“Are riots a war of the poor against the poor?” The question puts one in mind of a Thunderdome circa a post-apocalyptic 2014, or even a Superdome circa a post-hurricane 2005. Both were and are fictions.

The answer is no. US riots since World War II have typically been black and Latino proletarian responses to racial oppression, and far from these riots indicating anything like a war of proletarians versus proletarians, or even the poor against the poor, these riots are actually brief moments of respite from the otherwise constant and brutal war of the ruling class, in all its entrepreneurial embodiments, upon them.

But the narrative that gives rise to the question usually starts with “they’re burning down their own neighborhoods,” or turning over neighbors’ cars, or destroying neighborhood businesses, or even, like I heard around the rather tame Occupy LA protests, “they’re hurting the people they want to help! What about the small business owners in the area, whose foot traffic is interrupted?”

You can even find people close to riots saying such things. Rodney “Why Can’t We Be Friends?” King, for example.[1] Or one black man from Baltimore recently, who, out in the streets, surrounded by rioters, yelled:

It be “fuck the police,” but that’s on our block though, brah! Now, we’re destroying our homes! Now, we’re destroying our community! For what!?… For what? If you wanna protest, if you wanna make a voice, if you wanna stand up, do it the right way! Get your local legislator, get your religious leaders, and let’s sit down and talk about this![2]

I doubt he owns any of the homes he is worried about. I doubt he owns a business nearby. I wager that he rents an apartment and holds a precarious job. If he went to college to learn this line, he has student debt as well.

So, we can laugh at this guy asserting ownership of the “community,” but what else is he going to say? What is the authentic voice of a riot? Some passersby, perhaps on their way to riot, responded simply, “Fuck the police!” True. But is that it? Where is the authentic defense of a riot to be read? Because it certainly won’t be heard, because rioters don’t stop for interviews.[3] I don’t think rioters write essays, either, for that matter. And the reigning ideology is such that there’s not many concepts ready to hand for the cogent expression of the situation that results in a riot. The riot, for all its expressiveness, is actually discursively mute. It doesn’t say anything.

For this reason, it is not hard to imagine even an active rioter in Ferguson or Baltimore, while taking a breather, saying something similar, perhaps not in the same words, but still, expressing something like this sort of apology for the outburst of anger, and perhaps even a sadness that things had to come to this pass, as they struggle and reach for a way to place the events in some positive, pro-community light. What they find close to hand is the above narrative of legal reform and redress, and then, not much further, the well-worn bag of black-nationalist tricks, which easily frames the events, the anger, the sadness and the frustration, and even accounts for the feeling that nothing has changed, the fear that nothing will change, and the dawning realization that business will, sooner rather than later, go back to normal.

But not before the Nation of Islam shows up to get the street gangs to hold hands and cordon off black-owned small businesses, shielding them from the righteous albeit misguided anger of the crowd, because that’s the real way to strengthen the community. In the United States, these gangs are the only social force remotely capable producing anything like “war of the poor against the poor,” but we see that in Baltimore, instead of exploiting the mayhem to go to war with one another, or with ethnic rivals, or on other ethnic populations, or on the populace in general, there are reports of newly-truced Bloods, Crips, and Black Geurilla Family gang members protecting black-owned businesses and directing rioters to Chinese and Arab-owned businesses instead.[4]

Next the mainline preachers and elected officials come in and start talking about healings and feelings. The “peaceful” everyday life they and the gangs seek to restore is the real war, and that peace is enforced with threats, not just of unemployment, homelessness, or police attention, but extra-legal violence as well.

I’d like to outline a little history of how this peace is imposed and managed, and of what it consists where riots and street gangs—the likeliest vectors of such a bellum pauperum contra pauperes—are concerned.

Los Angeles, 1992

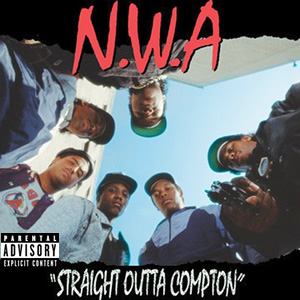

I was born in South Central, Los Angeles, at 56th and Main, three blocks north of Slauson, but moved away to Houston, Texas, in 1982 at the age of eight. My little brother and I spent two summers here (I moved back in 2009 after 11 years in New York City) in Los Angeles with my grandmother and uncle, in 1987 and 1988. There wasn’t much notable about 1987, but two things jump out about 1988: NWA’s first album and the evening news.

