The events of May 1968 in Paris and around the world reverberated in Britain, in its industrial relations, in the wider culture and on the left.

Rodney Kay-Kreizman was arrested on the Vietnam demonstration at Grosvenor Square, March 17, 1968, “a pitched battle with the police”:

I went to help a young woman, who was being set upon by three policemen, and rugby-tackled one of them. She got away, but I was arrested. The next morning, I was up before the beak, who gave me three months suspended.

Rodney had joined a group of socialists in Nottingham—“in 1956 [after the invasion of Hungary] everyone was moving out of the Communist Party just as I was moving towards it.” “Ken Coates, a sociology lecturer at the University, an ex-miner, Pat Jordan and John Daniels, an education lecturer.”

“Along with Tony Topham, who was a lecturer in Hull, they set up the Institute for Workers Control,” says Rodney:

We were nominally in the Labour Party, but it was really a group of its own, linked to the Fourth International. We had a magazine, The Week, which offered “News Analysis for Socialists.”

The Week was the focal point of a group that had supporters in “the East Midlands, in Sheffield, Nottingham, Derby and Rotherham.” Some of Rodney’s connections were friends first, and “we met on demos on Market Square” in Nottingham. “As an ex-serviceman I was against Suez.”

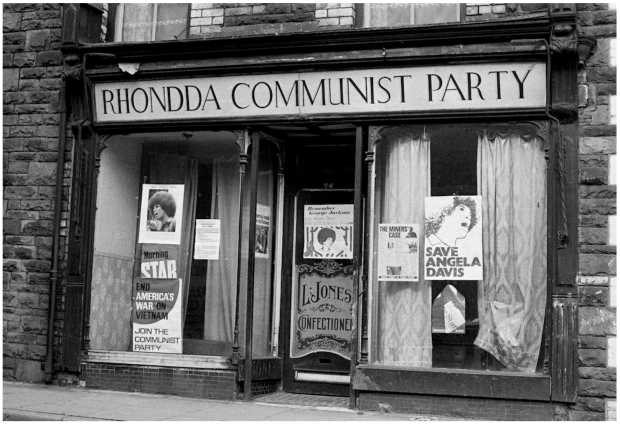

The Communist Party was “on the wrong side of everything. They wanted peace in Vietnam and we wanted a victory to the Viet Cong. They would have had two Vietnams, and two Koreas.”

After the Second World War, the Communist Party of Great Britain’s police was “all about peace”: They had Peace rallies and Peace Conferences—and they wanted peace in the workplace as well. They were always for a “fair settlement”—but we wanted workers’ rights, and workers’ control. We favoured an independent shop steward’s movement. We took up issues like health and safety because we wanted them under the control of the workers.

“That was our vision: workers’ control. Their vision”—the Communist Party’s—“was Government control of big industry, big nationalised monopolies, like in the Soviet Union.”

“There was a lot going on in 1968—it was a time of hope and optimism and people doing things for themselves. I haven’t changed my views, but I think I am out of my time now. We’ve had the Labour Party shit on us all the time. The whole society has moved to the right. Trade unions are at their lowest ebb ever.”

“The reason Corbyn is being attacked so viciously now is because they are afraid of the optimism of the 1960s—because they have no answers, they have no answers to the problems of robots taking jobs, and to mass poverty.”

Susan Caffrey was protesting in Red Lion Square, too. She was a student at the North West Poly in London. “We were all going.” Back then “there was the idea that we would take the streets—like they had in Paris. It was very exciting.” There were meetings about the Vietnam war going on at colleges all over London, and Susan can remember hearing Robin Blackburn (later editor of the New Left Review) and Tariq Ali speaking at the London School of Economics (lse). Later, on the radio, “Tariq Ali said that they would paint the leaves red in Grosvenor Square, but it was too early, and the leaves had not come out.”

In 1968 Patrick Hughes was “teaching at Leeds College of Art which had already been revolutionised,” pioneering the experimental approach others copied. “The revolution in art schools happened because of Harry Thubron.” Under him the college decided “to get with it. To bring performance art, painting, sculpture all together.” Thubron asked “why have we got a painting and a sculpture department?” They should be together—“like Kurt Schwitters.” At Leeds they “wanted to be ‘modern’ but not just in a formalistic way.”

