In 2015, during an “Ideas for freedom” debate, English, Greek, and French comrades tried to answer the question “Is the far-right winning over Europe’s workers?” In response, I explained why and how the National Front could attract workers and their votes.[1] Now I would like to describe how the National Front consolidates its power, once it succeeds in winning municipal elections.

But maybe, before doing that, I should briefly recall that the National Front was created in 1972. At the beginning it was a federation of far-right grouplets, consisting of no more than 500 people, themselves divided into several tendencies, from the most reactionary Catholics to the pagan “national-revolutionaries,” from former pro-Nazi collaborators to racist former French settlers in Algeria, etc.

Since 1972, the National Front has known four phases:

- 1972–87: the National Front appears as an anti-communist group that is against migration and abortion. Under the leadership of Jean-Marie Le Pen, it tries to get rid of its more radical militants. In 1984, it wins 10 deputies in the European elections and makes an alliance with the right wing in Dreux for a municipal election, getting one post on the municipal team. It introduces to public opinion two themes that will become more and more central on the official political scene: migration and insecurity.

- 1988–97: the National Front tries to enlarge its electoral basis and wins 1,350 municipal councillors.

- 1998–2011: the party splits between those who wanted to make an alliance with the right (led by Bruno Mégret) and those who want to explode the right (led by Jean-Marie Le Pen). The National Front loses 40 percent of its members, 500 municipal councillors out of 1,250, 3 meps out of 12, etc. Despite that, Jean-Marie Le Pen succeeds in eliminating the Socialist Party candidate in the first round and reaching the second round of the presidential elections in 2002. Marine Le Pen joins the party in 1997 and becomes a star in the media between the first and second round of the presidential elections in 2002.

- 2011–17: After the Tours Congress in 2011, Marine Le Pen becomes the president of the party and, with the help of the media,[2] succeeds in convincing more and more electors that the National Front has changed. She marginalizes her father and most of his old followers, and accentuates a “social” turn that her father had already started. She mobilizes the party around a protectionist and sovereigntist policy, critiques the European Union and the Schengen agreements; she is hostile to the freedom of circulation, denounces an American-led globalization, etc. She also tries to get rid of the anti-Semitic reputation of her party by proclaiming that the National Front is “for the future, the best shield to protect them,” even if her critique of “nomad” and “stateless” finance, her denunciation of famous Jewish intellectuals, are always borderline…

So, after this brief historical introduction, I would like to deal with the theme of my speech today: how does the National Front control its municipal territories?

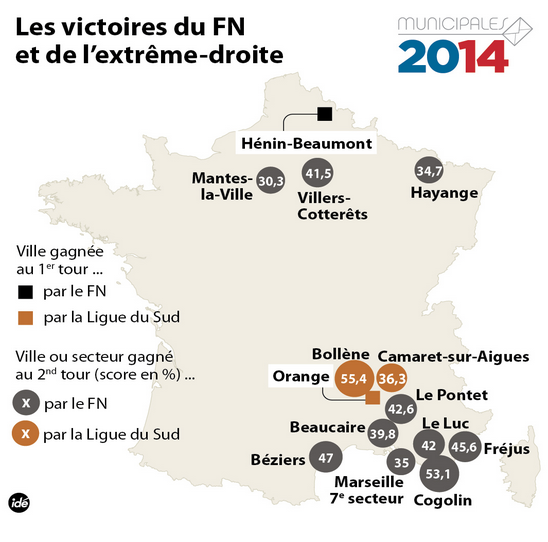

Today, in 2017, the National Front manages 11 towns or districts ranging from 10,000 to 150,000 inhabitants each—one near Paris, two in northeastern France and eight in southern France.[3]

To illustrate the National Front methods, and explain how it controls a specific territory, I will mainly draw upon the examples put together by a network of “anti-fascist trade-unionists” (visa[4]) covering all France and a book written by a Green municipal councillor in Hénin-Beaumont.[5] This town is a model hailed by Marine Le Pen and which any local section of the National Front is encouraged to follow, if it wants to conquer local power.

I prefer to use the expression “national-populist” to characterize the National Front and not the term “fascist,” but I will not deal today with this problem.[6] It seems to me more important to clearly understand how the National Front operates in the bourgeois-democratic system that has enabled this party to thrive without any legal repression. If one thinks of the National Front only as a violent group using thugs, clubs, razors, daggers, and guns, one will have a hard time understanding how this party won 11 municipal elections in France and 24 seats in the European Parliament in 2014, and 8 seats in the French Parliament in 2017. It will be difficult to understand how it grew from 2 million votes in the European elections of 1984 to 6.8 million votes in the regional elections of 2015 and 10.6 million votes in the last presidential election in May 2017, even if these numbers drastically declined during the Parliamentary elections in June 2017: 2.9 million votes at the first round and 1.6 million votes at the second round.[7] Its evolution has been rather chaotic, with many ups and downs but has known an uncontested growth.

Today I will try to analyze how the National Front mayors and their municipal teams maintain and enlarge their power, once they are elected. One can identify ten main tools used by the National Front to control the territory of a municipality and its inhabitants, even if there are obviously nuances and differences according to each mayor’s personality and to each specific local socio-political situation. So obviously my description may appear oversimplified, as it tends to put together all the negative aspects of the National Front policy into one coherent model, despite the multiple contradictions and incoherencies which characterize this party.

1. First, the National Front tries to silence municipal staff members who sympathized with the left if the town had been administered by the Socialist or the Communist Party. In case the right ran the town, the task is much easier as it shares many ideas with the National Front.[8] If, before 2014, Hayange, Hénin-Beaumont, Villers-Cotterêts, Le Luc, and the 7th sector of Marseilles were managed by the left, Le Pontet, Beaucaire, Béziers, and Fréjus were administered by the right. As for Orange, Bollène, and Camaret-sur-Aigues, ran by the Ligue du Sud since 2014, a group which is almost a clone of the National Front, they were in the hands of the far-right (Orange since 1995) and of the left (Bollène, Camaret-sur-Aigues).

To fulfill its aim, the National Front mobilizes the traditional techniques used by managers and bosses in any company or administration. It targets the executives who are left-minded and tries to push them to quit their jobs on their own will; to create divisions among the municipal employees, the National Front’s militants spread all sorts of rumours (including about their love affairs); the mayor obliges the left municipal employees and executives to change their office, floor or building; the National Front puts its political opponents in isolated offices to demoralize them; it gives them tasks which are absurd or impossible to perform and then sanctions them for not having done them properly; it asks its most obedient employees to spy and report all the actions and discussions which involve left-wing municipal employees, etc.

If the unions organizing municipal workers have a militant attitude, the fn targets the most active members, by increasing the amount of defamation and even by threatening the trade unionists as well as all municipal employees with disciplinary procedures, such as in Hayange. The municipal staff is supposed to express itself “with restraint, outside their work, in their private life, on the Internet and in its e-mails.” This apparently restrictive policy does not prevent the mayor of Hayange from asking its employees to distribute leaflets attacking the local cgt union.

