We first went to Occupy LA Sunday, October 9, 2011. “We” is the Palm Tree Proletarians, a loose group of anarchists and left communists in Los Angeles.

The Beginning

Amiri

None of us are camping out there; we all have work, school, children, or all three. That first Sunday we arrived around 2 pm, and the crowd appeared very lively. It’s important to understand the geography here: the demo is mostly on the front lawn and back lawn of City Hall, a building that occupies more or less a whole city block. A large city block. There is a very broad east–west street in front of City Hall, 1st Street, and directly across 1st street, to the south, are two other municipal buildings. One of them just happens to be the LAPD headquarters.

The other is the headquarters of the California Transportation Department, District 7. Both are quite sinister: the first in content, the second in form. The cop station is postmodern glass and stone, and looks like a modern office building. Inside is the most brutal and corrupt police force in the United States, after the NYPD, of course. The transportation department looks, frankly, like the Death Star, or what you imagine the Ministry of Love would look like. Its Leeds Platinum Award–winning, energy-saving design, slate gray color, matte, nonreflective material, and perforated dark aluminum gliding panels give it the appearance of nothing so much as a blocky robotic bat perching, slowly admiring its wings, fangs, and claws, as the panels slide around and open and close with the motion of the sun. Of course, both are fronted by enormous concrete plazas of Baron Haussman breadth, a sliver of sidewalk telling you where 1st Street actually begins.

Across the street is Occupy LA. There are tents covering every grassy space, young women in Chicken of the Sea mermaid costumes holding colorful sparkly blue banners decrying the damage wrought by industrial tuna fishing, other activists and onlookers walking around. There is not a crowd of “normal” people just walking around, perhaps because this is downtown Los Angeles on a weekend.

It clears out mostly, and this is the municipal center, not the commercial center of the downtown area. The sidewalks along either side of City Hall, leading to the rear, are concrete, no good for tents. People set up little tables and benches, but it’s difficult to occupy the sides of City Hall. Most people hanging there are just hanging out, taking a breather. The fire department is in the same building as City Hall, and you see its main entrance when you walk on the east side of the City Hall building, north, toward the rear lawn. The street behind City Hall is called Temple, and so, behind City Hall, across Temple, to the east, catacorner the City Hall building, is Fletcher Brown Square, which resembles a park. You can see inviting grassy knolls from a block away, but when you approach, you realize that only the elevated rim of the park is grassed. It’s really a concrete bowl, and it is mostly used by homeless people, who sleep on the concrete benches when other homeless have taken all the soft grassy spots around the rim. Which is one reason why it hasn’t been occupied as well, being a “vacant” area so close to the official occupation. And I do mean official occupation.

On October 9 there were two other events in downtown Los Angeles: one was a 10-mile bicycle demonstration that went through downtown, and passed in front of City Hall. The other was a series of events around the 14th annual Hispanic Heritage month. We saw the cyclists, but we did not see the Hispanic Heritage events, except for extra police presence east of Los Angeles Street on the drive north to City Hall from the freeway. There were also some streets closed off, but it was impossible to tell exactly why.

We parked a quarter-mile away and walked the rest of the way north, and we heard that there was a soundstage before we rounded the corner of Los Angeles and 1st Street. We could hear the pretty awful amateur folk music as we came closer. The first singer we heard was singing that we need a “love forcefield.” And then he started to preach, or teach, that the only thing that exists is love. “Love is all there is.” I don’t know who else feels that way, but it was pretty silly. I am still not sure who runs the stage day to day, but we P.T. Proles found each other by walking through the crowd, calling one another’s cell phones, and texting locations. We found Hector, David, Chris and Stacy (and their two boys) on the grass slope near the stairs to the stage. In the crowd were people listening to the singers, watching the stage, roaming about, checking out the literature people had brought, stopping to talk with the people who set up placards or tables, etc. There were not many of the classical sects present, or at least they didn’t have booths and “centers” set up. So much of the literature was populist or American liberal in orientation, as were many of the signs: “Banks got bailed out—we got sold out,” and “Money is Not Speech,” the latter a reference to the Citizens United Supreme Court Case (558 US (2010)), in which the Court finally just let it be known that money is indeed First Amendment speech.

There were several thousand people in front and back combined, but the crowd did not seem to be overflowing into the streets: the very broad, wide streets surrounding City Hall. The folk music stopped shortly after we PT Proles got together. An emcee took the microphone and big-upped the LAPD, saying that they were also part of the 99 percent, and that they had been helpful, etc., before relinquishing the stage to a man who warned us that he was about to get serious and technical about “the economy.” He wanted to explain to us the history of how things got this way. He started talking about the Glass-Steagall act, and how we needed to bring it back.