Forgive me if this sounds silly 27 years later, but Straight Outta Compton sounded exactly, precisely, like street thugs on wax. Exactly like the guys who, when my teenaged uncle saw a group of them up the block, would make us walk up another block to avoid them, to take the next street to where we were going. We had done this before I moved away, and we did it many times in 1987 and 1988. These were guys who would “sweat” you for no good reason, maybe rob you just for kicks, maybe hit you, maybe not. Stop you, block your passage, and interrogate you merely for walking around your neighborhood. That should sound familiar. Straight Outta Compton was both frightening—as in producing a sense of unease and fear—and exciting, but it was tolerable only in small doses. The evening news, on the other hand, was just plain frightening. I started counting: every night there were at least two dead young black men, victims of gang shootings. The news always chose terrible pictures of these guys, too. Never their yearbook photos, but always their worst mug shots. I stopped counting, and my brother and I took the Greyhound bus back to Houston.

Huey Newton was killed in Oakland, California, in August 1989 while buying cocaine from a member of the Black Guerilla Family, a onetime black-power organization founded by George Jackson, W.L. Nolen, and James Carr, in Soledad State Prison about 20 miles southeast of Monterey, California. In 1989, Louis Farrakhan, head of the black nationalist Nation of Islam, began a series of “Stop the Killing” lectures in Washington, Chicago, Detroit, and Los Angeles, among other places, as a result of the violence accompanying the crack epidemic. Farrakhan made it to Los Angeles in October 1989.[5] Several Watts gang leaders, themselves already eager for a change on the streets, went to see him. After the talk, Jim Brown, the great former Cleveland Browns running back, actor, and activist, invited some of these leaders back to his home to discuss peace options. He founded the Amer-I-Can gang-intervention organization shortly thereafter, and continued holding such meetings.

It took 3 more years for them to come to terms. On April 29, 1992, the day before the outbreak of the Rodney King riots, Jim Brown held the final set of peace talks between those Watts Crips and Bloods factions, and they sealed the deal.[6] The truce movement started there, and there were gang summits across the country, in Cleveland, Minneapolis–St. Paul, Chicago, and Kansas City. The rest of Los Angeles’s gangs were declaring truces before a year had passed.

Los Angeles has never been the same, for better and for worse. The outrageous levels of street violence have ceased, even though the treaty has been torn and tattered for years now, and is supposedly entirely defunct. From what I understand, the Mexican cartels supply everyone these days, and the street gangs are mostly retailers. In Los Angeles, the turf is already divided, so there’s no need for competition.

The LA riots were hardly a race war, either, neither among blacks and Latinos nor them against whites or Asians. The notorious black-Korean conflict was much more about the way petit-bourgeois shopkeepers treat their customers, who often have no other choices, given slum geography and all that.[7]

Besides that, the riot didn’t extend north past Koreatown into areas where whites would have felt themselves under attack. Just more than half of all arrests made during the riots were Latinos,[8] and eyewitnesses say that everyone, blacks, Latinos, and whites, was rioting together.[9] That only makes sense, because blacks and Latinos live literally next door to one another throughout South Central, and now South Central has more Latinos than blacks.[10]

During those 1992 riots, my family’s former pastor, Reverend Cecil “Chip” Murray of the First African Methodist Episcopal (FAME) Church north of Leimert Park, near Western and Adams, took the lead among community leaders, including first black Mayor Tom Bradley, in spinning the 1992 riots in the manner I spoke of above. The first night of the riots, more than 100 men of the church, led by Murray, formed a blockade against rioters trying to prevent firemen from putting out fires. His church was a charity center, providing temporary shelter and food aid, and he quickly established the “Renaissance Center”—a picture-perfect model of a particular type of black church organization that has spread across the country—with a $1,000,000 donation from the Disney Corporation, after a meeting with Michael Eisner.[11]

The Renaissance Center functions mostly as an informational center, pointing people in the direction they need to go for help with job training, public assistance, education, and the like. It is a nexus of NGO, non-profit, and private charity efforts.