In its municipalities, the National Front recycles candidates who failed to be elected in other constituencies and hires a number of neo-fascist activists. The National Front also uses the services provided by communication and security companies, mutual insurance companies, consulting agencies founded by members of the far-right (gud, fane, œuvre française, etc.).

2. The National Front intensively uses the media in a very aggressive way:

- the local municipal magazine, both to promote the “good deeds” of the municipal team and to attack and slander the left municipal or regional councillors, or left-wing regional mps. As expected, in these municipal publications, the opposition has a very limited space to express its views;

- the regional bourgeois dailies, if they agree to propagate the main ideas of the National Front and publish, without any critical comments, its press releases. When the local media (La Voix du Nord in the north or Var Matin in the south, for example) dare to criticize the party or just try to practice some form of “objective” journalism, the National Front systematically asks for a “right to reply”; its militants even demonstrate in front of the local newspaper’s headquarters to protest against its political line.

- The social media, Facebook,[9] Twitter, and all sorts of official and unofficial[10] websites and blogs. The National Front has become very efficient on this ground and enjoys many far-right allies (agitators like the fascist Alain Soral but also “independent” websites like FdeSouche, Le Salon Beige, Novopress, etc.) who do its job and multiply the effect of its propaganda, videos, racist “jokes,” etc.

3. The National Front spies on the local population. The Internet and social networks are useful not only to propagate the ideas of the National Front, to slander and viciously attack its opponents (calling them “alcoholics, bums, scumbags, hysterics, donkeys” etc.), but also to watch what their inhabitants think, especially municipal employees but also all the local personalities including priests, rabbis, imams,[11] and ministers. The information collected on the social media is used to organize a systematic harassment by e-mails, sms, and messages on Facebook to pressure the National Front’s opponents or critics. Anonymous phone calls, death threats and calls to rape left-wing militants are also quite frequent in the National Front municipalities.

4. The National Front does not limit itself to intimidating its political opponents. It also tries to exert pressures on two groups of local protagonists: the shop owners and the non-political associations.

For example, the municipality boycotts any restaurant or pub owner who welcomes a left-wing or anti-racist social event. This boycott can lead to a hostile campaign in the municipal newspaper and on the social networks, blogs, and websites controlled by the National Front or its allies, but also to multiple anonymous calls, refusals to deliver certain legal authorizations, etc.

Apart from political events hosted by restaurants or pubs, all shop owners are pressured to accept, inside their commercial premises, municipal posters that convey political messages, and to explicitly support the municipality in their own advertisements, letterhead paper, etc.

As regards the associations that organize guitar classes, promote sports[12] and leisure activities, the pressures are even more efficient and direct as those associations depend on municipal funds or municipal premises that can be very easily diminished or suppressed.

Although it has tried to build a pseudo-“feminist” image, the National Front is opposed to associations like the “Planning familial” (Family Planning), which helps women and informs them about contraception, sexuality and abortion. In Le Luc, for example, the “Planning Familial” has been obliged to cease its activities because it was not financially supported by the municipality.

5. The National Front uses the bourgeois-democratic structures to destabilize left-wing municipal councillors. When there is a meeting of the municipal council:

- the National Front mayor and municipal councillors interrupt the left-wing councillors all the time;

- in Hénin-Beaumont, the members of the opposition are obliged to sit with their backs to the public, while the National Front municipal team is facing the audience;

- in Hénin-Beaumont, Hayange and Fréjus, many local National Front militants come inside the meeting room, talk loudly, or even bring food and drinks, and make noise when left municipal councillors are presenting a motion, or express their disagreements with the mayor’s policy, etc.

Faced with these vicious methods, what do the reformist left militants do?

- They often accept being treated with these anti-democratic methods because they don’t want to be considered as “trouble makers.” They don’t shout, they stay calm while being interrupted, insulted and booed in the municipal council meetings.

- They accept participation in ceremonies to commemorate the French Resistance, or against anti-Semitism, and they are unable to create their own events on the same themes. They even protest when they are not invited, which is rather strange for parties who insist on labeling the National Front as “fascist”!

- They accept being mistreated at public events organized by the mayor because they don’t want to appear as violent “leftists.” And because they share the fiction according to which the State and its municipal instrument are neutral and should serve all citizens.

- They even organize the May 1 celebration with the National Front mayor and the trade union leaders, and whine when the mayor denies them the right to use the municipal equipment!

- They protest against the “rudeness” and “authoritarianism” of the National Front mayors and their collaborators, as if it was a proof of their supposed “fascism,” forgetting that more polite and more “participatory” methods may be as efficient to impose reactionary and anti–working class ideas and measures.

- They only carry out legal actions: petitions, informative meetings, articles in the press and social networks, legal complaints, and trials.

6. Defending French popular culture, national patrimony and identity, the National Front wages violent campaigns against “sick minded, degenerated, paedophile, pornographic, elitist” artists, i.e., modern painters, musicians, sculptors, dancers, etc. And the party even requests them, as in Villers-Cotterêts, “to respect the principle of political neutrality in the framework of their artistic performance.” In Fréjus, artists and artisans have been expelled from the premises rented to them by the previous municipality for a cheap price. In Marseilles, the National Front votes against any cultural project presented by the other parties.

The National Front campaigns range from petitions and demonstrations to repainting in blue a sculpture which did not correspond to their taste, like in Hayange; or banning a film poster about a lesbian love story, like in Camaret-sur-Aigues. The cultural views of the young National Front mayors are incoherent as some of them love rap, heavy metal, and techno music, and don’t hide their musical tastes when they go to dancing clubs or musical events. But this cultural duplicity does not matter for them. Beyond their personal tastes, they find it more important to target the frustrations of their most traditional voters; to denounce, as in Cogolin, “oriental dance” classes in order to send a message to xenophobic or racist voters. Therefore they try to restore all sorts of ancient Roman, Provençal and medieval festivals, as long as they contribute to the revival of local cultural traditions[13] and give them a super “Gallic” political image.

But at the same time, on the National Front website, the party promotes the figure of Jean Vilar, a famous theater director and Communist Party fellow traveller, as a model of resistance against anti-French cultural globalization!

7. The National Front mayors wage war against the poorest inhabitants—the precarious workers, the single parents or couples who are unemployed and who ask for reduced prices for school meals or free meals so that their children can eat at the canteen. In Le Pontet and Beaucaire, this is an indirect way of applying a racist and discriminatory policy against “foreign” Franco-African or Franco-North African families who often belong to the poorest social layers. In Beaucaire, the mayor went as far as threatening to sue the parents who did not pay the canteen on time and denouncing them to the caf[14] and to the child protection services.