The two dogmas in art were “social realism,” which was “realism with all four feet on the ground” in Eugene Ionescu’s words. The other “monolithic vision of art was abstract expressionism,” that “art was like music, all about tones and affect.” The radicals at Leeds “just wanted more variety than social realism and abstraction.” They wanted “imagination and creativity…and humour, as Tony Earnshaw [a lecturer and artist at nearby Bradford College] would say.”

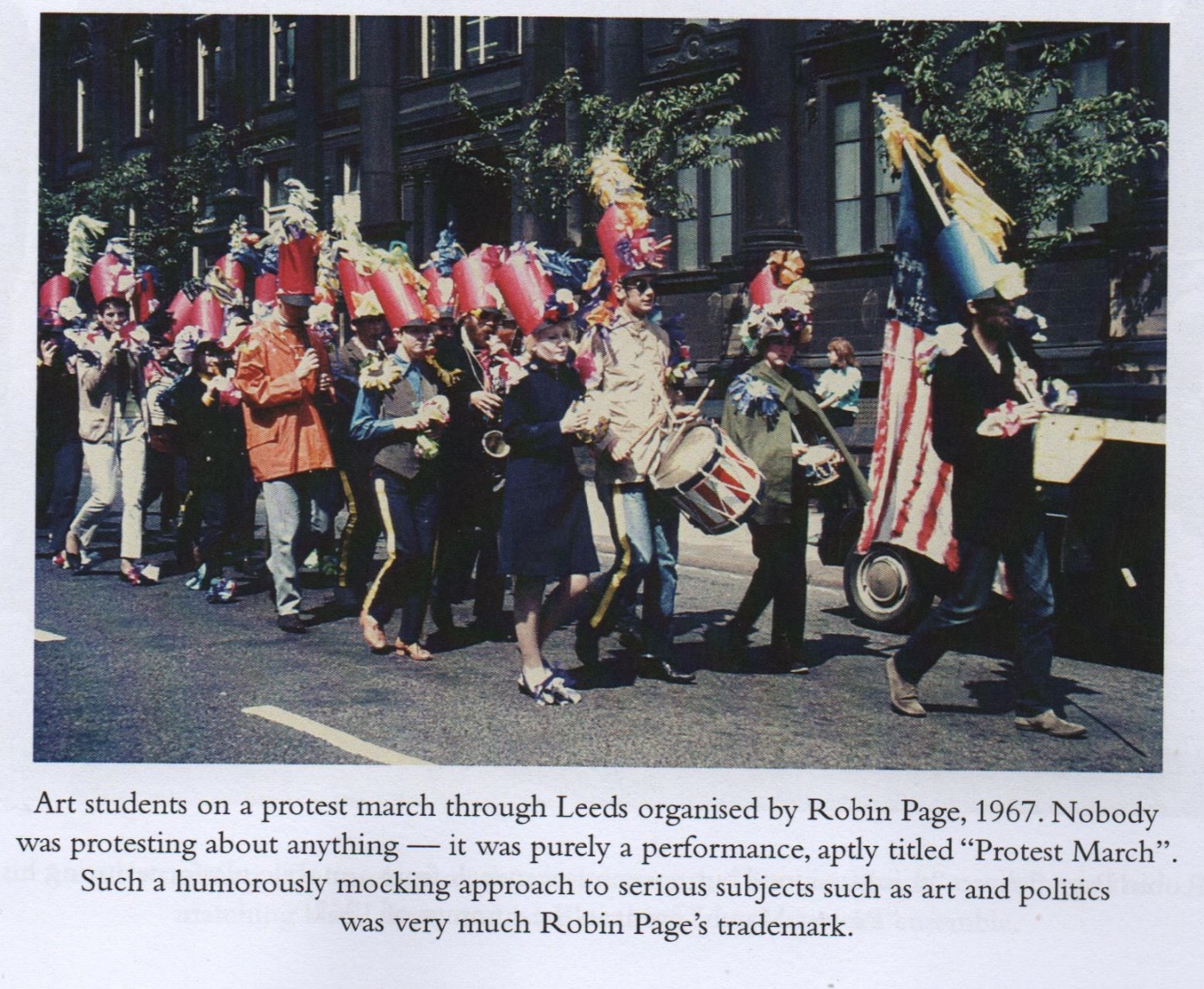

Among those in the Leeds Art School were Robin Page and George Brecht who were with the “Fluxus” group; their works were called performances or happenings. Yoko Ono, who would marry John Lennon, was allied to Fluxus, too. In one performance Robin Page kicked his guitar down the street and the audience followed after him. In another, in 1967, called “Protest March,” 200 students demonstrated, with no collective demand, but each with his own banner or cause—and I was on it too. My mother’s placard read “Kick Against the Pricks!” and mine said “Hands off King Kong.”

Harry Thubron went on to teach at Goldsmiths where his approach nurtured artists like Damien Hirst and Sarah Lucas. Leeds College of Art inspired the revolutionaries at Hornsey, who occupied their college.

Hughes is sceptical about the “zeitgeist” of 1968. “I don’t believe in spirits.” Most of the country was still living in the 1940s. Shortly after the riots in Paris, Hughes visited his friend there, George Brecht. The students had ripped up the small pavé (paving stones) to use as missiles against the