In the meantime, the healing on offer that May and June of 1992 was a $500M House bill for loans and FEMA assistance to small businesses and homeowners damaged in the riots and in Chicago (a tunnel collapsed in Chicago, letting the river into downtown). The Senate (!) added another $1.5B in social spending nationwide, namely $700M for summer jobs and $250M for Head Start early-childhood education, $250M for summer school, and $250M for Bush’s pre-existing and ill-named “weed and seed” youth-intervention crime-prevention programs, neither specific to LA or Chicago, but nationwide,[12] because “there’s no sentiment in rural and suburban America in sending more money to inner-city mayors.”[13] One House Republican blamed Chicago for the flood, because the local government didn’t fix the wall between the tunnel and the river when they should have, and therefore they didn’t deserve help. Bush started talking about vetoing the $2B bill,[14] and Blue Dog House Democrats opposed it, too, because a balanced-budget amendment to the United States Constitution was under discussion and they wanted to look austere and punishing, so other House Democrats put together a $1B compromise that removed the Head Start and youth-intervention money, and reduced the summer jobs money.[15]

At the end of the day, in June 1992, the Congress and president finally approved the additional $170M in Small Business Administration loans for disaster recovery, $70M in new normal SBA loan money, $300M in additional general FEMA funds, and $500M in summer job money, of which only $100M was earmarked for the 75 largest cities, and the remaining $400M was for nationwide disbursal, because the Blue Dog Democrats wanted summer jobs for rural areas instead of the initially targeted city areas. The Senate also agreed that any applications for aid should be delayed anywhere from 90 to 180 days, because 90 days is the speedy-trial deadline in California, and sometimes judges give prosecutors 180 days to bring a case to trial, and it shouldn’t be possible for any rioter to receive assistance.[16]

That was the only federal aid to Los Angeles after the 1992 riots, and none of it was for Los Angeles per se. Dan Quayle told Tom Bradley to sell LAX if he needed more money.[17]

The June aid package was understood to be a compromise, with the understanding that Congress would go back to the drawing board to come up with a comprehensive urban aid plan, the centerpiece of which would be George Bush’s initiative to establish 50 enterprise zones—half rural, half urban—with capital-gains tax writeoffs and other such benefits. Jack Kemp also wanted to allow public-housing residents to buy their apartments, and Bush wanted school-choice vouchers.

The single bit of aid that went to Los Angeles per se was given through another channel, in October 1992: $3M in weed-and-seed money from the Justice Department, which went to pay LAPD overtime and to fund a special anti-gang and anti-riot law-enforcement task force.[18] Meanwhile, the enterprise-zone bill that Congress had been working on all summer had been expanded to include tax cuts for real estate speculation and IRA deductions, and for boats, planes, furs, and jewelry. It also increased taxes by eliminating deductions for club membership dues.[19] The cost of this “urban reform” bill had increased to $37B, most of which had nothing to do with alleviating urban poverty, and most of which would only increase it. Bush vetoed this Tax Fairness and Economic Growth Act on November 4, 1992, the day after he lost the election to Clinton.[20]

That’s not the end of the story. In May 1993, Clinton ran with Bush’s enterprise-zone idea, and sent his Housing and Urban Development Secretary Henry Cisneros, former mayor of San Antonio, to Los Angeles to promote this plan, in which LA would be the largest of 10 urban “empowerment zones,” receiving up to $100M. Cisneros held a press conference at, of course, First AME church, with Reverend Cecil “Chip” Murray at his side.[21] It took Clinton until August to get this through Congress, and it finally created 9 “empowerment zones,” three of which were rural, and 95 “enterprise communities,” of which 30 were rural. And LA didn’t even get an empowerment zone.[22] Among the six cities that did—New York, Chicago, Baltimore, Atlanta, Detroit, and Camden/Philadelphia[23]—the results these 21 years later speak for themselves.

In an interview after the George Zimmerman verdict, Reverend “Chip” Murray was wistful, saying that we’ve been here before, and that healing will take “crucial systemic changes.” When asked what sort of systemic changes, the reverend replied:

Black America is a consumer economy… It isn’t enough any longer for any Americans, particularly African Americans, to say, “Give them a fish.” It isn’t enough to say, “Teach them how to fish.” Now it’s enough to say, “They must learn how to own the pond.”[24]

So we see that 23 years ago, at the beginning of the mild recovery from the S&L recession, at the beginning of the “Third Way” “neoliberal” consolidation, before the “new economy,” urban reform policy consisted of little more than charity, police and tax cuts for small business. But the gang truce held, and the murder rate decreased, because the Bloods and Crips themselves decided to do that, for their own reasons. They seem to have been sincere. I have left out mention thus far of the Mexican Mafia and Mara Salvatrucha 13, and the other “Sureños 13”[25]/“Eme”[26] gangs, but I should mention that the 1992 truce extended to these Latino gangs as well.

