Gentrification is a form of producing space that currently attracts a great deal of attention in South Korea. Referring to “a process involving a change in the population of land-users such that the new users are of a higher socio-economic status than the previous users, together with an associated change in the built environment through a reinvestment in fixed capital,”1 gentrification has until recently remained in South Korea a critical term which circulated only narrowly in professional academic fields; now, it has become a commonplace even among ordinary people. Since the mid-2000s, the term has widely been used to refer to urban renewals and beautifications changing the looks and composition of the built environment in the neighborhoods. Strictly speaking, however, what Korean people these days call gentrification should be considered “commercial gentrification,” which is to be distinguished from “new-build gentrification.” The former form has recently become more common and widespread as a capitalist spatial practice, while the latter form appears to have lost much of its vitality.

As far as South Korea is concerned, it was the new-build gentrification that played a dominant role for a long time in the capitalist production of space. This has to do with the fact that the country took a developmentalist approach to its economic growth. As it never provided a robust welfare system to support the population, the Korean state instead constructed a surrogate system in the form of the real estate industry. As the French urban geographer Valérie Gelézeau recently pointed out, South Korea has as a result developed into a “republic of apartments.” In the capital city Seoul, for instance, as of 2010, “apartments”—housing units belonging to buildings higher than 6 stories—and “villas”—housing units cheaper and smaller than apartments and belonging to buildings lower than 5 stories—constitute 60 percent of the total housing stock. The portion of the “private houses” which used to be typical housing units until the 1980s has now dwindled to about 30 percent of the housing stock.

As can be guessed, for most Koreans the ownership of decent apartments has become the major, if not only, dream. For becoming an apartment owner was the same as being promoted to the middle class in the country. And understandably it was Korea’s developmental state that played a crucial role in creating this republic of apartments. Beginning in the early 1970s, the Korean government initiated massive construction projects, building mega apartment complexes in big cities. Of course, Seoul was the first city to develop such complexes. And as a recent global hit “Gangnam Style” suggests, it was the Gangnam area that first saw the urbanization of the capital city. This was the beginning of new-build gentrification in South Korea. And you can see the outcome today in the cityscape of big cities, the capital city Seoul in particular, where “the gray skyline along row after row of near identical concrete apartments” is unfolded across the whole city.

While it was instrumental in determining the looks and composition of Korean cities, new-build gentrification appears to have seen its heyday, however, for, since the global recession of the late 2000s and early 2010s, the number of the development projects underway in the new-build form sharply decreased. Many of the projects planned before the crisis, including that of the International Business Area in the Yongsan District that was to cost $28 billion, and that of the Mega Metropolis Eight City that was to cost a whopping $288 billion, were canceled. In addition, it appears that at least within the vicinity of the capital city, land large enough to permit massive construction projects is no longer available. While there are some projects still going on in the form of new builds, their scale no longer matches that of the earlier projects. While this does not mean that gentrification has receded as a dominant spatial practice in South Korea, its prevailing form seems to have undergone a fundamental transformation from new-build to commercial gentrification.

There are several aspects by which commercial gentrification is distinguished from new-build gentrification. Most noticeable among them is that the construction size of the former is much smaller. New-builds used to be as large as mega apartment complexes, towns, or even cities. Commercial gentrification, in contrast, takes place generally in individual buildings or in street blocks at its largest size. In addition, it tends to keep at least some part of the former buildings—the walls, timber, windows, or color. This practice is radically different from that of new-builds that tends to demolish the entire existing built environment in the area where gentrification takes place. And of course, the new form provides commercial spaces as its products, whereas residential units are the main products of new-builds. It is crucial to note that gentrifiers are different in both forms of gentrification. The features that distinguish commercial from new-build gentrification derive from the fact that the former proceeds with individuals participating in the transformation of the built environment. While new-build gentrifiers are often the “development collectives or alliances” consisting of local influentials, governments, politicians, financiers, banks, lawyers, pro-development academics and the press, commercial gentrifiers tend to be individuals who have accumulated funds—whether borrowed or saved—to invest in the redevelopment of small-scale buildings. One reason why the term “gentrification” should today in South Korea be regarded as commercial gentrification is that since the late 2000s, neighborhood redevelopment in the form of commercial gentrification came to the fore, whereas the new-build form has receded.