Anxious to save money at the expense of the working population, the National Front mayors try to make their constituents pay for services which were previously free: school buses, extracurricular artistic activities, supervised study sessions at the end of the day, etc. They reduce the subventions to social centers (which organize many activities for young people in lower-income neighbourhoods); to social action centers (which provide financial help outside the rsa[15]); and to leisure centers that organize children’s activities during school holidays.

They stop providing premises or giving subsidies to the cgt trade union, the fcpe (parents’ association) and to groups which have social activities such as the Secours Populaire; and they refuse to vote credits to rehabilitate social housing.

Obviously, all these measures may also have negative effects on poor Franco-French families. So the National Front mayors make a lot of publicity about their support to the “Restos du cœur[16] like in Hénin-Beaumont, and, from time to time, try to help Franco-French families who are in material distress.

8. The National Front tries to pit one part of the population (the foreigners, the French people of foreign origin, the “Muslims,” the “dishonest parents,” etc.) against another (the Franco-French, the people of “Judaeo-Christian” culture, the Catholics, the Christians, the “honest parents,” etc.), without always using an openly offensive language, in order to avoid being sued for stimulating racist or religious hatred. They refuse to welcome refugees in their cities with alarmist posters (in Béziers). National Front mayors and municipal councillors use many euphemisms and paraphrases (like, for example, “we have to help ourselves before the others”; “some people who arrived on our territory are more equal than others”) to develop their implicitly racist and xenophobic ideas.

They do not hesitate to attack the living conditions of children by increasing the price of the school canteens (in Beaucaire, Le Pontet, Villers-Cotterêts); by suppressing subsidies for school tutoring and by complaining about being legally obliged to finance French courses for “allophone” pupils (in Beaucaire).

They try to divide the population along religious and nationality lines: in Fréjus, they claim that a new mosque should not be built next to a “Christian” cemetery (which was, in fact, a municipal, non-religious, cemetery). They forbid Christmas shows for parents who do not have a French identity card in Marseilles. In Villers-Cotterêts and Béziers, they struggle to set Christmas nativity scenes in town halls, even if the state administration and judges prevent them from doing so.

The Roma are the social group that suffers most from racial prejudice in France. Their annual pilgrimage to the Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer (in the south of France), which has taken place without any problem for years and which mobilizes tens of thousands of people coming from all over Europe, is regularly targeted by the mayor of Cogolin, who invites its constituents to denounce any criminal act committed by the “travellers,” while the mayor of Hénin-Beaumont, in the North of France, takes measures against the beggars.

9. The National Front uses its municipal bases to propagate and trivialize the main theses of the far right:

- It refuses any “repentance”; in other words, it refuses to expose the crimes committed by French colonialism (particularly in Algeria, which is always a sensitive issue, and which leads the National Front mayors to rehabilitate the oas, a far-right terrorist organization opposed to the independence of Algeria) and the consequences of slavery, notably in the French West Indies.

- In Mantes-la-Ville, it defends xenophobic and racist ideas: for example, it denounces “racial intermingling,” considered as a form of “eugenism which dilutes identities”[17]; in Marseilles, it forbids municipal employees to speak any language other than French with customers and among themselves; in Béziers, it supports the pseudo-theory of the “Great Replacement”[18] close to the Eurabia myth.

- It equates Nazism and communism (i.e., Stalinism) which helps to “excuse” the holocaust deniers, the nostalgics of Marshal Petain, and so on. But, more important, the National Front compares these forms of totalitarianism to the European Union and contemporary institutions (imf, World Bank).

- Instead of minimizing or excusing fascism or Nazism by the necessity of fighting a non-existent “communist” danger, the National Front militants present themselves today as the real heirs of the Resistance against the “collaborationists,” i.e., the left and right mainstream parties which support globalization, migrations, Islam, the disappearance of national identities and multiculturalism. Therefore, today, it’s the far right that accuses the left and far left of being Nazis or fascists!

- When the National Front denounces migrants, it tries to use less racist terms than before (even if this is probably very painful for its militants). For example, promoting a form of “ethno-socialism”[19] or of “welfare chauvinism,” it strongly criticizes the bosses who use migrants as a way of keeping the wages of the Franco-French workers at a low level. Marine Le Pen defends” a “patriotic protectionism” or a “social patriotism.” Therefore, she presents[20] the migrants as the first victims of the globalization and the Muslim migrants as anti-Republican (obviously also as potential terrorists).

- Islam is presented as a religion which is more dangerous and harmful than the other religions and incompatible with democracy, since now a good part of the French (but also European) far right pretends to defend the values of the Enlightenment, the republican system, direct democracy and the “Judeo-Christian” European civilization against what they call “Islamo-fascism.”[21]

- As stated by Michel Eltchaninoff,[22] the National Front has a very peculiar conception of secularism (laïcité in French): “The Lepenist view of secularism…considers that, given their historical roots, some religions have more rights than others. Secularism must protect the Christian religion, which belongs to the French identity, against a newly established religion…. [Marine Le Pen considers secularism as] an instrument of Christian France to defend itself from a religious invasion.”

- The National Front propagates conspiratorial views about national and international affairs,[23] so we should not be surprised that its electors are the most attracted to conspiracy theories.

- It defends a “patriotic” vision of ecology and animals’ rights.

- It fights against “materialism” and “consumerism.”

If the National Front cannot implement its xenophobic, racist and socially reactionary ideas with local concrete measures, it does not matter. Its aim is to accustom French citizens to hear this discourse; it wants to make the most of the scandals created by its so-called “verbal blunders” to spread the ideas of the National Front. In short, the party uses the old method of “provocations” and “sound bites” invented by Jean-Marie Le Pen, but this time delocalized and multiplied in all the territories where the fn manages a municipality. And we should remember that this party benefits not only from its dozen municipalities but also from more than 1,500 municipal, regional and departmental councillors, which cover a much larger territory than the approximately 410,000 inhabitants directly concerned by its municipal decisions and propaganda.

10. A last tool is used by the National Front: the municipal police supported by cctv cameras and local informers.

In France, the state police (143,000 agents) have the right to bear weapons and it’s also the case for 40 percent of the municipal police forces (that is: 8,000 among 21,200 agents). Everywhere it has gained local power, the National Front creates a municipal police (or enlarges its existing staff). This municipal police is sometimes sent to prevent left militants from distributing leaflets in public spaces, as in Fréjus and Hénin-Beaumont; or to prevent its opponents from speaking during a municipal council meeting, as in Cogolin[24] and Hayange (the mayor frequently provokes its opponents and, if they answer back aggressively, they are expelled from the meeting room).

The National Front mayors control their territories with surveillance cameras and incite their constituents to expose municipal employees (like those citizens of Béziers who reported the municipal street sweepers who supposedly “did not work.”.while they were on break) and to become official “district correspondents,” i.e., police informers. The mayor of Béziers went as far as calling for the creation of a militia (the “Garde biterroise”), which was supposed to regroup former police officers, gendarmes, soldiers and retired firefighters. Thankfully, this initiative was outlawed by the courts.