In 1992, Peter “Sana” Ojeda, the imprisoned leader of the Orange County Mexican Mafia, began promoting a truce among the warring factions of the Eme gangs. The upshot of the public peace talks held in Elysian Park in downtown Los Angeles in September 1993, which were attended by police and media, was a new tax on drug dealers operating in Latino neighborhoods, and a ban on drive-by shootings. A ban on drive-by shootings. In this manner, the Eme in fact consolidated Latino narcotics traffic in Southern California, increasing the revenues of everyone involved, and ceased bringing heat down upon their heads with “senseless” violence.[27] In the intervening “peaceful” years, as they have grown more powerful as a result of their control of the drug trade, and as the demographic balance of blacks to Latinos has changed, only now have the allied Eme gangs become explicitly racist, sometimes attempting something like ethnic cleansing of neighborhoods they consider their own.[28] I don’t want to exaggerate this, but it is a real phenomenon, and it began after the riots, under the truce, during normal business operation.

Chicago, 1967

Things played out a little differently under the New Deal/Great Society regime. But the differences only highlight the similarities.

The Woodlawn, Chicago, Blackstone Rangers were formed by Jeff Fort and Eugene Hairston in the early 1960s. After two years of riots, the Johnson Administration wanted to get to the bottom of things by the summer of 1967. The Kerner Commission was established to do so. Keep in mind, this administration had founded the Office of Economic Opportunity way back in 1964, before any of this wave of riots. Huey Newton and Bobby Seale used an OEO grant to found the Black Panther Party in 1967. Meanwhile, the Blackstone Rangers allied with the East Side Devil’s Disciples to keep order in Chicago that summer, during which 159 riots burned throughout the country. So, although they were a street gang, they were often praised, and their legitimacy was based on this riot suppression on the South Side of Chicago in 1967.

The Woodlawn Organization, an organization close to the Blackstone Rangers, was very similar to the FAME Renaissance Center, and many church organizations like it. It was a community organization founded by liberal clergy, black and white, from the white First Presbyterian Church and the black Apostolic Church of God in Woodlawn, Chicago, with input from the nonprofit Chicago Urban League, and the altruistic Xerox and Arthur Andersen corporations. There was also a police liason. This organization was on the frontlines of Johnson’s War on Poverty, and that June 1967, it received a $1M Office of Economic Opportunity grant meant to “utilize the existing gang structure…as a means of encouraging youth…to become involved in pre-employment orientation.”[29] One of the conditions was that the Rangers and the Devil’s Disciples maintain the truce for 8 months.[30] Fort and Hairston were put on the payroll as the leaders of the project. Rangers leadership also broke up a black power rally that September, further cementing their public image.[31]

While the Rangers were in talks with the Woodlawn Organization over the future of the organization and the projects it should undertake, they were engaged in their own business as well. Fort and Hairston seemed to be using money from the organization to finance their entry into the local narcotics trade, which required that they buy lots of weapons to kill their competitors, weapons which they seemed to have hid in the basement of the First Presbyterian Church. Job training money for youth appeared to be diverted instead to hiring youth for this other type of summer job, and three youths were arrested for the murder of a local drug dealer, allegedly on Hairston’s orders.

Hairston and Fort went to jail on two separate murder charges: Hairston for the drug dealer, and Fort for killing a rival Devil’s Disciple, thus breaking the truce. There were Senate committee hearings on the Woodlawn Organization in June 1968.[32] The president of the organization, Reverend Arthur Brazier of the Apostolic Church, vehemently denied the weapons and embezzlement story. Jeff Fort refused to testify, was charged with contempt, and didn’t get out of jail until December 1968.

A former Ranger, meanwhile, testified to the truth of the guns, embezzlement, and murder charges, and explained that the money had enabled the Rangers to forcibly draft local youth, because they could afford more weapons to back up their threats. This former Ranger also testified that the gang had formed a volunteer police auxiliary, which of course offered up rival gang members to the Chicago PD, while clearing the neighborhoods of non-Ranger criminal elements. The influx of money allowed the Rangers to increase their taxation of local businesses, and during the riots of 1968, after quickly re-establishing their truce with the Devil’s Disciples, they joined forces with the Disciples to sell these same exploited businesses Ranger-backed protection signs for $50.[33] They ran these operations from their riot-control center in the basement of the First Presbyterian Church, the one with the arsenal.

