad spectrum of Trump supporters in the United States, perhaps most of the “leave” voters in the Brexit referendum, and the “fascist” Islamists.[34]

On the internationalist vertex, there are four somewhat discrete forces:

- a small number of committed internationalists and anti-fascists;

- very well-meaning human rights activists who defend those without rights;

- “unvoiced” workers and others in the metropolitan countries and elsewhere who simply cannot imagine being against solidarity with their fellow human beings,[35] and

- very practical internationalist migrants and refugees who move their bodies and those of their kids across borders that otherwise seem so formidable.

Unfortunately, these constituencies have no coherent politics as compared to those of the globalists and the nationalists.

Our internationalist, anti-nationalist and anti-globalist engagements need to become much more integrated, explicit and activist. One obligation that we should embrace is the adoption of a comprehensive and long-term political strategy to break up the social blocs that constitute the working class grounded sub-groups of the nationalist movements. In that context, the re-articulation of class as fundamentally internationalist is central.

I’ll pick up the argument from there in the next part.

- [1]Let me say at the start that I don’t want to contribute to any notion that Donald Trump as a person should be taken seriously. He is a clown, apparently a rich one. He’s like another clown with orange hair—Clarabell. For those who are not old enough to remember, Clarabell was a character on the Howdy Doody show that was popular in the 1950s. It was a time when what was on TV was quite innocent by comparison with now. But clowns are clowns. Unfortunately, I was not the first person to think of the Clarabell comparison. On the other hand, I think the significance of his candidacy and popularity deserves the most serious consideration in light to the potentially terrible dangers they pose.↩

- [2]David Ranney, The New World Disorder: The Decline of US Power, p. 118.↩

- [3]Ibid., pp. 219―221.↩

- [4]Ibid., p. 222.↩

- [5]It’s worth keeping in mind that all of the national developments were accompanied by state and local level developments that reinforced or exaggerated the national ones.↩

- [6]See Leonard Zeskind, “David Duke Is More Than a Former Klansman,” August 2, 2016, Institute for Research and Education on Human Rights. In a similar manner, while not underestimating the significance of Trump’s primary victories, we should keep in mind that, almost until the end, his triumphs were the result of the distribution of opposition votes among numerous other candidates.↩

- [7]In spite of my appreciation for the cleverness of Trump’s dismissal, it’s important to note that Lenora Fulani was no “communist.” Fulani was a member of what can only be described as the cultish New Alliance Party that had joined the New York Independence Party (the New York State branch of the Reform Party) for its own reasons. For an analysis of the strange history of the New Alliance Party, see the Political Research Associates’ page.↩

- [8]See Lars Fischer, The Socialist Response to Anti-Semitism in Imperial Germany and Shulamit Volkov, Germans, Jews, and Antisemites: Trials in Emancipation.↩

- [9]I do not believe that the Times has ever before published or posted anything with language such as “Fuck Islam,” “Fuck the nigger,” or “Trump the bitch.”↩

- [10]There’s a really fine review of the movie by the Labor and Working-Class History Association. And a very moving song about the same events. I’d also recommend Dave Roediger’s recent book about the moment of almost unimaginable freedom that was the last part of the Civil War and the twelve years of Reconstruction, Seizing Freedom: Slave Emancipation and Liberty for All. Roediger emphasizes the ways in which the abolition of slavery by the United States Army’s command was often an acknowledgment of the practical abolition that had occurred on the ground when Union soldiers simply refused to treat runaway slaves as slaves and, instead, recognized them as fellow human beings. As a very wise revolutionary, Marty Glaberman, once wrote, changes in what people do often come before changes in what people think, let alone changes in what people say. See Martin Glaberman, Wartime Strikes: The Struggle Against the No-Strike Pledge In the UAW During World War II.↩

- [11]The history of American abolitionism, the movement to abolish slavery, is the premier example of this potential. See Noel Ignatiev’s Introduction to The Lesson of the Hour: Wendell Phillips on Abolition and Strategy. As Loren Goldner has recently pointed out to me, the characteristic that both Phillips and Rosa Luxemburg embodied was intransigence.↩

- [12]There is significant evidence of the ongoing autonomization of the police—by which I mean that the cops are not necessarily always doing the bidding of those in charge of the governments and departments they are employed by. This is most evident in the decades long history of police rebellions, most often galvanized by police unions, to challenge the authority of elected officials; for a recent example, consider the arrest strike in NYC in 2015. Although it’s hard to come by really accurate numbers, there are a lot of cops in the United States. See, for example, Daniel Bier’s “By The Numbers: How Many Cops Are There In the USA,” The Skeptical Libertarian, August 26, 2014, in which the author argues that there are over 1 million. He also points out that the rate of fatalities among police officers is quite low. In mid-September of 2016, the Fraternal Order of Police, with over 300,000 members nationally, formally endorsed Trump. When you add in family members and other relatives, let alone friends, neighbors and fellow residents of communities with relatively high numbers of police residents, you wind up with a sizeable group of people under the influence of the views of police officers. See my article on the events in Ferguson, Missouri.↩

