First, I want to offer my condolences to Sharon and Loren’s family. The loss we all feel is hard enough, but of a different order. And thanks to John Garvey for staying close to Loren and keeping us in touch during the last difficult period, and for gathering us here today. And for including me.

I met Loren in the ’80s, in his Cambridge days, through politics and through books. Loren often signed his messages “your friend and comrade,” and that’s exactly how I felt about him. I’d see him often at the Harvard Bookstore where I worked; I recognized him for what he was: a first-class Marxist intellectual with wide-ranging – omnivorous – interests – and expertise, who also reacted with strong emotion to works and people of depth. I was at the time in one corner of the Trotskyist movement, while Loren oriented to his own interpretation of communism, I think you can say. Arguments ensued, of course, but unusually, they grew more interesting rather than less.

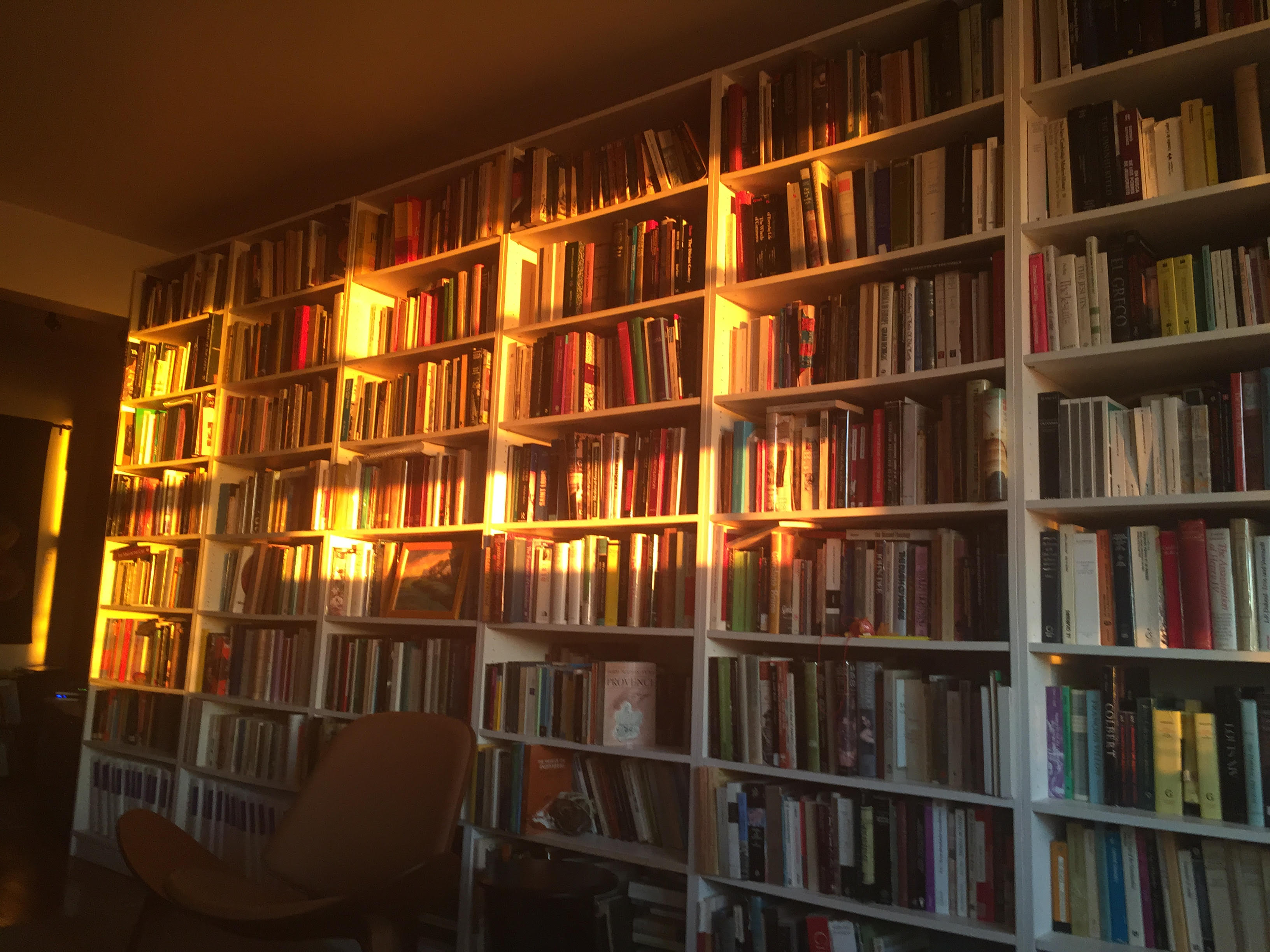

At one point, Loren had to move out of his tiny Cambridgeport apartment, where the books were so ubiquitous, they literally supported his bed and they topped the refrigerator. They were huddled like bats in a cave. He’d rented a 24-foot U-Haul to drive the library to Berkeley, and he needed a couple of burly movers to help. What he got was myself, weighing in at 135 lbs. (~60 Kilo), and Michael Mack, his neighbor and poet. It took a while, but we did it, and Loren, in a characteristic gesture, took us to the Sunset Grill, a Portuguese diner in East Cambridge that proved to be the best of its kind I’ve ever found. It’s now gone, like so much of the neighborhood charm of Cambridge. So much for the books in their physical presence.

Loren was kind of a model for me. I am occasionally, at seminars, forced to introduce myself as an “independent scholar.” I blush when I think of what kind of unaffiliated academic Loren was. He steadily dealt with the most important issues for the left over a period of several decades. I still think his Vanguard of Retrogression is an excellent take-down of the trendy exits from Marxism that characterized the 1980s, a model for a critique of intellectual backsliding.

He was a genuine non-party intellectual, but actively organizing the basis for future organization as he saw it. Similar in some ways to Trotsky in the down-period after 1905. His polemics against the recent Maoist revival were sharp and to the point. He had so much experience and knowledge, I urged him to write his memoirs. He balked, thinking that had not lived through revolutionary times. I think of memoir as being a Homeric moment, when the oral tradition is written down; it a loss that we won’t have that side of Loren’s life, present company excepted!

When I read his polemics at their best, I think of what Trotsky wrote of Marx and Engels’ correspondence: “there is so much instruction, so much mental freshness and mountain air! They always lived on the heights.”

He had no illusions about our time, though he followed every movement of workers. He would reread Victor Serge, whose tragic optimism seemed to be a compass for his heart, as it is for mine. He felt a similar affinity for Melville, his scope and searching. And like Serge and Melville, Loren was a true internationalist. Loren was also an exemplar of what Isaac Deutscher termed the “non-Jewish Jew”, like Rosa Luxemburg, who took the best of the Jewish and Enlightenment traditions in the service of humanity.

Byron wrote: “there are only two sentiments of which I am constant: a hatred of cant and a love of liberty.” Loren was tireless in his commitment until he could no longer function. I will miss our conversations and will have to rely on the works he left us.

Farewell, friend and comrade! Long live socialism and the memory of those who have fought for it!