Sometime in 1968, the Rangers changed their name to the Black P. Stone Nation, and opened a community center from which they ran an FM station and hosted a University of Chicago student-radio show. They put on music events covered in the local press (the “Blackstone Singers”), and they opened a restaurant with a grant from another community organization. In 1971, the Rangers sent several members to an entrepreneurship training program run by the local Chicago Small Businessmen’s Association, and rented a building from the Humble Oil Company for $1 a year, which would serve as the headquarters of P Stone enterprises. The Westinghouse Corporation donated a laundromat’s worth of washing and drying equipment for them to open a business with. They received two car washes, and a piece of a liquor store Sammy Davis, Jr. owned. Jeff Fort was invited to Nixon’s inaugural ball in 1969, but he sent Mickey Cogwell and another of the “Main 21” leadership instead.[34]

Cogwell and Fort went to prison in 1972 for charges stemming from the original OEO/Woodlawn fiasco, and when Fort got out in 1976, he had converted to Islam. He changed the name of the Black P. Stone Nation to the El Rukn Tribe of the Moorish Science Temple. Cogwell got out in 1976 and started organizing McDonald’s fast-food workers, attempting to give the former P Stone Nation a political orientation. In this, he was interfering with the profits of Chicago organized crime, and Fort either couldn’t protect him, or decided to kill Cogwell himself in 1977.[35]

Fort was heavily involved in those years with Jesse Jackson’s brother, Noah Robinson, a front-man for white-owned businesses bidding for affirmative-action contracts in Chicago,[36] and he was convicted in the late 1980s of connecting Fort and the Rukns to cocaine and heroin wholesalers, and a host of other horrible crimes.[37]

In 1983, Fort was convicted again on narcotics charges, and sent to Leavenworth Federal Penitentiary. Meanwhile, Louis Farrakhan, a Chicago resident, had hired some of the El Rukn tribe as bodyguards—he called them his “Angels of Death,” and invited them on stage with him in his 1985 Savior’s Day address, to introduce them to Muammar Qaddafi, telecast live on screen from Libya.[38] Qaddafi had loaned the original Nation of Islam $3M in 1971 to buy the Greek Orthodox church that became Mosque Maryam, its national headquarters,[39] and he had recently made Farrakhan another $5M loan to start a line of black beauty products called Clean ’n’ Fresh. Qaddafi, in his telecast, asked Farrakhan and his Angels of Death to go to war for him against the United States government. Farrakhan meekly refused, but thanked him for his generosity. Fort heard all about this in prison, and began talking to his lieutenants about getting in on this Qaddafi thing. The FBI was monitoring his phone calls, of course, and they set up a sting operation in which they enticed several Rukns with the promise of selling the Rukns a set of anti-tank missiles with which to attack US government facilities.[40] Fort and others were convicted on these terrorism charges. The US state has not forgotten the lessons it learned there, and it goes around today entrapping gullible and misguided black youth into harebained jihadist schemes.

So, in the heyday of the American Dream, one urban reform policy was to finance community organizations, some of which were criminal outfits with retrograde politics, in the hope that they would foster legitimate business organizations, and thereby create “jobs in the community.” This policy required, sought out, and legitimized the “poverty pimp”: a caricature, to be sure, but a real character—in the case of this Chicago story, the cast includes the Reverend Arthur Brazier, the Reverend Jesse Jackson, and his Wharton grad brother Noah Robinson. The “poverty pimp” is one particularly corruptible instance of the “black leadership class,” ye olde talented tenth, always ready to collect their tithe, and I think Jesse Jackson is the most infamous of these. There should be no doubt about how rioters feel about these folks today, after Ferguson, where they chased Jackson away.

Chicago Today

Today, there is no urban reform policy on offer. We may have another “conversation” about “race,” but there’s really just the re-imposition of daily life and its “peace.” The content of this peace can be seen on the blood-soaked streets of the South Side of Chicago, where Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman’s Sinaloa cartel supplies the Gangster Disciples with narcotics. The Gangster Disciples are part of the Disciple Nation, of which the Devil’s Disciples, mentioned above, were a part. The founders were Larry Hoover and David Barksdale, both from Mississippi, David Barksdale hailing from around Meridian, from which my father’s family comes, which indicates that we share ancestral slaveowners.