After such a negative catalogue of reactionary measures, maybe I should try to list a few things which the local population may consider as positive: the National Front mayors try to answer all letters, as quickly as possible; they repaint the town centers and repair the holes in the streets; they try to organise as many parties, events and celebrations as possible to revive local life in towns which suffer from a high level of unemployment; and, as they cut many social expenses (but never in their own wages!), they try not to increase the local taxes.

***

Faced with such a determined and sneaky politics, one can’t trust the reformist left because its municipal councillors (not to mention its mps and senators) will never endanger their official positions and the future opportunities they covet.

So what should we do? Old recipes won’t work, as shown by the various strategies put forward by the left and the far left during last the 40 years in France. Almost every tactic has been tried and has failed: the street confrontation of the (Trotskyist) Communist League and of the Maoists against the neofascist Ordre Nouveau in the 1970s; the passivity and abstention of the Trotskyist Lutte Ouvrière, which was supposed to build a workers party and deal later with the National Front danger; the moral denunciations of the Socialist Party and the campaigns of the “SOS Racisme” association with its famous slogan: “Touche pas à mon pote” («Don’t touch my pal»); the call to vote for Chirac and more recently for Macron. None of these tactics has prevented the National Front from becoming stronger and getting more and more votes.

I can only repeat the very general conclusion of my article written in 2014:

“We have to come back to basic old revolutionary ideas:

- elections should NOT be our main field of activity, contrary to the tradition of the French far left during the last 40 years;

- we should always put forward internationalist or, better, a-nationalist principles and slogans instead of courting nationalist prejudices as the far left often does on national or international matters;[25]

- we should wage an ideological fight against the far right and the New Right, but also against all those who, in the left or the working-class movement, propagate their ideas, consciously or not.”

The left and far left are not ready to confront racist and nationalist prejudices which contribute to the National Front’s growing influence. They know how to make moralizing “anti-fascist” speeches, but they never seriously fight for concrete measures such as:

- the right to vote for all foreigners,

- the right for foreigners to be hired in all public services,

- equal rights for all social benefits (housing, health, education, etc.),

- welcoming all refugees, etc.

These basic demands have never been central or even important in any electoral campaign of the left and far left during the last 40 years. Outside of this political framework, I don’t see any possible progress in the struggle of the far left against the National Front.

Any illusion that voting for left-wing candidates will stop “fascism” is nonsense (opposed to all the lessons of history) and a criminal illusion.

The Socialist Party, the Communist Party, the Green Party, etc., would not do anything against the National Front if they were in power, locally or nationally. And we have been able to verify this in France during the 17 years the left was in power: 1981–86, 1997–2002, 2012–17. They will calmly discuss with the National Front as they have done while this party has gained many municipal and regional councillors, and a few mayors and mps. They will complain that the National Front does not respect democracy, but they will not confront it seriously by force or even using the law.

Map published by “20 minutes.”

Deindustrialization and workers’ votes

If we want to properly fight the National Front and national-populist parties in Europe, in general, there are at least two elements that we should consider:

A. In a situation where deindustrialization has fragmented workers and erased the traditional image of the local boss as a visible enemy, the national-populist parties have focused their energies on a new national enemy with two heads: the migrants (or “foreigners”[26]) and the European Union. And they have been quite successful in giving flesh and blood to this enemy and erasing the capitalist enemy from the minds of part of the working-class voters, especially those who already voted for the right and had reactionary ideas.

Deindustrialization[27] has led to the disappearance of a visible and close enemy: for example, in the case of northeastern France, the owners of the mines, big steel industries, textile industry, etc. The National Front has replaced the old social enemy (the boss) by a national enemy, a hydra with two heads: the migrants (and the “foreigners”) and the eu (and its so-called “Euro-crats”[28]).

The stable working class world of those who were employed in the same company for years, sometimes generation after generation, or even for a lifetime: this world has disappeared. It has been replaced by permanently moving social relationships:

- the name and the nationality of the boss (or of the multinational group) which owns the company, changes all the time;

- the workers change jobs regularly because their former qualifications are no longer useful on the labor market;

- they work more and more for temporary employment agencies, are often obliged to become self-employed, and depend on companies whose size is much smaller, thanks to outsourcing.

The fact that the size of most production units is smaller and that more and more blue-collar workers work in the service sector but are isolated from others means that they identify less and less with the working class and that the theme of national identity is more attractive to them. “Today, more than two out of five workers work in the tertiary sector, as drivers, stock-keepers or warehousemen, or in fast-growing commercial services (temporary work, cleaning), in situations of isolation and precariousness…. A low-skilled proletariat is developing in the service industry where the frontier between the blue-collar worker and the white-collar worker becomes blurred.”[29]

As noted by Olivier Schwartz,[30] the Franco-French workers who have a more or less stable status in the private and public sector tend to see themselves trapped between, on one side, the “top” (the rich and the powerful, those who are at the head of the state, the corrupt or incompetent politicians) and, on the other side, the “bottom” (the migrants “who don’t want to be integrated,” those who only “live on benefits and don’t bother to look for a job,” the delinquent youth). As they think they are the victims of the richest as well as the poorest individuals, such a twisted form of class consciousness helps the National Front to propagate its reactionary vision among the popular classes.

According to Valérie Igounet and Stephane Wahnich,[31] the main reason why workers vote for the National Front is not because they are unemployed (the map of unemployment does not correspond to the map of the electoral successes of the National Front); it’s no longer a vote to protest against the left as it was in the 1980s, but a vote of fear: the fear of losing the “advantages” of the welfare state, of becoming unemployed, of living in a much less protected society, with much more daily violence, the fear of coexisting tomorrow with Muslim migrants and violent youth with a foreign background.[32] According to the two historians, it’s a militant and therefore persistent vote which corresponds to the desire to “find a job in the region where they grew up, the possibility of getting the job they have been dreaming about,” all that thanks to a public policy which will enable “an equilibrium between the respect of nature and re-industrialization” and the creation of “small industries which will cause only a reduced pollution” (Marine Le Pen dixit). This dream has been selling well to part of the right-wing workers who have been more and more attracted to the National Front.

If we take the example of the economy of the Nord-Pas-de-Calais region,[33] today it is mainly organized around services and distribution companies which import goods produced in other countries, no longer in France.

In such a situation characterized by intense changes and the related disorientation, the National Front offers a cheap and illusory solution to its voters, which acts as a band-aid on a serious injury, but which is happily accepted by a growing part of right-wing workers. The National Front proposes to revive all local traditions, be they local food specialties, Catholic events or Provençal folk dances. In these small towns (remember the National Front until now has won power mostly in small towns) the party offers to pauperized Franco-French workers some distractions, a nationalist substitute and a temporary answer to their social frustrations.

