The weeks following the Ferguson non-indictment of Darren Wilson have resulted in a wave of protests all over the country, alongside the new array of new tactics, slogans, and nominal “movements” that tend to accompany major political events. However, as with many cities in the United States, the mobilizations in New York City between November and December surpassed what many had thought possible. Activists, politicians, police alike have been scrambling to make sense of the constellation of events that have followed the highly publicized police killings (and grand jury decisions) of Michael Brown, Eric Garner, as well as countless less-publicized murders. Moving from specific events toward a larger understanding of the recent national wave of struggles, several questions remain: are the recent mobilizations in NYC part of the movement signified by #blacklivesmatter and its vague tactical imperative (#shutitdown)? In other words, what is behind the general dynamic, whose local manifestations include a succession of spontaneous actions of thousands in direct response to the non-indictment of officers Darren Wilson and Daniel Pantaleo? And most important: what are the larger anti-systemic possibilities (and limitations) of these apparently new political orientations? Our account can only pose such questions in our brief (and inevitably partial) account. However, we believe provisional answers emerge from a close analysis of the shape and patterns of the post-Ferguson cycle of struggles that has unfolded across American cities since late November.

***

While brutal, high-profile police murders of unarmed black men in New York City are far from uncommon,[1] the actions on the night of the verdict were more spontaneous, massive, and aggressive than most NY protests in recent memory. Although protest chants are often little more than rhetoric (“whose streets?”), the strategy of this movement is eloquently summed up in one of its primary slogans: #shutitdown. In practice, shutting it down has meant employing a wide arsenal of tactics to bring to a halt the normal functioning of the city. Most often this taken the form of large and simultaneous marches blocking major traffic arteries or transportation hubs: bridges, tunnels, highways, freeways, major avenues and intersections, as well as Grand Central Station and the Staten Island Ferry. Also included in this implicit strategy are attempts to shut down major public events; marches through or disruption of department stores; small groups of people blocking bridges or commuter train lines; and, to a lesser extent, simply dragging barriers into the street (the general tension within these tactics is explored in section two). As other comrades have pointed out in previous contexts, it is no surprise that this surge of spontaneous intervention was directed toward shutting down the capillaries of commodity and human circulation and sites of “social reproduction” more generally.[2]

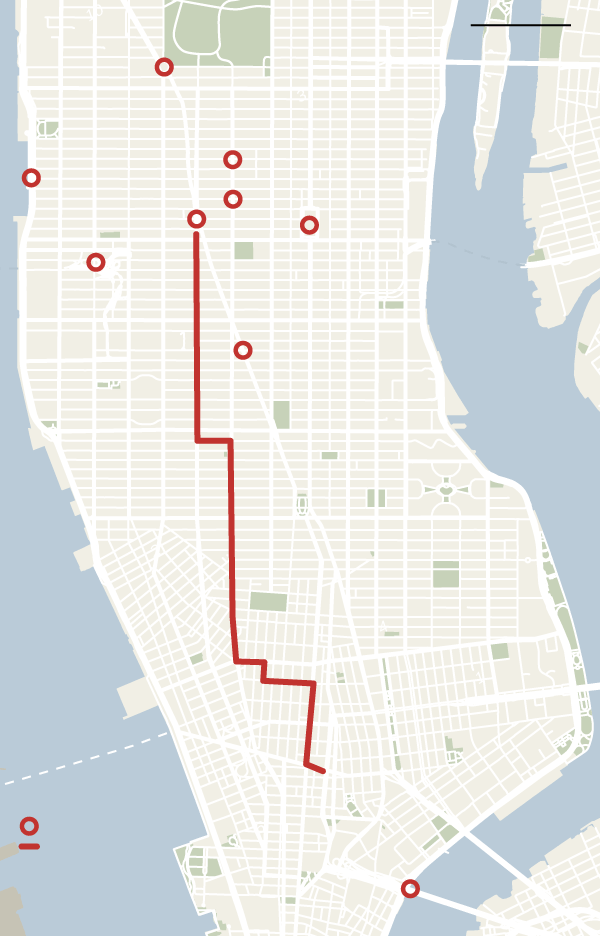

As in many other cities, the first major night of protest immediately followed the verdict not to indict Darren Wilson for the killing of 18-year-old Michael Brown. Hundreds, and then thousands, gathered tensely in Union Square to await the grand jury announcement. As news spread throughout the crowd of the non-indictment, people began to pour into the streets, disobeying NYPD injunctions to remain on the sidewalk. Despite the energy in the air, the night at first began to follow an all too familiar sequence: a rowdy and potentially unpredictable march weaves its way through the city, blocking traffic and gathering energy, before being led to Times Square—confronting blaring advertisements, confused tourists, and hordes of cops before the momentum dissipates and people begin to disperse (or the police decide to disperse them). Instead, the evening took a dramatically different turn, providing a glimpse of what was to come. While the march milled about Times Square, one protester spotted Police Commissioner William Bratton, responsible for implementing the controversial broken-windows and stop-and-frisk policies, and doused him and the officers surrounding him with fake blood. Soon after, in an apparently spontaneously decision, the huge crowds decided to break with the organizers and continue marching. By the end of the night they had blockaded the Triborough Bridge, connecting Manhattan to Queens and the Bronx, and marched over the Brooklyn Bridge.