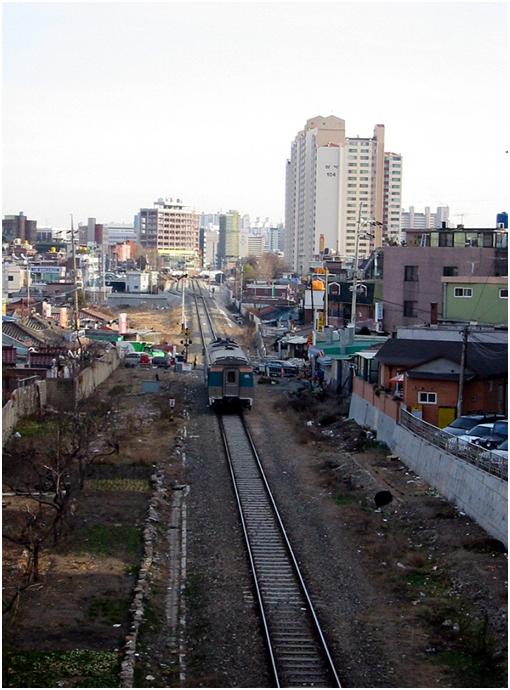

The old Gyeongui Line before it was put underground.

The old Gyeongui Line before it was put underground.

A core part of my argument is that this transformation has to do with the recent changes in financialization in South Korea. Commercial gentrification started to show itself not coincidentally in the late 2000s when the world economy was seriously hit by an unprecedented financial crisis. The most important reason that pre-planned new-build projects had to be scrubbed must be found in this crisis. Projects after projects, including the two megaprojects mentioned above, were thrown away in its aftermath. While it was caused by the global failures of financialization and those of the neoliberalism that had turned financializing the economy and other social practices into a new strategy of capital accumulation, it is important to remember that the financial crash in the late 2000s did not bring financialization to an end. In the United States, where the crisis first occurred, in Europe where the “sovereign crisis” took place, and in the emerging economies, where another crisis loomed, economic policy makers without exception kept financialization intact. The strategy taken to overcome the problems of the financialized economy was to further financialize it. One prominent example is the “quantitative easing” programs most crisis-hit countries adopted to keep interest rates at their historical lows. This measure had the added effect of even forcing people to borrow as much money as possible, turning them into investors-cum-borrowers rather than savers. I think that the emergence of commercial gentrification in Seoul as a new form of gentrification had to do with this situation.

While South Korea’s economy became financialized with the introduction of neoliberalism in the early 1980s, its full-scale financialization took place when the country had to borrow a bailout fund from the imf in 1997 in overcoming the foreign currency crisis that shook the entire nation. Before 1997, South Korea did not have a full-fledged financial or capital market other than banking and stock markets, the state tightly controlling money flow within and across the borders. After the foreign currency crisis and the imf’s intervention in its economy, however, the country adopted fundamental policy changes to financialize its economy. It took only a couple years to introduce the necessary financial instruments, including financial derivatives—such as forwards, futures, options, swaps—project finance, asset-backed securities (abs), mortgage-backed securities (mbs), asset-backed commercial paper (abcp), mutual funds, public offering funds, private equity funds, real estate investment trusts (reits), and so on. As the result of this introduction of financial mechanisms, South Korea came to possess a fully financialized economy.

Now, I have to point out that the financialization of the economy encouraged and was intensified by that of space in the country. It was in the late 1990s and early 2000s when a wholly new capital market was formed that the financialization of space in Seoul began in earnest. And this change also affected the way gentrification took place. As mentioned, gentrification had been the most powerful way of producing space in Seoul since the 1970s when capitalist urbanization began in earnest. But before financialization measures were put in effect in the late 1990s, gentrification had little to do with the financial market. Most gentrification projects were largely state-driven, and apartments, their main products, were offered to consumers who depended more or less on their savings to buy homes. As apartments or other forms of housing were the most important property for people, this must be one reason that the savings rate of South Korea was exceptionally high until the 1990s.

The financialization of the economy after the imf bailout fundamentally changed the situation. Gentrification increasingly became financial market-driven. As a result, there began to appear a noticeable change in the way people regarded their properties, especially real estate. While they used to be the most sought-after commodity—for they also served as arguably the major means by which to accumulate personal wealth—apartments tended to be savings or consumption funds until the late 1990s. After the financialization of the economy, they now became more like assets to be exchanged in capital markets. What intensified this trend was the neoliberal policy to turn people into new subjectivities. They were now encouraged to behave not merely as consumers who saved their money but rather as investors in possession of funds. It did not matter whether the money was saved or borrowed. This trend was supported by the government’s changed policy after the (neoliberal) financialization of the economy. Beginning in the late 1990s, financialization measures began to ease money flow or increase financial mobility, mainly through the lowering of interest rates to a historical low. The boom in new-build gentrification in the late 1990s and early 2000s, as shown in the unusual rise of megaprojects, must have to do with the fact that people tended to borrow money to invest in real estate. This can be shown statistically. Since the beginning of the twenty-first century, the total balance of mortgage loans has increased from 131 trillion won (18 percent of the gdp) in 2002 to 533 trillion won (32.5 percent of the gdp) in 2016. In parallel, the national household debt increased more than six times from 211 trillion won in 1997 to 1344 trillion won in 2016, while the gdp increased three times from 506 to 1637 trillion won in the same period.