- [13]It bears repetition that there are people on the far right who are as determined as some on the far left to overthrow the existing society and not simply to make it more conservative.↩

- [14]In May 2016, a New York Times article reported that Trump voters in the primaries up to that point had average family incomes of $72,000. See Nate Silver, “The Mythology of Trump’s ‘Working Class’ Support,” FiveThirtyEight, May 3, 2016.↩

- [15]See Donald Parkinson, “Reaction Today: Who Are the Alternative-Right and Do They Matter?” Communist League of Tampa for World Revolution, August 11, 2016.↩

- [16]Lest we lose sight of this important reality, it’s worth emphasizing that among today’s white folks are the children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren of people who were not considered white. In spite of all evidence to the contrary, “white” is not a biological category; it’s a historical-political one. It potentially includes all those who are not considered to be black. Unlike previous periods of US history, however, to be black, in and of itself, does not necessarily mean that one is subject to significant disadvantage. And to be white means less than ever that you’ll be spared some of life’s hardships. But, in spite of everything, whiteness endures. See John Garvey and Noel Ignatiev, “Beyond the Spectacle,” CounterPunch, June 22, 2015.↩

- [17]As has been said before, the ISO is a socialist organization that is pretending to be liberal that is pretending to be socialist. Its chameleon-like character is especially conducive to attracting new members.↩

- [18]See Fox News, “Wounded Warrior Project’s Top Execs Fired Amid Lavish Spending Scandal,” March 10, 2016.↩

- [19]For some additional insight into the complexity and ambiguity of the Khan family’s perspectives, see Ben Norton, “Khizr Khan: US Wars ‘Have Created a Chaos’ in Muslim-Majority Countries,” Salon, August 2, 2016.↩

- [20]There are still handfuls of people in the United States and around the world who believe that Russia is worthy of defense as a nation that continues to embody, in a more or less distorted form, the emancipatory potentials of the Russian Bolshevik Revolution of 1917. Although I recognize that the Bolshevik Revolution was carried on in the name of socialist revolution, I insist that it was nothing but a false start. Worse still, it quickly became a monstrous tyranny, arguably worse than anything other than the Nazi death machine, that poisoned the seeds of revolutionary opposition to capitalism for almost a hundred years.↩

- [21]GM Tamas, “Ethnicism After Nationalism: The Roots of the New European Right,” Socialist Register, 2016.↩

- [22]See below for a bit more of an analysis.↩

- [23]I would not want to underestimate the difficulties involved in such a cross-group approach. In the early 1980s, I helped organize a No Easy Answers Left conference in New York City that was an attempt to bring together people from a wide variety of groups and perspectives who the organizers thought should have good reasons to be connected with each other. Very little came of it. For a brief account, see Michael Staudenmaier, Truth and Revolution.↩

- [24]Postone is the author of Time, Labor and Social Domination.↩

- [25]At the risk of being charged with partisanship (because of my connections with the group), I’d highlight the example of the Sojourner Truth Organization as a real alternative to the various dead-ends. See, for example, the Insurgent Notes Symposium on Truth and Revolution.↩

- [26]Much that happened confirmed the remarkably prescient views of CLR James in his 1948 report, “The Revolutionary Answer to the Negro Problem in the United States,” at the 13th convention of the Socialist Workers Party.↩

- [27]The recent debate on the City University of New York―Professional Staff Congress contract illuminates the consequences of this development—even within the academy. The contract improved the position of full-time faculty at the expense of part-time adjunct faculty. My guess is that no group voted more consistently in favor of the retrograde contract than the full-time “left” faculty.↩

- [28]David Ranney, Global Decisions, Local Collisions.↩

- [29]An allusion to caged canaries (birds) that miners would carry down into the mine tunnels with them. If dangerous gases such as carbon monoxide collected in the mine, the gases would kill the canary before killing the miners, thus providing a warning to exit the tunnels immediately.↩

- [30]For an updated view of Ranney’s perceptive understanding of the nature of the current capitalist crisis, see his previously cited New World Disorder.↩

- [31]Lest we be mistaken, the same kinds of developments occurred across Western Europe and parts of South America.↩

- [32]See the section below on Guerilla Wars.↩

- [33]See Keston Sutherland, “What’s The Ugliest Part of Your Market-Researched Anaclitic Affect Repertoire?”↩

- [34]Here I am referring to the argument made by Alain Badiou in his speech of November 2016. Much more about that below.↩

- [35]I would recommend that we not jump to conclusions about the backwardness of the working class and, instead, to imagine that there are more than a few people who hold on to sentiments of freedom and solidarity, even when those commitments are not expressed in explicit terms. In that context, I’d cite Heinrich Haine’s recent article, “Notes From Non-Existence,” Mute, June 28, 2016, that highlighted the fact of significant majorities voting to “remain” in a number of predominantly working-class cities and neighborhoods across the United Kingdom.↩