Although national attention was rightly focused on the responses in Ferguson, the scale and militant tone of the mobilizations in New York City surprised many, and continued to intensify. The next evening, thousands of people comprising several different marches moved through the streets of the city, blockading major choke points (large avenues and entries, and moving on before the police could interfere). If on the previous night protesters had shut down bridges in a spontaneous or impulsive fashion, by now blocking major traffic arteries had become a widely held and articulated strategy.[3] While some assert that the actions, targets, and routes were discussed in advance, the bulk of what unfolded appears to have been largely improvised. By the end of the evening, traffic at numerous tunnels, bridges, highways, freeways, and major intersections was brought to halt, with only 10 arrests taking place.

One group marched through the housing projects on Avenue D in the Lower East Side, to cheers of residents and—road flares ablaze—flooded onto the FDR Expressway, the major thoroughfare along the east side of Manhattan. They later clashed with police trying to take the Williamsburg Bridge, before marching over the Manhattan Bridge into downtown Brooklyn, blocking one of the busiest intersections in a four-and-a-half-minute-long moment of silence. Another group marched over the Westside Highway and Riverside Drive. Yet another blocked the entrance to the Lincoln Tunnel, connecting Manhattan and New Jersey, and then marched across the city to also block the FDR after the first blockade had proceeded over the bridge. This duplicate blockade of the most important east-side highway in NYC appeared utterly remarkable to those who had left the FDR moments before. Before November, it would have been inconceivable to think that this syncopated blockade could be pulled off, especially as a largely spontaneous action (such is the nature of the current moment).

****

With another grand jury decision slated for the following Wednesday, few predicted how (or if) the mobilizations associated with #blacklivesmatter would continue. This time, the legal decision was much closer to home: Officer Pantaleo’s killing of Eric Garner in front of a grocery store, which had already prompted a well-publicized protest months before, stewarded by Al Sharpton. Just as in Ferguson, the grand jury announced (on December 3) that no criminal charges would be pursued against Officer Daniel Pantaleo. This time, the slow, excruciating strangulation of the asthmatic 43-year-old man was filmed and had gone viral in the preceding days. Garner’s final plea (“I can’t breathe”) would become the new slogan in the emergent anti-police brutality discourse signaled by “#blacklivesmatter” and the tactics signaled by “#shutitdown.”

In nearly identical fashion to the previous week, the night following the announcement of Pantaleo’s non-indictment saw thousands flooding the streets in semi-spontaneous fashion, followed by second night of large-scale marches coordinated by various NYC political groups. As in the previous week (and the weeks to follow), the marches did not follow a predetermined route, nor were the targets of the huge marches plotted in advance. Once again, the actions in New York City were the largest instances of the tactical arsenal implied by #shutitdown: massive marches that closed roads and highways for hours, temporary blockades of public infrastructure, and transient disruptions of businesses and public spaces (performative boycotts labeled “die-ins”).