In the process, the real estate sector increased its share in the economy even further. The balance of real estate project finance, for instance, reached 100 trillion won, about 8 percent of the gdp in 2010. In 2013, the amount of construction investment was 14.9 percent of the gdp, fourth highest among oecd countries. One result of this can be seen in the new cityscapes currently dominating the visual environment of Seoul. Before the late 1990s, there was only one skyscraper higher than 50 stories. Now the capital city has 21 such super–high rises, and South Korea comes fourth after China, the United States, and the Arab Emirates, in terms of the number of buildings higher than 40 stories.

An alley in Seochon before gentrification. Open source (?).

An alley in Seochon before gentrification. Open source (?).

For the last 10 years, however, South Korea’s capitalist production of space has adopted a new form of gentrification. New-build gentrification still continues, but it has lost much of its vitality. This had to do with the fact that in the late 2000s neoliberalism as a contemporary capitalist regime of domination faced a serious blow from what is considered the greatest financial crisis since the 1929 stock market crash. As already mentioned, neoliberal forces did not abandon financialization as a strategy of accumulation; it clung to financialization as can be shown in the application of the quantitative easing approach in most important capitalist countries to keep their economy running. In the production of space as well, financialization was kept as the main instrument for new construction projects, but in a different form.

Like other capitalist countries, South Korea and its real estate industry could not avoid the effect of the global economic crisis, as shown in the cancellation of such megaprojects as the Eight City. As a result, there followed the retreat of state institutions, big capital, and construction conglomerates from the gentrification market. In the meantime, there emerged a new form of gentrification as an opportunity for certain individuals to increase their wealth. According to a newspaper report, a Mr. Kim invested 13.1 billion won (us $13,000,000) over the six years between 2010 and 2016 to buy six store buildings in the vicinity of Hong-ik University, an area that recently turned into a hot place. What was surprising was that he borrowed most of the funds from banks by putting up 11.2 billion won ($11,000,000) as collateral, which means that he became the owner of the six buildings using just 2 billion won ($2,000,000) as seed money.

A gentrified Seochon alley. Photograph by Shin Sang-soon.

A gentrified Seochon alley. Photograph by Shin Sang-soon.

An ardent borrower like Mr. Kim is not rare in today’s Korea, for his kind of practice is being promoted by the official policy decision to lower interest rates to encourage people to borrow money to engage in real estate dealings. Low interest rates, which came further down after the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, no doubt, contributed to turning individuals into asset holders and investors with borrowed money, thus boosting commercial gentrification. As a result, however, cases of modern day enclosure increased, displacing more and more people from the base of their livelihood.

One major reason why the term “gentrification” has recently become a commonplace in South Korea is that several incidents of enclosure associated with commercial gentrification attracted public attention. Here I cite just one example. Takeout Drawing was a café that operated as a space for artist-led cultural projects like exhibitions, performances, educational and residency programs. In 2014, its operators faced displacement from the building where they ran the café, when the new owner, world-famous singer psy, wanted to demolish it to construct a higher and more lucrative building in the same venue. They resisted psy’s attempt to displace them, and appealed to the court, with fellow artists, independent musicians, cultural practitioners, civil social activists, and human rights lawyers coming to help them in solidarity. But they lost the case, since the South Korean court considered the private ownership of property a supreme right.

The Takeout Drawing case illustrates how small shopkeepers and tenants in Seoul are affected by gentrification. Gentrification functions to raise the value of land and buildings. When Takeout Drawing opened in 2010, the price of the café venue was about 3 billion won (us $3,000,000), but within six months, it shot up to 6.3 billion won ($6,300,000), and when psy bought it in 2012, the price was 7.8 billion won ($7,800,000). Currently, it’s worth more than 10 billion won ($10,000,000). This rapid rise in the real estate price had to do with the gentrification rampant in the area. When buying his building, psy must have expected that if gentrified, its value would rise even higher. In expecting to increase his capital, psy was a typical financial asset holder in today’s Seoul. But in the meantime, the café operators lost a valuable venue for their business and cultural activity.

In the remaining section of this article, I would like to focus on some cultural, political, and economic implications of gentrification. Gentrification, including its commercial form, is a complex social practice. As such, it comprises not only political economy, but also cultural politics and cultural economy. Or it can be conceived of either as cultural political economy, economic cultural politics, or political cultural economy. This is not a play of words, but an attempt on my part to suggest the complexity of the way the economy, politics, and culture are intertwined together in today’s Seoul. This conception of gentrification as a complex whole consisting of different dimensions of social practice enables us to understand the displacement of Takeout Drawing operators as more than simply an economic, a political, or a cultural phenomenon. The cultural political economic perspective taken here helps us to understand the commercial gentrification in Seoul as a complex spatial practice, with implications related to society as a whole. In the following, I will mention just a few aspects of it.