These social frustrations are growing because, on the labor market, the competition is growing between the workers and the unemployed, between Franco-French and foreigners or French people with a foreign background, etc. This competition exists also in the school system: Franco-French working-class parents want their children to succeed and fear that “foreign” pupils may impede their sons and daughters to study properly. This leads to conflicts inside the school but also inside the working class districts between the youth of different national origins. These conflicts nurture the propaganda of the National Front and enable this party to deepen, in some workers’ minds, an ethno-racial cleavage which will have long-term consequences.[34]

As the power of a mayor is limited in France, especially if he (or she) rules a little town, the National Front can play two cards at the same time: on one side, it treats and solves a limited number of difficult personal situations, and on the other side, it leaves most social problems unsolved, while explaining to its electors that the municipality has limited means. Therefore it tries to persuade its electors to also vote in parliamentary and presidential elections, so when the National Front will have full power, it will be able to solve all problems thanks to seven simple recipes—it will:

- miraculously give jobs only to the French nationals;

- expel all the foreigners who are unemployed for a long time or have been condemned to prison sentences;

- revoke the French nationality of all the foreigners who have been recently naturalized and of all those who have committed crimes;

- close the French frontiers to stop “those barbarian hordes who pollute our cities”;

- set up a stronger state with tougher cops and a stricter justice, which will solve all the daily difficulties in the working class districts and eliminate the dictatorship of the communities (“communautarisme” in French) and the “tribalization” of French society; this strong state will also control the press, forbid “illegitimate demonstrations” and favor “free” (?!) trade unions;

- organize a referendum about the reintroduction of the death penalty,

- and re-establish the Franc.

B. The relationship between the workers and politics on the electoral level has been radically modified. This phenomenon contributes to the growth of national-populism, a political current that actively uses all traditional and new media as well as polls to influence public opinion.

Before the multiplication of television networks in the 1980s, followed by the appearance of the World Wide Web and its massive expansion after the middle of the 1990s, and the appearance of the social networks (Facebook was created in 2004), the votes of the workers were influenced by four main elements:

- the dense presence of local militants in the trade unions, the tenants associations, the sports associations and all sorts of cultural municipal structures,

- the militant press (daily, weekly, monthly), sold in the streets, on the markets and at the doors of the council flats,

- the mass meetings of the left,

- and the interventions of reformist leaders on radio and television which were explicitly directed at the working class.

Today, the importance of these four main factors has declined, or even disappeared, and new relationships appeared between workers, political ideas and the act of voting:

- workers read the left press less and less and, anyway, the number of left publications and their distribution have been drastically reduced;

- the number and activism of left militants has seriously declined;

- workers have more and more access to all sorts of confusionist, conspiratorial, far-right websites, videos, Facebook and Twitter messages, etc., which are supposed to provide alternative information but, in fact, propagate stupid rumours, anti-Semitic ideas, conspiracy theories and fake anti-capitalism. This pseudo–anti capitalism is based on the denunciation of some corrupt politicians or extremely rich individuals, on a vague critique of a mysterious “oligarchy,” “caste” or “globalized hyper-class,” “elite (s)” and excludes any clear vision of capitalist relations of power and exploitation.

The French Socialist Party centers all its propaganda and recruiting efforts on the cultural middle classes and does not care anymore about the working class, even in words. The Communist Party has lost its industrial base in key industries, its propaganda is softer and softer, and also directed towards the salaried petty bourgeoisie.

This context (mass influence of the television networks; political “culture” based on lousy videos, clips and short messages on Twitter and Facebook; decisive role of political polls; Socialist and Communist parties’ lack of interest in the working class) has helped to build new political figures: Berlusconi, Le Pen, Trump, Beppe Grillo, Pablo Iglesias, Mélenchon, Fortuyn, Blocher, Wilders, etc. It has introduced new elements to influence working-class voters.

A more or less subtle use of the official and alternative media (a manipulation which is even easier if you own them) helps to influence the voters outside the party (or the movement) that one is trying to build. But this use of all official and unofficial media also helps to influence and even change the balance of forces inside the national-populist parties.

For example, Marine Le Pen used the media to defeat, inside her organization, both the old traditional national-Catholic tendency, and those with a nostalgia for fascism, Nazism or the French colonial empire. So these tactics enabled Marine Le Pen to make public opinion believe that her party had totally changed under her leadership.

As regards the National Front electors, in the long term, only 3 percent of the voters remain truthful to this national-populist party, and at every election 50 percent of the voters are new electors. This huge electoral turnover shows the volatility of the National Front electorate (which could be reassuring) but also the lack of political consciousness of the voters (which is much more preoccupying).

How do the far left and anarchist movements react to these evolutions?

- The far left does not understand how the media (the main television channels, the Web as well as the social networks) have been replacing the traditional political organizations of the working class. As noted by Remy Lefebvre, the media have become “the intermediaries between the public opinion” (including the working-class public opinion) “and the ruling class.” In such a situation the media “devaluate the role of militant and party spaces as places where one can construct political alternatives.”

- The far left does not know how to use the social media and especially video techniques, in a creative and funny way. (For example, the presidential candidate for the New Anti-capitalist Party, Philippe Poutou, an automobile worker, appeared in a very silly video produced by his comrades, during the last electoral campaign.)

- The far left has not succeeded in building a significant presence on social networks and it is not rooted in working-class districts.

- The far left still views the activities of elected representatives inside the bourgeois state as the leaders of the early twentieth-century workers’ movement, who wanted to use the municipalities and the national parliaments as a tribune to “educate the masses.” It has not understood the changes that have taken place inside the bourgeois democratic institutions and just struggles to revive a decomposing corpse.

- Confined to the universities and the salaried petty bourgeoisie, the far left and anarchist movements have adopted one form or another of identity politics that leads them to adopt confused and indeed reactionary theories. Therefore, it’s not difficult to understand why they are unable (and would be unable even if they wanted) to get serious roots inside the working class.

Who are the members of the Central Committee?

Although the Executive Bureau (six members) and the Political Bureau (42) have the real power in the National Front, and although the Central Committee does not meet often, it’s nevertheless interesting to analyse who its members are, as they are directly elected by those who have paid their membership fees. Among its 100 elected members and 15 co-opted members:

- Thirteen have never worked and only occupied representative functions in the National Front apparatus and/or in the bourgeois state. Most of them are less than forty years old and have profited from the recent growth of the National Front to get an easy job as a party full-timer or an elected official. Those who have work experience are generally over forty and have been obliged to earn their living without counting on political remunerations and advantages.

- Twenty-three are mps and senators (four have been elected to the French Parliament, 17 to the European Parliament and two are senators);

- Sixty-eight are locally elected officials (and 36 of them had two or three elected jobs at the same time, at least until the elections of June 2017).

In terms of university degrees, at least twenty members have continued their studies after high school either in an engineering school, on in a university (law, political science and economics, disciplines which traditionally help for political careers).