The Sinaloa Cartel has worked for years, since the mid-2000s, to establish monopoly control over the narcotics trade in the Midwest.[41] Guzman never would have had the opportunity to enter this market without the help of Bill Clinton, whose Housing and Urban Development Department set in motion the demolition of public housing nationwide, under its HOPE VI plan,[42] a gentrification/privatization scheme whose rationale was that distributed poverty is better than concentrated poverty.[43] One of Barack Obama’s senior advisers, Valerie Jarret, was a Chicago developer who benefited from these “reforms”: her company, Habitat, had managed several public-housing projects, and received contracts to build and manage the replacement low-income housing.[44] The company was appointed to oversee the desegregation of the projects in 1987[45]— “desegregation” being a codeword for dispersal, e.g., urban renewal, i.e., Negro removal.

By 1993, with subsidies from the Clinton Administration’s HOPE VI program, the public housing units began to be destroyed. And by 2000 he’d put in place something called The Plan for Transformation. It targeted tens of thousands of remaining units. With this proviso: That African Americans had to get 50 percent of the action—white developers had to have black partners; there had to be black contractors. And Daley chose African Americans—as his top administrators and planners for the clearances, demolition and re-settlement. African Americans were prominent in developing and rehabbing the new housing for the refugees from the demolished projects—who were re-settled in communities to the south like Englewood, Roseland and Harvey. Altogether the Plan for Transformation involved the largest demolition of public housing in American history, affecting about 45,000 people—in neighborhoods where eight of the 20 poorest census tracts in the United States were located.

But what does this all have to do with Obama? Just this: the area demolished included the communities that Obama represented as a state senator; and the top black administrators, developers and planners were people like Valerie Jarrett—who served as a member of the Chicago Planning Commission. And Martin Nesbitt who became head of the CHA. Nesbitt serves as Obama campaign finance treasurer; Jarrett as co-chair of the Transition Team. The other co-chair is William Daley, the Mayor’s brother and the Midwest chair of JP Morgan Chase—an institution deeply involved in the transformation of inner-city neighborhoods through its support for—what financial institutions call “neighborhood revitalization” and neighborhood activists call gentrification.[46]

The destruction of the projects did indeed distribute the misery, as intended, flinging far and wide the drug-dealing gangs, who had focused their activities within certain projects. The Mickey Cobras (named, yes, for the slain Mickey Cogwell) and the Gangster Disciples used to share the Robert Taylor Homes, for instance. These reforms threw the gangs into disarray, giving Guzman the opening he needed to establish wholesale monopoly over Chicago narcotics wholesaling, blasting his route clear from Juarez/El Paso straight up through the Midwest to Chicago.[47] Having done so, he increased the prices. Which means that the gangs are forced to fight one another for territory, because the price is taking more of their profit margin, and the gangs can buy from no one else. The level of violence is not as bad as during the crack epidemic, but it is more concentrated geographically.[48] The austerity politics of Clinton/Obama-style Democrat Rahm Emanuel concentrate the violence further by closing schools, thereby forcing students from rival territories to walk through foreign gang territories.[49]

So…

This peacetime activity is the real war on the poor. And it’s not the poor prosecuting it. Far from being Mad Max–style wild warriors, gangs form truces during riots for the same reason the state sends the National Guard: To defend themselves and protect their situation, and to reimpose normal everyday competition and exploitation. Whether the competition is that of atomized workaday folks against “illegal” immigrants or blacks or foreigners “taking jobs” and other social resources, or that of armed competitors in the drug trade, this is the social peace from which riots break, and which they seek, noisily, destructively, yet non-discursively, to abolish.