Let us first take a very brief look at how cultural political economy operates in relation to the commercial gentrification going on in Seoul. We have already seen that South Korea’s political economy favors asset holders’ rights to private ownership over poor people’s rights to livelihood and housing. This political economy operates on the basis of cultural infrastructures. The neighborhoods where commercial gentrification has been active are those that have already turned into hot places like Itaewon or the Hong-ik University vicinity. These places have been made attractive to visitors, due to their location, cultural atmosphere, historical legacy, urban charm, and so on. These resources are basically cultural in nature, as they have non-economic values, and as such, tend to function as what David Harvey called social infrastructures. They may not produce surplus value by themselves, but they can improve the conditions for producing it. One can argue that commercial gentrification makes the best use of cultural resources as such infrastructures.

Commercial gentrification is involved in economic cultural politics as well. If we see culture as having to do with meaning, politics with power, “cultural politics” then refers to a social dimension where crucial power struggles take place over the production of meaning. Commercial gentrification occurs often with the claim to regenerate and beautify lagging-behind neighborhoods, suggesting that it increases their cultural resources and values. Of course, there are opposing interpretations of the same process, as shown by the attempt of Takeout Drawing operators and their friends to resist gentrification. But more often, it is the economic logic that prevails and has a final say in deciding upon whether or not gentrification will proceed. We can thus see how in the actual processes of gentrification cultural politics cannot avoid getting involved in the economy.

To round up the complex relationship between the economy, politics, and culture involved in commercial gentrification, we finally turn to how political cultural economy operates in commercial gentrification. By “cultural economy,” I refer to a double process in which the economy is culturalized, while culture is economicized. Commercial gentrification concentrates in hot places because cultural social infrastructures like galleries, concert halls, street scenes and spectacles, historic sites, and the like are rather intensively available there, offering gentrifiers with chances to make economic profits. In this case, what happens is the economicization of culture. But it is also the culturalization of the economy, for commodities in the gentrified areas tend to be valued for their cultural merits. In Yeonnam-dong, a recently gentrified area near Hong-ik University, one can see that what is being consumed is not only ordinary commodity items like clothes, food or drinks, but also a sense of place, status, belonging, urbanity, or culture. On a typical weekend night, restaurants and clubs in the neighborhood are crowded with customers, but this also means that poorer tenants and shopkeepers cannot stay there, due to the rise of rents. One should also take note of the political effect of gentrification’s cultural economy. I would argue that the over-all political effect of commercial gentrification in Seoul is conservative, since it basically favors the reproduction of capitalist social relations.

Whether new-build or commercial, gentrification is a complex whole as social practice. It certainly has an economic function, since it helps to accumulate capital. As an asset holder, psy must have wanted to make more money by expelling the café operators. Their displacement, however, was made possible also by the current political economic situation in South Korea where interests of private capital prevail over social solidarity and association. Commercial gentrification may prosper as long as the current form of political economy in which commodities are aestheticized to raise their money value. Along with these normal procedures of gentrification, however, cases of modern-day enclosure increase. In order to prevent people from being displaced from their base of livelihood, the current form of gentrification’s cultural political economy, economic cultural politics, and political cultural economy must come to an end. This means that we need to create wholly new ways of producing space and new forms of leading our lives.

-

Eric Clark, “The order and simplicity of gentrification: A political challenge,” chapter 16, The Gentrification Reader (Routledge, 2005), p. 258.↩

Okbaraji Alley (Prisoner support alley). Family members used to stay in the small inns of the neighborhood to provide clothes and food to the prisoners in the close-by Seodaemun Prison.) Photograph by the Task Force for Preservation of the Okbaraji Alley.

Okbaraji Alley (Prisoner support alley). Family members used to stay in the small inns of the neighborhood to provide clothes and food to the prisoners in the close-by Seodaemun Prison.) Photograph by the Task Force for Preservation of the Okbaraji Alley. The alley neighborhood (demolished in 2016) is now being replaced by an apartment complex. Photograph by Kang, Nae-hui.

The alley neighborhood (demolished in 2016) is now being replaced by an apartment complex. Photograph by Kang, Nae-hui. The Yeonnam-dong area along the Gyeongui Line Park recently underwent commercial gentrification. The former railroad has now turned into a 6.3-km-long inner-city park. Photograph by Kang, Nae-hui.

The Yeonnam-dong area along the Gyeongui Line Park recently underwent commercial gentrification. The former railroad has now turned into a 6.3-km-long inner-city park. Photograph by Kang, Nae-hui.