Thus, one can better understand why the anti-“elites” rhetoric can seduce men and women who have an academic level much lower than that of the leaders of the institutional right or left.

About the social composition of the Central Committee, it includes:

Nineteen National Front full-timers (this is an approximate number as the official biographies of National Front members are often quite opaque),

- 17 executives of the private and public sector,

- 14 small company managers and entrepreneurs,

- 10 members of the repressive apparatus (police and military forces[35]),

- 9 lawyers,

- 6 primary and secondary school teachers,

- 5 engineers,

- 5 university teachers,

- 5 sales representatives, real estate agents and commercial agents,

- 4 shop or restaurant owners,

- 2 nurses,

- 2 doctors (1 general practitioner-geriatrician, 1 surgeon),

- 1 employee,

- 1 artist,

- 1 farmer, and

- 1 artisan

So, these statistics show us that, for the moment,

- The leaders of the National Front do not belong to the working class[36] or even to the “popular classes,” if by “popular” we mean those who hold a subordinate position in the division of labor.

- It includes a significant proportion (41 out of 115) of executives, company managers and bosses, cadres of the military forces who are direct agents of capitalist exploitation and domination.

- It welcomes an important proportion of the “intellectual middle classes” (20 lawyers, doctors, teachers and university graduates) who are massively present in the leadership of all bourgeois parties.

- It welcomes a significant proportion of people (13) who have no work experience and always relied on the National Front to pay their bills.

- The leadership basically relies on two legs: its full-timers (19) and its 68 locally elected militants (37 municipal councillors, 53 regional councillors, including 21 who are also municipal councillors, 4 departmental councilors and 9 mayors) and 23 mps and senators who often have also local responsibilities (12).

Until 2017, the National Front has chosen the best electoral districts for its favorite militants and thus given a lot of power in leadership organs to those who were able to win elections on several levels at the same time: municipal, regional, national and European.

Let’s now study more in detail what these elected posts are and what material advantages they provide for their beneficiaries.

A municipal councillor of a town regrouping less than 100,000 inhabitants (which is the case of most National Front municipal councillors) does not earn any wage, so he (or she) can’t count on this “job” to earn a living. This explains probably why so many National Front municipal councillors are also regional councillors. If they want to live from politics (“at the expense of the tax payers,” as the National Front usually says when it criticizes other politicians), they need to get elected at the regional level, if they live in small towns with less than 100,000 inhabitants: for a regional councillor, the wage varies between 1,520 euros and 2,661 euros according to the size of the region, so it’s a decent wage, especially if combined with other material advantages or free-lance activities or party financial help.

The National Front has 358 regional councillors… more than the Socialist Party (355)!

One thousand five-hundred eighteen National Front municipal councillors were elected in 2014. Today, in 2017, one third of them have disappeared: some moved to another town, a majority were disappointed by the National Front and decided to abandon their “job,” and some thought it was more convenient to present themselves as “independent” for their local political ambitions.

An mp earns 5,148 euros per month but can spend 4,490 additional euros per month for the expenses linked to his job, and 7,400 euros per month for his staff. The National Front had only two mps until June 2017 and has now eight mps. A senator earns 5,405 euros per month plus 4,700 euros per month for expenses linked to his job, and he receives 5,500 euros per month for his staff. The National Front has only two senators.

The wage of the eleven National Front mayors depends on the size of the town they are managing:

- Between 3,500 and 9,999 inhabitants = 2,090 euros (1 mayor)

- Between 10,000 and 19,999 inhabitants = 2,470 euros (6 mayors)

- Between 20,000 and 49,999 inhabitants = 3,421 euros (1

mayor) - Between 50,000 and 99,999 inhabitants = 4,181 euros (2 mayors)

- More than 100,000 inhabitants = 5,512 euros (1 mayor)

A European deputy (the National Front has 24 European deputies) earns 6,200 euros per month and receives 4,300 euros per month for the expenses linked to his job, plus 4,243 euros for his travel expenses.

What about the age of the leaders, and which generation has most power inside the National Front leadership?

If we study the age of the 100 members of the Central Committee and the eleven militants co-opted in 2014 (even if some have quit the leadership or have been expelled since):

Generally among those who have started being active after 1988, one can observe a quick ascension as full-timers (9 full-timers out of the 19 who are members of the Central Committee are between 24 and 34 years old), mayors (all of them, except one, are between 30 and 45 today), mps (4) or senators (2).

Most CC members have joined the National Front after 1987. Only 13 out of 115 joined before 1987, and, among these 13, only 3 participated to the foundation in 1972.

If we look at their age, now in 2017 we find

- between 20 and 30: 10

- between 30 and 40: 17

- between 40 and 50: 29

- between 50 and 60: 14

- between 60 and 70: 28

- between 70 and 80: 8

- over 80: 1

So the majority of the leaders (56 out of 115) have not known the Indochina and Algeria wars, the 1960s and 1970s, and the difficult times of the National Front before the European elections of 1984.

Most National Front leaders and cadres have joined the National Front after 1988, a turning point in the electoral history of the party, after which its influence at the ballot box and in French political life has steadily grown, to the point of determining the positions and vocabulary of the French left and right. A good proportion of the party cadres did not have any other political experience before joining the National Front. And some of the youngest joined the National Front when they were 13, 15 or 16 years old. They think that their party will enjoy a very bright future and that they will benefit from it. This can only push them to blindly stick to the party line (i.e., the one determined by its leader), to never criticize[37] the leadership, and to defend its most reactionary ideas.

Men who have no work experience (at least from the information available on the Net and on the National Front websites) are either full-timers or elected officials. (This means obviously I don’t consider full-time elected jobs as “work” but as a parasitic activity…) Women who have no work experience are most of the time women who dedicated their lives to raising their numerous children (and they are proud of it, as can be seen on some of their videos) and depend on their husband’s wage. This classic division of labor between men and women illustrates how the “feminist” image of the National Front is a lie, even if Agnès Marion, member of the Central Committee, can declare:

It is necessary to revalorize the image of the women who decide to raise their children by slowing their careers. A woman who makes this choice is not a “quiche” [i.e., stupid] and her choice must be recognized. Mothers have a sense of reality, practical intelligence, they are not disconnected from everyday life. Without my experience as a mother of a large family, I would not be able to manage my husband’s business with the same rigor and dynamism.[38]

The women of the National Front (at least those whose husband belongs to this party) religiously apply the party line[39]: most of them have between 2 and 6 children, which is probably linked to their Catholic family traditions in most cases.