- [1]I know that’s not what he said. It’s the name of a 1975 War album, which I thought more thematic!↩

- [2]Michael Morris, “Concerned Local Blasts Violent Protesters in Baltimore: ‘This Is Not How You Stage a Protest,’ ” CNS News, April 28, 2015.↩

- [3]That’s not entirely true. Watch some of the YouTube videos from Ferguson. But you will note that these are expressions of anger and hostility, and not about the riot per se, which proceeds as a fact.↩

- [4]Ron Nixon, “Rival Gang Members Unite,” New York Times, April 28, 2015.↩

- [5]Charisse Jones, “Farrakhan to Speak to 900 Gang Leaders to ‘Stop the Killing,’ ” LA Times, October 6, 1989.↩

- [6]Frank Stoltze, “Forget the LA Riots—historic 1992 Watts gang truce was the big news,” KPCC, Southern California Public Radio, April 28, 2012.↩

- [7]After the riots, Von’s supermarkets, for instance, promised and failed to build twelve new grocery stores in South Central. See Josh Sides, “20 Years Later: Legacies of the Los Angeles Riots,” Places Journal, April 2012.↩

- [8]Paul Lieberman, “51 percent of Riot Arrests Were Latino, Study Says: Unrest: RAND analysis of court cases finds they were mostly young men. The figures are open to many interpretations, experts note,” LA Times, June 18, 1992.↩

- [9]“ ‘It was rich versus poor,’ Brown [a white man] says. ‘They came right up La Brea, and every race was looting. It was poor people, poor people who needed things, taking furniture and electronics. It started out about police brutality, and then it turned into a free-for-all,’ ” quoted in Ted Soqui, LA Riots, an LA Weekly microsite.↩

- [10]The ratio is about 60:40 Latino to black: see Josh Sides, Places Journal.↩

- [11]Varun Soni, “The Los Angeles Riots 20 Years Later: An Interview with the Rev. Dr. Cecil ‘Chip’ Murray Of F.A.M.E.,” Huffington Post, April 16, 2012.↩

- [12]James Gerstenzang and Art Pine, “Panel Adds $1.45 Billion for Urban Aid: Riots: Senators give bipartisan support to more funds for social programs nationwide. They also back disaster assistance for Los Angeles,” LA Times, May 20, 1992.↩

- [13]Newt Gingrich as quoted in “Emergency Aid for Cities Tops $1 Billion,” CQ Almanac, 1992.↩

- [14]Art Pine, “Senate takes up $1.4 billion urban aid bill that Bush calls ‘not acceptable,’ ” Baltimore Sun, May 21, 1992.↩

- [15]William J. Eaton, “House Readies Compromise $1-Billion Urban Aid Bill: Congress: Bush is expected to sign the measure assisting L.A. riot victims, creating 360,000 summer jobs for youth,” LA Times, June 18, 1992. The title of this article implied that there would be 360,000 summer jobs in Los Angeles, which was not true.↩

- [16]CQ Almanac, 1992.↩

- [17]Jim McGee, “Kemp Rejects the Idea of LA Airport Sale,” Washington Post, May 25, 1992.↩

- [18]Somini Sengupta, “$3-Million Grant to Help Authorities in Gang Crackdown: Crime: Funds will go to multi-agency task force and LAPD. Critics say government should emphasize education and jobs instead of law enforcement,” LA Times, October 10, 1992.↩

- [19]Art Pine, “Bush to Veto Urban Aid, Tax Bill, White House Says,” LA Times, October 24, 1992.↩

- [20]“Bush Vetoes Year’s Second Tax Bill,” CQ Almanac, 1992.↩

- [21]Carla Rivera, “$100-Million Riot Recovery Aid Studied: Rebuilding: HUD Secretary Cisneros says L.A. could become Clinton Administration’s testing ground for many of its urban programs. City might be largest of 10 ‘empowerment zones,’ ” LA Times, May 27, 1993.↩

- [22]Ronald Brownstein and John Schwada, “Clinton Seeks Larger Aid Program to Include L.A.: Grants: City is left off list of ‘empowerment zone’ recipients. Valley had requested $700,000 for six projects,” LA Times, December 21, 1994.↩

- [23]“Clinton… $3.5 Billion for Empowerment Zones,” Time, December 21, 1994.↩

- [24]Catherine Green, “L.A. Riots: Rev. Cecil Murray Sees Progress In Inclusive Society,” Neon Tommy, Annenberg Ditigal News, April 24, 2012.↩

- [25]Sureños means “southern,” and the southern means Southern California. It’s an umbrella term, and is applied to and claimed by all the gangs that are now affiliated with the Mexican Mafia, many of which had their origin back with the Mexican Mafia in the California prison system in the 1960s and 1970s. The 13 is for the thirteenth letter of the alphabet, “M,” for Mafia, e.g., the Mexican Mafia.↩