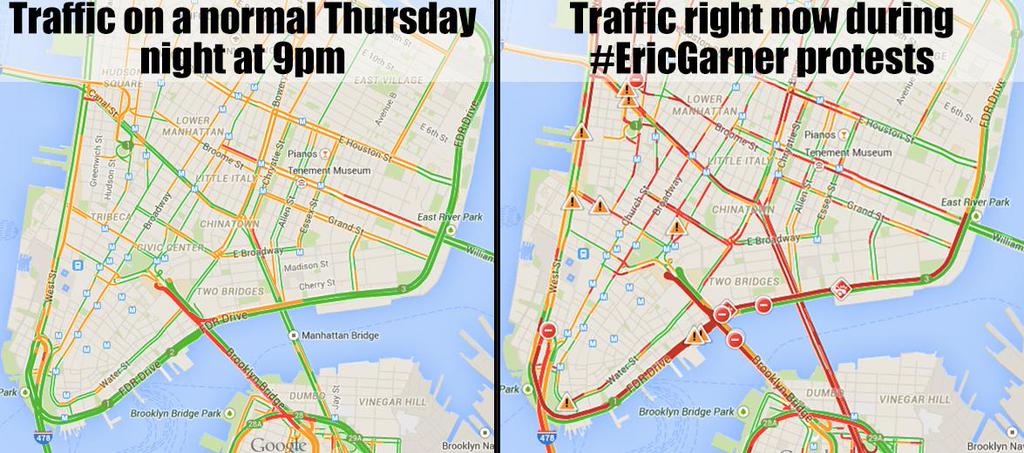

It is difficult to convey the enormity of the marches and blockades on the nights of December 3–4. Multiple marches of thousands gathered in lower Manhattan and fanned out across different parts of Manhattan to a common group of targets, including the West Side Highway and the FDR Highway (the two major arteries of vehicle traffic in the city), as well as the bridges that connect Manhattan to Brooklyn and Queens (the Manhattan, Brooklyn, and Queensboro bridges were strategically blocked by massive marches). Major streets and avenues were also shut down in Manhattan and Brooklyn, bringing vehicle traffic in much of lower-and mid-Manhattan to a standstill into the early morning on both nights.

Added to this was the attempt on Thursday night to storm the Staten Island Ferry. Aside from its symbolic and real connection to Garner (where Garner allegedly sold untaxed cigarettes for a living), the Ferry is an important node of transportation in the metropolitan area. Although there were more arrests than the previous week, by NYPD standards arrests were on the light side, with around 100 per night. The sheer energy of the bridge takeovers surprised and impressed everyone who followed them, with thousands of protestors bearing #ICantBreathe signs, symbolic caskets, and pure rage shutting down traffic for hours,[4] while drivers honked or blasted music in solidarity.

The Monday following the Eric Garner verdict activists in Staten Island surprised many by blocking the Verrazano Bridge, which connects Staten Island to Brooklyn.[5] However, the density and militance of street mobilizations declined sharply after December 4, as smaller actions continued night after night (as we will see, these actions moved away from blockades and toward die-ins). For radicals in NYC, many of whom have been organizing against state violence for years, the Millions March appeared to be a decisive moment in the #blacklivesmatter movement. In reality, the situation had already changed before December 13. The non-profit organizations and movement “managers” had made more headway leading marches after December 4. They were able to do so, in part, because the spontaneous energy had exhausted itself during the two successive weeks of response to the (non)verdicts on the murders of Michael Brown and Eric Garner. As the mobilizations in the streets waned, these same managers[6] would be the beneficiaries of the NYPD’s absurd state of emergency (aided in doing so by NYC’s mainstream media outlets).

We must emphasize the extent to which the mobilizations in this period ran ahead of even the most radical wings of the organized left. One of the few exceptions—the break-away march that split from the Millions March—proves the rule: despite its high intensity and militant chants, it lasted little more than 20 minutes and failed to spread beyond people already affiliated with NYC’s radical scene. If anything, the Millions March served to highlight the increasing distance between the radical scene and militants that are organically part of anti-police (or anti-police brutality) movement. Moving forward, one of the pressing questions for the anarchist and left-communist milieu will be how to build tangible relationships with the new militants coming out of this cycle of protests.

In any case, the swan song of the bridge blockade in the November–December cycle was the unplanned finale to the Millions March. Following the media-friendly 40,000-person parade through mid-town Manhattan to City Hall, thousands overran the police barricades and stormed the Brooklyn Bridge. Continuing through Brooklyn, the massive group made its way past the Barclays Center on Flatbush Avenue, through Crown Heights via Eastern Parkway, and finally to the Pink Houses in East New York (where another unarmed black man, Akai Gurley, was killed outside his apartment weeks earlier). As it stood, the radical pole of #shutitdown entered into decline before any sustained blockade or occupation was attempted (or for that matter, before the formation of new networks capable of combating the ascendant non-profit groups).

At the time, many hoped that the burgeoning “shut downs” might lead to a larger social and political rupture that had not been seen in NYC for decades. Would the current movement open the first fissure in NYC’s incomparably powerful and extensive police-state? Unfortunately, subsequent developments have called such forecasts into question, as the density and spontaneous militance of the blockades ceded ground to the other tactic that has come to characterize #blacklivesmatter: the “die-in.” Although the die-in and the blockade have been continuous factors since the events in Ferguson exploded onto the national level, we note that the prominence of the latter (following responses to the verdicts on the deaths of Michael Brown and Eric Garner) waned relative to the former. Both exhausted and lacking in any conceivable direction forward, the large mobilizations diminished in size and changed in character and tone.