- [1]My articles about the National Front are included, with other texts, in the book What’s New in France for the Left. They are also available on mondialisme.org and npnf.eu websites: “Behind the rise of the National Front” (2014); “The National Front and its influence among French workers” (2015), which is divided into 3 parts: “The National Front and French working class,” “Some clichés and preconceived ideas about the National Front,” and “French antifascism in France.”↩

- [2]Between 1983 and 1997 Jean-Marie Le Pen appeared 75 times per year on tv. But his daughter appeared 842 times per year between 2011 and 2013, while the Socialist Party’s General Secretary only appeared 200 times!↩

- [3]The name and population of these towns are respectively Le Luc, 9,500; Villers-Cotterêts, 10,090; Cogolin, 12,517; Beaucaire, 15,505; Hayange, 15,757; Le Pontet, 17,476; Mantes-la-Ville, 19,858; Hénin-Beaumont, 26,278; Fréjus, 52,953; Béziers, 75,701; and one district of Marseilles, the 7th sector, 150,971. To these cities one can add three other small towns managed by the Ligue du Sud (Southern League), a group very close to the National Front: Camaret-sur-Aigues, 4,500; Bollène, 13,574; and Orange, 29,482.↩

- [4]visa, Lumières sur mairies brunes, nos. 1–9 (a book published by Syllepse and a series of texts available on the visa website, as well as many other articles of this network of “anti-fascist” trade unionists).↩

- [5]Marine Tondelier, Nouvelles du Front. La vie sous le Front National. Une élue de l’opposition raconte, Les Liens qui libèrent (2017).↩

- [6]To briefly explain the difference between modern national-populism and fascism, I can quote what Enzo Traverso writes about Trump: “He has no program…. He does not mobilize the masses, he attracts a public of atomized individuals, of impoverished and isolated consumers,” Les nouveaux visages du fascisme, Textuel (2017). Traverso prefers to use the word “postfascism” because, like most left-wing intellectuals today, he supports Latin American populists (Chavez, Morales), and he still wants to cling to the confused concept of the “people.” This notion has always been central to conservative, far-right and fascist thought because it had an ethnico-racial-cultural foundation and the left never succeeded in transforming it into an emancipatory concept, despite all its efforts.↩

- [7]In 2017, the National Front has 11 mayors out of 36,000; 62 departmental councillors out of 4,108, and in only 14 “départements” out of 100; 1,540 municipal councillors out of 536,500; 8 mps out of 577; 2 senators out of 348 and 24 meps out of 751. The absence, in France, of a proportional voting system explains the huge gap between the number of voters and the number of elected officials. Those on the left who struggle for a more democratic system are caught in a lethal contradiction, as the introduction of a proportional vote will only give a tremendous power to a party they denounce as “fascist.”↩

- [8]According to Christèle Marchand-Lagier (Le vote fn (DeBoek), 2017), in the south of France, one of the main reasons for the defeat of the right and the victory of the National Front was that it did not leave any room for young ambitious men or women.↩

- [9]The National Front’s sympathizers and voters express their opinions very frankly on this social network, often without hiding their real names and faces. They feel less and less ashamed of their political choices.↩

- [10]An anonymous Facebook account (“La Voie d’Hénin”) is specialized in personal attacks and nasty “jokes” against the opponents of the National Front.↩

- [11]Towards Muslims (as well as on the question of celebrating gay marriages), the National Front mayors do not have a unified policy: in Hénin-Beaumont, Steeve Briois praised the local Muslims and imam and agreed to let them build a new mosque; in Mantes and Fréjus, the National Front mayors are waging a legal battle to impede the construction of new mosques or prayer rooms. And in Béziers, Robert Mesnard (who is supported by the National Front but not a member) has found twisted means to attack Muslim food shops’ owners because they were opening late during the month of Ramadan.↩

- [12]Especially soccer, probably because it appeals to youth with North African and Sub-Saharan backgrounds. This popular attraction does not fit with the National Front’s discreet ethnic cleansing policy. There are also other unofficial means to ethnically control the territory, as testified by the methods used by some mainstream right-wing mayors who want to seduce the National Front voters in the new peri-urban areas developing near important highways. These areas welcome a significant portion of Franco-French qualified workers and new petty bourgeois (executives, teachers, social workers, foremen, etc.): the mayors contact the real estate developers and the private owners who want to sell their farms or their houses and they try to push them not to sell (or rent) their properties to “non-European” buyers. For more details see: Violaine Girard, Le vote fn au village: Trajectoires de ménages populaires du périurbain, Editions du Croquant (2017).↩

- [13]Mainstream artists and (mainly Parisian) intellectuals generally don’t have a high opinion of French folklore and traditions. They are much more interested in “world culture.” Therefore, they give an opportunity to the National Front to appear as a courageous defender of “Gallic” popular culture and to defend the humble citizens of the provinces against the arrogant Parisian “elites.”↩

- [14]The caf (Caisse des Allocations Familiales) offers different services and benefits concerning nursery and daycare fees, education allowances, holidays, family allowances, pregnancy and housing benefits.↩

- [15]rsa means “Revenu de Solidarité active” (Active Solidarity Income). It offers supplementary benefits to people who are jobless: 536 euros for one person; for a parent with one child (805 euros), two children (966 euros), etc. For a couple: 689 euros; with one child (919 euros) and 2 children (1,148 euros), etc. Obviously, these benefits are “given” to people who have already worked and depend on other resources.↩

- [16]Founded in 1985 by a very popular stand-up comedian and actor, this ngo mainly provides free meals and has become an important institution given the dramatic rise of poverty in France.↩

- [17]This fantasy was already defended by the neo-fascist group Europe Action in 1966 which compared the Algerian immigration to a “slow genocide” and defended what it called “biological realism,” therefore supporting South African apartheid and racial segregation in the United States. This grouplet was created in 1963 by several former French ss, pro-Nazi collaborators and young far-right intellectuals (the most famous being Alain de Benoist who later founded the grece and dominated the French “New Right.” He has influenced all right-wing and far-right parties since then, but he claims not to be racist anymore). Most of these leading militants, including the neo-fascist theoretician Dominique Venner, joined the National Front later, where they played an important role.↩

- [18]This idea of a “foreign demographic invasion” is as old as migrations in France and has always been central to parliamentary politics. Marine Le Pen denounced “a genuine clandestine project favoring a massive settlement of migrants.” See my article: “French working class, migrants, racism and the building of French national ideology.”↩

- [19]As underlined by Dominique Reynié (“Le tournant ethnosocialiste du Front national,” Etudes no. 11, 2011), the National Front does not appeal only to the traditional petty bourgeoisie of artisans, shopkeepers, and small bosses; it tries to build an interclass alliance including all wage-earners of the public and private sectors, promoting reindustrialisation, a strong state which will control and fight globalization to defend the “French social model.” It praises the French welfare state (which it always criticized during its first thirty years of existence, when it hailed Thatcher and Reagan) against the World Bank, the imf and the eu.↩