police. When he got to the door of Brecht’s Paris apartment, it was open but walking in he was surprised to see Brecht throw a pavé straight at him. Instinctively he grabbed it. “It squeaked.” “It was made of rubber, with a little whistle valve so that it squeaked when you squeezed it, like a child’s doll.” “I was impressed at how quickly the practical jokers had détourned the May events.” Inventiveness and creativity “were always there, under the surface, waiting to break through.” You could see the same playful use of language and imagery in the work of Tristram Shandy in the eighteenth century, or in Lilliput (the 1940s magazine) or the Beano (children’s comic), he said.

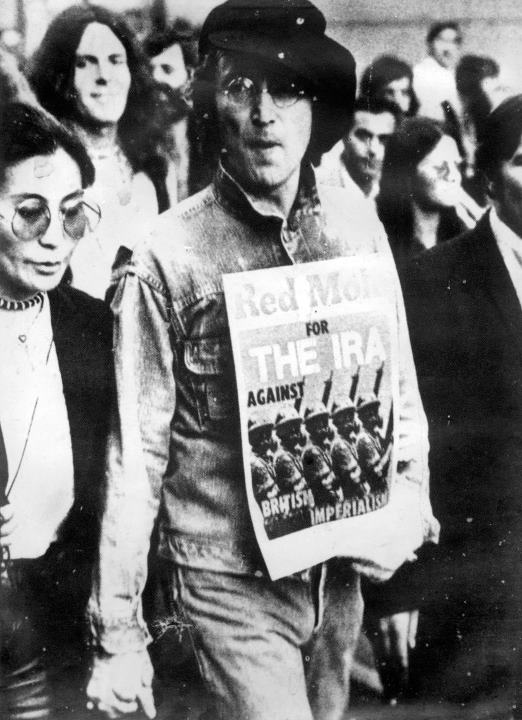

Mick Owens was fourteen in 1968 and living on a council estate in Birkenhead. His older brother was in a band—the Globetrotters—a part of the Merseybeat sound. “He worked night at Cammell Laird [shipbuilders]—well mostly sleeping off excitements of that evening.” Van Morrison’s “Astral Weeks came out that year, which we listened to, but probably more the Small Faces.” “We were into Motown and thought of ourselves as “mods.” “In 1968 we listened to the Beatles White Album, and the track ‘Revolution Number Nine’ was all experimental, by [the Fluxus artist] Yoko Ono and John Lennon, with different recorded tape loops played over one another.” “Like an action painting,” said Lennon in an interview. Even on a council estate in Birkenhead you were a part of what was going on, Owens explains. On the other hand, “the idea that 1968 was a thing never occurred to us.”