It was almost impossible for us to hear one another over the noise, so we moved to the back of the building. We would later realize there was a message in this medium: constant, deafening noise—music, lectures, etc.—from a “stage” at the top of the City Hall steps, directly above the fountain and concrete plaza bisecting the front lawn. This was not a place for any sort of discussion among the “party people,” which is how more than a new speakers and performers addressed the occupation. At the rear of the building there was a Chicano nationalist dance troupe performing in the middle of Temple Street, decked out in full indigenous regalia. They had drums, so we still could not talk to one another. The rear lawn was totally covered with tents, to the very edge of the grass, where the sidewalk began. We saw Fletcher Brown Square across Main Street and headed over. The wind was blowing that day, but much like the Los Angeles basin in general, the odors of the homeless sort of hung in the air despite the breezes back and forth. We found a spot under a tree recently vacated by one of the homeless people and started discussing what we should do. Chris and Stacy’s two boys jumped from bench to bench, between and among the dozing or dazed homeless, playing hide and go seek and various other games, while we decided what, if anything, to do.

I say “if anything” because if you’ve been to a demonstration in the United States since 9-11, you know what this one was like. The costumes, the dancing, the drumming, the American liberal swamp. Most of the people at Occupy LA so far have been college-age activists, middle class liberals, soft lifestyle anarchists and homespun populist philosophers. There is also a strong current of what you might call “hippies,” too, if I can be so anachronistic. Tie dye and spray paint. The only difference from the classic 2000-era demonstration was the lack of the sects and the presence of… the “libertarians.” You know, those reactionary Jeffersonian blowhards who think that a smattering of European political philosophy makes them something other than run-of-the-mill Babbits and race-baiting Reaganites. Who are trying to cope with the traumatic realization that the government is not only their enemy only when it’s giving “their” tax money to “welfare cheats,” “illegal aliens,” and “urban areas” (all of this is still quite “raced,” of course). I didn’t see any that first day, but I didn’t explore every nook and cranny, either.

We P.T. Proles decided to make some signs for next time. Our idea was that we might throw some salt on the wounded liberal outlook, tweak their disappointment with Obama, poke the quicksand and scum floating atop the liberal swamp, and thereby meet some people who already feel the limits of this, who want a firmer critique. That’s about all we have at the moment. Occupy LA is not a revolutionary uprising for several reasons, but that doesn’t mean revolutionaries can’t come out of it. And we, the atomized, un-self-conscious working class, do learn: a worldwide wave of demonstrations, like the Occupy Everything Movement is turning out to be, is its own very important lesson that no one should underestimate: there are others “like us.” Many more than you thought. We hope to help others to recognize that the others are not “we the people,” not “citizens,” not “taxpayers,” and certainly not “consumers,” but workers, separate from the unions, separate from the politicians and their parties, separate from “we the people.”

We came back October 16. On the way into downtown Los Angeles from West LA, we took the freeway, missed our stop, and had to get off at Maple. We drove up Maple, from I-10 (around 15th or so street) to 2nd Street. Apparently, Sunday is a big shopping day along this street, because it was packed, like you see pictures of Calcutta, packed—pedestrians in the street, traffic slowed to a crawl, informal traffic officers (really barkers for the various storefronts and parking lot operators) standing in the middle of the mayhem, attempting to guide drivers to one or another underground parking structure, or to wave you on through, thousands and thousands of people, 99 percent Latino, a handful of blacks. This crunch of shoppers, individuals, groups of teens, whole extended families, all doing their weekend shopping, mostly for clothes, perfume, electronics, knickknacks like that—there were no food or grocery stores—was about 4 blocks long.

Occupy LA was quieter. The sound amplification wasn’t as loud. The folksingers were more subdued. There were longer silences from the stage. I still don’t know who runs the stage practically, but I assume it’s members of the committee that got the permits and that “liases” with several LA City Councillors. And who ensured that, four days into the occupation, October 5, Mayor Villaraigosa felt comfortable enough to come and hand out rain ponchos to the demonstrators. While refusing to buy city library workers office supplies (one of the Proles works in the city libraries). They’re doing a terrible job with that stage. It has to be said. That same committee also isolated the anarchists among the core instigators of the occupation in those first crucial days, before mayoral candidate and City Council president Eric Garcetti told the occupation to “Stay as long as you need, we’re here to support you.” The Democrats and the Occupy LA committee have made it so that calling the occupation “a bunch of hippie anarchists” is becoming something of an ironic in-joke among hip supporters of the movement, as if to say “Well, if Obama’s a socialist, so am I, goshdarnit!”

Anyhow, in the crowd on October 16 were more union members. There were no actual union delegations besides the Wobblies. They’re not quite the AFL-CIO, though, are they? Or the United Teachers Los Angeles, a 40,000 member union of the Los Angeles Unified School District, which has been pummeled year after year with budget cuts and layoffs. UTLA “encouraged” its members to support the occupation as individuals. We met two comedians, one of whom was a member of UTLA, and told us about this encouragement. The other cracked jokes about the Bob Marley–impersonating folk singer on stage. There were also many individuals from the state university teachers’ union. While Ryann and I waited for the rest of the Proles, we chatted up a group of Wobblies till they retired to the rear of the building for a lecture on Workers’ Rights in the 21st Century for the 99 Percent.[1]