****

For its part, the die-in aspires (on the one hand) to a disruption that re-enacts scenes of police murder within spaces of civil society that are normally sheltered from the regular barbarities of racial and class-based violence. On the other side, the tactic is a kind of didactic theater, communicating a message[7] on police brutality to oppressors and oppressed alike. The common targets for die-ins have included luxury retails stores (like Macy’s or the Apple Store on 5th Avenue, or Brooklyn’s Barclays Center), hubs of human and commodity circulation like Grand Central Station and Times Square, and of course the blockaded streets themselves. To the surprise of many, it has progressively become common sense that “diversity of tactics” is an integral part of most historical movements that have changed society. Existing alongside and supplementing more aggressive forms of protest (road occupations, blockades, even urban riots), the die-in has played a useful role in the post-Ferguson cycle (and not only in NYC). However, as the more militant, “practical” dimension of the street protests faded, the preponderance of the die-in shows the extent to which the previous mobilizations had become largely symbolic; rather than spontaneous efforts at disrupting or challenging the police or the flows of commodities, these demonstrations risk becoming mere appeals to the state for reforms that it will not and cannot concede. Although we cannot explore the issue further in this account, considered strategically, we call attention to how the die-in might shed light on a fundamental tension within both the discourse of the movement emerging after the killing of Michael Brown (#blacklivesmatter) and its tactics (#shutitdown).

In any case, the enormous volume of demonstrators and the hydra-like multiplicity of actions—along with an unprecedented degree of broadly anti-police popular sentiment—largely neutralized NYPD efforts to control the demonstrations. Much has been made of the mayor and police chief’s “hands-off” response to the protests over the last few months; following the murder of two officers in Bed-Stuy December 20, mainstream political opinion would have it that de Blasio’s waffling and Bratton’s foolish benevolence simply allowed the protests to happen.[8] Nothing could be further from the truth. If anything else, de Blasio was simply caught in the classic liberal double-bind: elected on the pledge to repair the enormous rift between police and communities of color through toothless reforms and pledges (e.g., community policing and formulaic officer retraining), he was powerless to contain the rage of his supposed constituents in the face of Ferguson and Eric Garner’s on-tape murder. On the contrary, the mayor’s middle-ground position simply made him an easy target for the aggressive reactionaries in the policemen’s union, especially after two officers were shot and killed in an unrelated incident in Bed-Stuy on December 22.[9]

Much has been made of the supposed “war” between city hall and the NYPD[10]—far too much in our opinion. To be sure, the degree of police repression against New York activists and even anti-police sentiment is perhaps unprecedented.[11]However, it is equally apparent that the wailing and fearmongering of the Patrolman’s Benevolent Association and local media outlets have not succeeded in turning the political tide in their favor. Two weeks of the farcical NYPD “strike,” whereby officers refuse to respond to petty crimes like parking violations and public urination, has not only failed as a political gesture; for many, it has also contributed to the broadly anti-police sentiment that continues to generalize within certain strata of the population following Ferguson.[12] Within the current hostile police environment, it is clear that new developments may be required for the movement to regain its earlier intensity, whether at the level of tactics, ideology, or movement composition. It is difficult to say whether the spontaneous and militant series of mobilizations in NYC, following the logic of #blacklivesmatter, will continue to be such a vibrant force as has been seen in the past two months.

- [1]The ratio of NYPD victims to indictments is 179 to 3.↩

- [2]On the logic behind circulation-side struggles in the current historical moment, see Endnotes, “Logistics, CounterLogistics and the Communist Prospect ” and Theorie Communiste, “The Glass Floor.”↩

- [3]The blockade, adopted from and in solidarity with Ferguson, had spread to 170 cities by late November.↩

- [4]A communique made after December 4 evokes the general atmosphere.↩

- [5]Besides housing many working-class people of color (like Eric Garner), Staten Island is also the home to a large number of New York’s finest.↩

- [6]The group primarily taking the lead is called (without an ounce of irony) Justice League NYC.↩

- [7]In this way it is similar in form and content to other recent initiatives arising in the wake of Ferguson, such as the Black Brunch protests. More on the larger question of new black activist organizations.↩

- [8]The right-wing sycophants at the New York Post have pushed this incomprehensible notion the hardest. Recently, Commissioner Bratton has tried turning the tables, blaming the Bed-Stuy episode on the protests of November and December.↩

- [9]Once again, the NY Post fired the opening shots.↩

- [10]In light of the ongoing tension between the NYPD’s union and Mayor de Blasio, the present moment has also been compared to the anti-police riots and PBA publicity stunts of the early 1990s.↩

- [11]As is well known, forms of surveillance based on social media have largely replaced the police tactics such as stop-and-frisk (this was one of Mayor de Blasio’s benevolent reforms). In NYC and Ferguson alike, expression of anti-cop sentiment has been enough to merit terrorism charges.↩

- [12]In addition to the communities of color that have suffered from structural police violence for generations, this outlook become increasingly popular among the downwardly-mobile generation of “millenials.” See also Paul Mason’s analysis of the role of the “graduate without a future” in the Occupy movement in Why It’s Kicking Off Everywhere.↩