Social historian Lucy Robinson explains that for the Labour governments of the 1960s there was a “move away from class and production towards issues of identity and fairness,” that were evident in the liberalisation of laws on divorce and the semi-legalisation of homosexuality.1 The growing importance of the politics of consumption, with a greater emphasis on youth and pop culture chimed with the post-war boom, and with a New Left.

Meanwhile, in Derry, in British-occupied Northern Ireland, events were more on the cusp of all-out conflict. Tommy McKearney remembers “a civil rights march approached the Craigavon Bridge and was halted by an ruc cordon”:

Initially, taking the advice of veteran trade union leader and Communist Party activist Betty Sinclair, the marchers sat down in the street and started to sing. After a few minutes, a young student activist stood up and began counting the police. She estimated that the sedentary marchers had numerical superiority and could overwhelm the police ranks and push their way into the city if the crowd charged forward.

As McKearney says,

After a few minutes, they burst through the ruc ranks and poured into the city. Leadership of the radical street protest in Northern Ireland had passed from the generation guided by Betty Sinclair to a new generation of activists inspired by Bernadette Devlin, the young woman who had called the advance.2

The following year Bernadette Devlin was elected to the House of Commons, at the age of 21 as the “Unity” candidate of Irish Republicans and Socialists. Soon after, Bernadette Devlin spoke at the North West Poly in London and Susan Caffrey remembers being blown away: “she was nothing like the MPs of the time.”

The events of May 1968 centred on Paris, but they resonated strongly in Britain, too. In his memoirs Alan Thornett remembers the chair of the Joint Shop Stewards Committee at the Cowley car plant opening the meeting by proclaiming “a spectre is haunting Europe.”3

The real force behind these sentiments was the slow disintegration of the post-war, corporatist settlement between organised labour, industry and the government—the so-called “tripartite system.” In wartime industry and labour had been drawn into collaboration, elements of which survived after the war. Full-time union officials, local convenors and general secretaries were all involved in cooperating with management. This was the “fair deal” that the Communist Party was promoting. But over time these practices and institutions were inadequate to both the ambitions of the workers on the one hand, and the employers’ “modernisation” plans on the other. Younger shop stewards who had not been socialised into the arrangement were much more confident about taking “unofficial” strike action.

The “New Left” was well placed to take advantage of the collapse of the old tripartite order—it was created out of the protests at the Stalinist compromises. The group around The Week joined up with Tariq Ali to become the International Marxist Group, and in Ireland, the student campaign People’s Democracy were talking to them, too. Some of those student leaders at the lse joined up with the New Left Review that Perry Anderson and ep Thompson had helped to create.

The New Left Review’s “Partisan Café”

The other left-wing group that rode the wave of Labour Party and trade union activism were the International Socialists. Their leaders traveled light intellectually, leaving a lot of Marxist theoretical baggage behind: Lenin’s theory of imperialism was out of date, they said, and the arms economy could offset the long-anticipated economic collapse indefinitely. Such iconoclasm helped them to attract talented young students like Paul Foot, the Hitchens brothers, Peter and Christopher, Irene Bruegel (who did fine work analysing labour markets and women’s position in them) and the philosopher Alasdair McIntyre.

For the next decade it looked as if the revolutionaries might overthrow the system.

Days lost to strike action rose to 24 million in 1972. According to the government white paper, “In Place of Strife,” “95 per cent of all strikes in Britain were unofficial and were responsible for three quarters of working days lost through strikes.”4 The conflict in Northern Ireland went straight into fourth gear when the Unionist authorities lost control and called in the British Army. Some senior establishment figures talked about the need for a military takeover.

The powers-that-be were thrashing around, without any sure idea of how to keep order. Militant workers kept on striking. But crucially the revolutionary forces lacked the will to step in and take control. The International Socialists’ leader Tony Cliff summarised in 1975 that:

We are entering a long period of instability. International capitalism will be rent by economic, social and political crises. Big class battles are ahead of us. Their outcome will decide the future of humanity for a long time to come.5

Cliff’s plan of waiting for objective forces to drive people to revolt was a recipe for defeat. This was the essential flaw of the International Socialists—their fear of “substituting” themselves for the class made them reluctant to fight for political leadership. Instead, they left politics to the Labour Party.