- [20]Actually, the National Front has always mixed a xenophobic rhetoric with a social one, as testified by this speech of Le Pen in 1974: “The French people give a fraternal hand to the foreign workers who are serious and diligent, useful to our economy, who respect our laws, our morals, our civilization. But they can’t let France be colonized, exploited and terrorized” (quoted in Valérie Igounet, Les Français d’abord, slogans et viralité du discours Front National, Inculte/Dernière marge (2017), p. 76). And, if we go back earlier, to the nineteenth century, the nationalist and anti-Semitic political thinker Maurice Barrès already wanted to protect the French workers against the foreign labor force and invented in 1898 the concept of “nationalist socialism.”↩

- [21]Already in 1987, the National Front printed a poster reproducing a quotation from a Hezbollah leader, Hussein Moussawi: “Inch Allah, within twenty years France will certainly be an Islamic Republic.” Although the quotation was not exact (Moussawi actually declared: “Maybe your generation will not live under an Islamic Republic in France, but it will certainly be the case for your sons and grandsons,” the meaning was the same. Nevertheless, for twenty years this line disappeared from the National Front’s propaganda and only massively reappeared in 2009 after the referendum about minarets in Switzerland.↩

- [22]Dans la tête de Marine Le Pen, Solin/Actes Sud (2017), p. 140.↩

- [23]According to Marine Le Pen, the “European monster” is a “conglomerate under an American protectorate, the antechamber of a world global total State”; “the European Union wants to mold a new human being, with uniform tastes, cut off from his national culture,” “nomad, disposable, slave of the merchant social order”; it “weakens the family…, despises values such as effort, work, merit, courage and righteousness,” quoted in Michel Eltchaninoff, op. cit., pp. 78–79.↩

- [24]Here is the video, and the article itself is also useful because it describes how, in the département of the Bouches-du-Rhône, 38 out of 94 municipal councillors have left the National Front or moved to another town, thus also lost their elected responsibilities.↩

- [25]See my article “The sad farce of the ‘no’ victory.”↩

- [26]Migrants, foreigners or nationals with a foreign background are all mixed together in this common hatred.↩

- [27]Some historians compare the present National Front to the “Boulangist” movement. Georges Boulanger (1837–91) was a general who started his political career in 1886, supported by the monarchists, the Bonapartists, the nationalist leagues and part of the left in a context where the Republican institutions were in crisis, the politicians were considered as corrupt and the consequences of the French defeat against the German Empire in 1871 were still not accepted. This movement lasted only five years while the National Front has been active for 40 years in a context of economic crisis, mass unemployment, politico-financial scandals and parties which seem more and more incompetent and interchangeable.↩

- [28]Obviously, there are many bureaucrats in the European institutions, but most of the important decisions are not taken by a “Brussels” of fantasy, as the national-populists (and sometimes the radical left) claim, but by the prime ministers and economics and finance ministers of the 27 countries.↩

- [29]Nonna Mayer, “De Jean-Marie à Marine Le Pen: l’électorat du Front national a-t-il changé?” in Pascal Delwit (dir.), Le Front national. Mutations de l’extrême droite française (Editions de l’Université de Bruxelles), 2012, available online.↩

- [30]“Haut, bas, fragile: sociologies du populaire,” interview with Annie Collovald et Olivier Schwartz.↩

- [31]Valérie Igounet and Stéphane Wahnich, fn: une duperie politique, Cahiers du CRIF no. 39 (2015), available online.↩

- [32]This is also the opinion of Bernard Dolez and Annie Laurent (“Voix sans élus. Le vote Front national dans la région Nord-Pas-de-Calais,” in Pascal Delwit, op. cit.): “The National Front’s rhetoric focuses on the resentment and social anxieties of the categories which are threatened by downward social mobility. The feeling of being relegated to the periphery of the social space, or the threat of being soon relegated there, constitutes today one of the most powerful sources of the vote for the National Front.”↩

- [33]This region has 4 million inhabitants today and it sent five National Front deputies to the French Parliament in June 2017 (Marine Le Pen, Bruno Bilde, Sébastien Chenu, Ludovic Pajot, José Evrard). Traditionally it was an industrial region for textiles (it still has 25 percent of textile activities), metallurgy (16 percent) and transports (14 percent). The median standard of living (although not a significant indicator) is the lowest in France (17,700 euros per year, that is 2,000 euros less than the national one) and the progression of the gdp between 2000 and 2012 has been inferior (0.9 percent) to the national one (1.2 percent). Employment has diminished of 0.7 percent per year between 2008 and 2013, and all industrial sectors (especially metallurgy and chemistry, which have sacked 12,000 workers during this period) have been touched, apart from the energy sector that has been growing. This process has started a long time ago: Daniel Percheron, a “Socialist” senator, already noted in 1988 that between 1975 and 1986, 195,000 jobs had “disappeared” in the regional industry. According to a report recently written for the new region Picardie-Nord-Pas-de-Calais executive, there were 850,000 wage earners in the industrial sector in 1965 and only 280,000 in 2014. Today most interesting jobs require two years of studies after high school, the ability to speak at least two languages, and engineers’ and technicians’ diplomas. In this region, as everywhere else in France, French bosses don’t want to invest a cent in apprenticeship and internal training…but complain that they can’t find workers with “adequate” qualifications!↩

- [34]And these long-term consequences will be even more devastating because the French left uses dubious concepts like “whites” or “racialized”—even in Les classes populaires et le fn. Explication de votes (coll.), Editions du Croquant, 2017, which is an excellent book about the relationships between class divisions and the votes for the National Front.↩

- [35]One “alternative” media, Paris Luttes Info, during the 2017 presidential campaign, published an article showing that in several electoral districts having barracks where the “gendarmes mobiles” and “gardes républicains” are living, the number of votes for the National Front is much higher than in the other districts of the same town (from 30 to 100 percent more). That may not be a coincidence… And this has been also proved in a study of the vote for the National Front in Corsica, where soldiers and their families are stationed in certain districts and where the vote for Le Pen’s party is exceptionally high.↩

- [36]This myth of the National Front as the “biggest workers’ party in France” was launched by Jean-Marie Le Pen in 1995. And he even went as far as to “greet the long struggle of the workers and trade unions for more justice, more security, and more freedom in the workplaces” in 1996 (Valérie Igounet, Les Français d’abord, op. cit., p. 136).↩

- [37]Discipline is a major aspect of the National Front ideology, as evidenced by this internal document: “Our movement is an army. Exactly like in army on the battlefield, we can only be efficient if each of us accomplishes his mission, respects and executes the orders given to him so that the whole maneuver will be perfectly performed…. The militant is a political soldier; like any soldier, for the general benefit of all, he must respect a set of rules to ensure the triumph of our national ideal,” V. Igounet, Les Français d’abord, p. 43.↩

- [38]Agnes Marion, Pour le Front National, Le Progrès, February 9, 2017.↩

- [39]The National Front website greets a newly-wed leader and his wife with this very clear Biblical saying: “Be fruitful and multiply.”↩