- [26]“Eme” is shorthand for the Mexican Mafia.↩

- [27]Sam Quinones and H.G. Reza, “O.C. Mob Suspect Seen as a Pioneer: The Mexican Mafia defendant allegedly prompted prison group to move to the streets,” LA Times, June 20, 2005.↩

- [28]Brentin Mock, “Ethnic Cleansing in L.A.: Acting on orders from the Mexican Mafia, Latino gang members in Southern California are terrorizing and killing blacks,” from a Southern Poverty Law Center Intelligence Report, Alternet, January 19, 2007. Yes, the SPLC is alarmist, but facts are facts.↩

- [29]James Alan McPherson, “Chicago’s Blackstone Rangers, Part 1,” Atlantic, May 1969.↩

- [30]“Congress Investigates Civil Disorders, Gangs,” CQ Almanac, 1968.↩

- [31]“A leader of the Four Corner Rangers, whose members described themselves as a ‘brotherhood’ of the Blackstone Rangers, was credited by police with breaking up a potentially dangerous crowd that pressed toward Langley avenue from an easterly direction in 43d street last night,” from “South Side Crowd Stones Police as Protest Rally Sets Off Uproar,” Chicago Tribune, September 15, 1967.↩

- [32]CQ Almanac, 1968.↩

- [33]McPherson, Part 1, Atlantic, May 1969.↩

- [34]McPherson, “Chicago’s Blackstone Rangers, Part 2,” Atlantic, June 1969.↩

- [35]It’s not clear what happened, and while most people believe Fort had Cogwell killed, some think that Chicago mafia killed him to squash his union organizing.↩

- [36]Maurice Possley and Ray Gibson, “Noah Robinson Enigma Grows,” Chicago Tribune, June 12, 1988.↩

- [37]Matt O’Connor, “Noah Robinson Is Found Guilty Again in Retrial,” Chicago Tribune, September 27, 1996.↩

- [38]The Youtube video of this Savior’s Day address, “Power, At Last… Forever!” has been edited so that it begins with Farrakhan’s speech, and not the preliminary addresses by Algeria’s Ahmed Ben Bella, Ghana’s Jerry Rawlings, and Libya’s Qadaffi. However, if you fast-forward to around 4:08, you can see Qadaffi on a TV monitor. See Natalie Y. Moore and Lance Williams, The Almighty Black P Stone Nation (2011), p. 156.↩

- [39]Louis Farrakhan, “The Nation of Islam Welcomes Muammar Gadhafi,” Final Call, September 29, 2009.↩

- [40]Natalie Moore, “Muammar Qaddafi’s Chicago Connection,” The Root, March 16, 2011.↩

- [41]NPR interview with John Lippert, the author of the definitive investigative piece about Chicago and the Sinaloa cartel, on February 14, 2014.↩

- [42]Housing and Urban Development.↩

- [43]“Tenants receive relocation assistance and a portable Section 8 voucher to subsidize their rent in the private market while their public housing developments are demolished—entirely or in part—and reconstructed as mixed-income housing complexes in an attempt to deconcentrate pockets of intense poverty,” James Tracy, “Hope VI Mixed-Income Housing Projects Displace Poor People,” Race, Poverty, and the Environment, “Who Owns Our Cities?” Spring 2008.↩

- [44]Please, please, please see the rest of this article “The Change They Believe In” by the late Bob Fitch on Obama’s real-estate cronies. It was transcribed for Chairman Bob Avakian’s Revolutionary Communist Party newspaper, Revolution, from a speech Fitch delivered to the Harlem Tenant’s Association on November 14, 2008.↩

- [45]Andre F. Shashaty, “Valerie Jarrett’s Struggle: Chicago developer fights a familiar battle to realize her grandfather’s dream,” Affordable Housing Finance, November 1, 2008.↩

- [46]Fitch, “The Change They Believe In.”↩

- [47]John Lippert, Nacha Cattan, and Mario Parker, “Heroin Pushed on Chicago by Cartel Fueling Gang Murders,” Bloomberg Business, September 16, 2013. This is the definitive article on Chicago and the cartel.↩

- [48]William J. Bratton, “The Real Story of Chicago’s Bloody Summer: The city has seen nearly 300 killings this year, but over two decades its rate of violent crime has dropped 50 percent,” Wall Street Journal, July 20, 2012.↩

- [49]Lippert et al., “Heroin Pushed on Chicago by Cartel Fueling Gang Murders.”↩