The New Left Review had done well relating to the new mood, even setting up New Left Clubs. But it shied away from the goal of overthrowing the state, preferring instead a reform of what it assessed to be an “incomplete bourgeois revolution” (this was known as the Nairn-Anderson thesis, after its authors Tom Nairn and Perry Anderson). Revolution in faraway places featured in its articles, but it was more cautious about social change in Britain.

Leo O’Neill, who had been in People’s Democracy in Newry, Northern Ireland, told me that the whole organisation there was debating the drafts of Michael Farrell’s analysis of the situation there. But when it was finally published as The Orange State, good as it was, it was clearly not the key to the Irish revolution (I guess that what they really needed was a critique of the shortcomings of Irish Republicanism, as a guide, rather than a critique of the Orange State, which most people they were talking to had a good idea of anyway). The only real challenge to British rule was coming from the Irish Republican Army, whose limitations were hidden by the intensity of the conflict.

The Communist Party in Britain recovered after the shock of 1968, and it even grew on the back of the workplace militancy of the 1970s. The two wings of the party were those organised around the older union convenors, and the others, who called themselves “Gramscians” and indeed saw themselves somehow as heirs to the évènements in Paris.

Far from collapsing, the Communist Party learned to relate to the new mood. Meanwhile the ruling classes recovered their composure and fought for their preferred outcome to the collapse of the post-war compromise. Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative Party had its answer to the shortcomings of corporatism, and their inner confidence won them the election in 1979—appealing first and foremost to middle-class fears of social disorder. The Thatcher government’s root and branch reforms had a formal similarity to those the New Left was arguing for. Both were seeking to overthrow the post-war corporatist order, but her government was doing it from the right. As Tom Nairn and Perry Anderson were railing against Britain’s “gentlemanly capitalism,” Margaret Thatcher was taking on the “Grandees of the Conservative Party” and the “Union Barons.”

The Conservative governments “resolved” the problems of British capitalism by forcing through a thoroughgoing reform of industry, not by modernising production, but by breaking up working-class institutions, and social solidarity. It was her Conservative revolution that ended up shattering the post-war compromise, and fatally wounding those who championed it: the old Labour Party and the Communist Party. The International Socialists got to be a lot more dogmatic, for reasons of internal coherence, losing much of the élan of their earlier years.

The New Left had suggested an alternative resolution to the barriers faced by British society in 1968, one that emphasized creativity and freedom, and even workers’ control. In that they made a great contribution to the decades that followed. But practically speaking they failed to realise that alternative. They were much better at diagnosing the problems of the day than they were at crafting solutions. When the governing classes were at a loss for what to do, the revolutionaries of ’68 were—surprisingly—too cautious, or perhaps too virtuous, to step into the breach.

Many have made the point that the rebels of ’68 provoked a greater reaction against them than they gathered support. In Britain, even though the voting age was lowered to 18 in 1969, the Conservative Party (under Edward Heath) won the election in 1970. All the same, the influence of the activists of 1968 was profound. British political leaders like Gordon Brown, Charles Clarke, and Tony Blair were all students of the New Left. So, too, were Jeremy Corbyn and John McDonnell. Entrepreneurs like Richard Branson and David Puttnam were products of ’68, too. Looked at another way, the influence of the ’68 generation was generally more effective in the criticism of the old arrangements than it was in the formulation of the new. When the French ’68ers became “postmodernists” and “deconstructionists” they were making a virtue of that political approach. English academics were frightened of those difficult theories, but they did over time learn from the French the dubious lesson that “the age of grand narratives” was over.

Looking at the state of the nation fifty years on, the obvious signs of reorganisation come from the 1980s. It was then that collective bargaining made way for individualised labour contracts; and it was then that many nationalised industries and public services were privatised. But look further, and you can see the influence of ’68 in the growth of identity politics and the shift towards a consumer culture. But most of all, the legacy is that critique is a stronger force than construction; since 1968, the driving force of social organisation has been the dismantling of the old institutions, without creating new ones.

James Heartfield lives in London.