On October 6, 1976, thousands of Thai police and rightist paramilitaries violently drowned a protest at Thamassat University in blood.

The protesters were fighting against the return of anti-communist Thanom Kittikachorn, the former military dictator of Thailand. Thanom was overthrown in a popular uprising sparked by inflation and food shortages in 1973. Radical demands followed and made the ruling classes uncomfortable. The overthrow of the kings in neighboring Cambodia and Laos in 1975 made them tremble. Thanom’s return and plan to stage a coup had the blessing of the king.

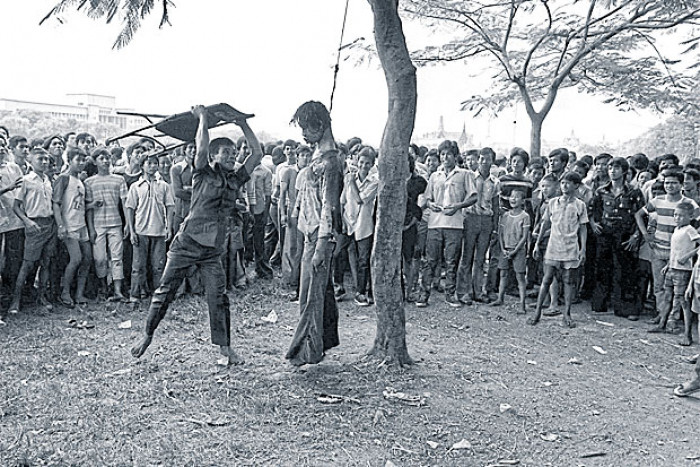

Word spread quickly and people mobilized. The reaction was just as fast. Two workers putting up anti-Thanom posters were lynched by police. Protests gathered at Thamassat in the center of Bangkok and unleashed a brutal attack. Over a hundred were killed and many more were injured. Public lynchings and beatings in the streets of Bangkok were famously captured by American photographer Neal Ulevich.

October 6, 1976, massacre. Neal Ulevich / Associated Press.

October 6, 1976, massacre. Neal Ulevich / Associated Press.

Some reactionary forces justified the massacre with a claim that protesters were insulting then crown prince Vajiralongkorn. Thailand has one of the harshest and most backward lese majeste laws in the world. People can even go to prison for 15 years for insulting the “royal dog.”

What followed the massacre was a return to open right-wing dictatorship with the sponsorship of the crown. A Maoist movement broke out and eventually launched a “people’s war.” Regional and class struggles continued. Some of this is fleshed out in the letters from Thailand published in Insurgent Notes during the last period of major protest in 2014.

Now protests have once again broken out in Thailand. These protests are not the same old street protests. They have shaken Thailand and indeed Asia. They are arguably the most serious events in Thailand in the last forty years.

A military coup in 2014 set the stage. It was the third time a member of the Thaksin family was overthrown by the military. The military finally announced new elections in 2019. A social democratic party was formed by the wealthy Thanathorn Juangroongruangkit. He followed in the footsteps of Thaksin Shinawatra, one of the richest people in Thailand, but did not follow Thaksin directly.

The 2019 election was a return to form. Thaksin’s party once again won the most seats. Through maneuvering, the general in charge of the military dictatorship was named prime minister. Thanathorn’s social democratic party won several seats but was soon disbanded by the courts.

In February, protests against the “legitimized” military government spread across universities. They started to peter out as a lockdown was announced in response to the covid-19 Pandemic.

The economic situation deteriorated. Tourism came to an abrupt halt and production slowed as well. Hardship became the norm for many people across Thailand. Meanwhile news of the exploits of King Vajiralongkorn started streaming in. The former crown prince now holds the top spot, making him one of the richest people in the world. As people across Thailand have learned, he spends much of his money in Germany where he lives in luxury with dozens of female consorts and servants. This made for fertile ground.

By August, student protests were openly criticizing the monarchy, something virtually unheard of in Thailand. In mid-September, 100,000 protesters amassed at Thamassat University, with many now openly criticizing the king.

The protests really picked up steam in October, on the forty-fourth anniversary of the Thamassat Massacre. First a small group of protesters gathered to “salute” the king’s motorcade. Only the “salute” was one with three fingers. This comes from the Hunger Games stories. In that story the poor flash three fingers at the rich urban-based rulers who are protected by the military. It’s easy to see the connection. Twenty-one protesters were arrested.

The next day, a mass protest was planned to march on the Government House. The government bused in right-wing royalists. Around two hundred thousand protesters showed up. The rightists attacked them but were unable to stop their march. At this point, the protesters started referring to themselves as the “People’s Party,” a name which harks back to the group that overthrew the absolute monarchy in the 1932 Siamese Revolution. They also set up an occupation.

On October 15, the government declared a “severe state of emergency.” They outlawed all groups of more than four people and threatened anyone who protested with arrest. Hours later, tens of thousands mobbed the downtown shopping district in numbers that simply overwhelmed the police. They occupied the position for hours.

On October 16, the government announced a month-long state of emergency with the possibility of marshal law. Defying the orders, thousands gathered in downtown Bangkok. This time the police were ready. Protesters were sprayed with chemicals shot through water cannons. Many protest leaders were arrested.

The government closed several train stations in another attempt to stem the tide. When that didn’t work, they closed entire train lines. The now leaderless protesters responded by calling for protests at every train station.

Protests keep growing. Flash mobs drummed up on a moments notice are now a regular occurrence. On October 17, 18, and 19, hundreds of thousands took to the streets. Huge crowds occupied intersections and the democracy monument in Bangkok shouting: “We are all leaders.” Other protests broke out across the country. There is no sign of slowing down.

The old fault lines can be seen, but there is also a lot that is new. The poor farmers and workers, largely hailing from the impoverished Isaan region, have traditionally been on the “red shirt” side. They are joined by restive elements from the north and workers from all over the country. The urban-based Sino-Thai bourgeoisie with its strong ties to the monarchy1 have traditionally been on the “yellow shirt” side. They are joined by the substantial number of people tied to the military, police, crown or state bureaucracy in one way or another. Nothing has changed there.

What has changed is a melding of student and republican protesters with mass protests for economic relief and other reforms. When commentators call these protests unprecedented, they are not kidding. While not officially organized behind any particular party, protesters are united in calling for the resignation of the government and the creation of a new constitution written by popular consultation.

Age-old prohibitions against even discussing the crown have dissolved seemingly overnight. While there is still a strong royalist element, the balance of forces has shifted in a major way. At least for now!

People have taken notice of these protests in nearby countries. People in Hong Kong have especially taken notice. Messages of solidarity have been sent in both directions, and there is quite a bit of communication across the Internet.

This is a struggle that we should pay attention to. In this day and age, it is quite simple to reach out to some of the thousands of people involved in this. Efforts should be made to communicate with them, in the Thai language wherever possible. These sorts of schisms don’t come along every day.

There is also a real danger for the protesters. Right-wing forces like the so-called Trash Collectors are mustering and biding their time. They march under the same banner as their predecessors. And if they justified public lynchings with a claim that Crown Prince Vajiralongkorn was insulted, just imagine what they will do now that King Vajiralongkorn is being openly criticized.

- See “The Crown and the Capitalists: The Ethnic Chinese and the Founding of the Thai Nation,” by Wasana Wongsurawat.↩︎