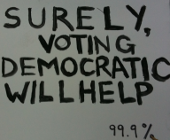

We made our first sign. “Surely, voting Democratic will help,” signed, the 99.9 Percent. We put it in the sign area and camped a little ways back up the hill. It turns out that people actually stop to read the signs. It’s a little hard to walk around with a sign, because there’s not a real parade area, and the space is so packed with bodies, tents, and bodies in tents. There’s not really a place to go. One puts one’s sign down, and walks around and talks with folks. Hector and Anita finally arrived, and told us about a woman who had been harassed a couple of minutes ago. She had been selling hot dogs on the sidewalk, and she was surrounded and harassed. By who was not clear. I asked if she was a police officer, and Hector said no, she was just a street vendor. See, street vending… is illegal. Yes. Illegal. Of course, you can’t walk a block in certain neighborhoods without seeing a street vendor, and you can’t drive a mile in any neighborhood without seeing a street vendor. I was confused.

We made our first sign. “Surely, voting Democratic will help,” signed, the 99.9 Percent. We put it in the sign area and camped a little ways back up the hill. It turns out that people actually stop to read the signs. It’s a little hard to walk around with a sign, because there’s not a real parade area, and the space is so packed with bodies, tents, and bodies in tents. There’s not really a place to go. One puts one’s sign down, and walks around and talks with folks. Hector and Anita finally arrived, and told us about a woman who had been harassed a couple of minutes ago. She had been selling hot dogs on the sidewalk, and she was surrounded and harassed. By who was not clear. I asked if she was a police officer, and Hector said no, she was just a street vendor. See, street vending… is illegal. Yes. Illegal. Of course, you can’t walk a block in certain neighborhoods without seeing a street vendor, and you can’t drive a mile in any neighborhood without seeing a street vendor. I was confused.

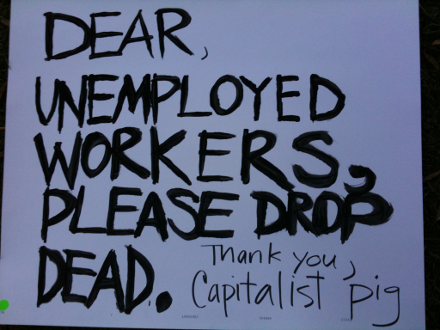

Anita and Ryann went off to go get water while I finished blocking out the sign. Hector came up with several more sign-making ideas and an idea for next week, to amplify the message of discord with the bland liberal booshwah: we would set up a mock guillotine and put a wishlist beside it. At the end of the day, we would read the list and execute something in effigy. A vegetable or something inanimate, of course. It’s not about encouraging violence, but about confronting this reflexive, self-defensive nonviolence. Prophylactic Ghandiism, as though that will stop cops from cracking heads. Or win a better world for the alleged 99 percent. Ryann made our next sign: “Dear Unemployed Workers: Please drop dead. Love, Your Capitalist Pig.”

Anita and Ryann came back with a clarifying, if not edifying tale. They had walked around the corner, along the western sidewalk of City Hall, toward the rear. They came upon another street vendor being harassed. This time, it was a 15-year-old girl and her mother selling sodas. Who was harassing them? Members of the Occupy LA Security Committee. When Anita and Ryann came upon the scene, two male demonstrators were commiserating with the teenage girl, who had actually been lightly assaulted by another female demonstrator: Some Occupy LA demonstrators surrounded the girl and her mother, and told them they were going to ruin the occupation. How you might ask? By violating the City Health codes. In their numerous agreements with the City, the Occupy LA committee made it clear that they wanted to abide by every law and regulation, including city health inspections of their Food Tent operation. If street vendors were found in the area, that could be a violation of the Committee’s permits and legal standing, and the whole demonstration could be found unsanitary and unhealthy, a danger to the public and, more important, the demonstrators themselves. So, these citizens of the Occupy LA demonstration, many of whom have left their homes and sleep in the park, voluntarily homeless for the duration of the occupation, descended quickly upon these illegal (and presumably illegal) interlopers, to purge the occupation site of their deadly soft drinks. The female demonstrator took out a camera and began filming or taking pictures of the girl, and the girl raised her hand to block the pictures, and the woman slapped or pushed or moved her hand out of the way. The woman told the girl that she and others were going to put her picture all over the Internet, denouncing her as an enemy of the occupation, which they did. The girl became furious and started crying. And her and her mother were surrounded by other Occupy LA people by now, and then Occupy LA Security arrived: two men in yellow fluorescent vests, accompanied by a woman, not in a vest. They told the demonstrators to “disperse.” Oh boy. My comrades looked at them like they were crazy, and continued to talk to the girl. They advised her to go before the police showed up, and she and her mother left the scene. After getting their water, Anita and Ryann came back to open up a dialogue and to find out just who these maniac demonstrators think they are and what they think they’re doing telling people to “disperse.” They spoke to the two in the fluorescent vests.

“Why are you picking on this lady and her daughter, who are selling drinks for their survival? And why are you talking like a cop?” asked Anita.

“That is just a better way to say it than ‘get the fuck out.'”

The other security officer said that it was an appropriate word to use because it was in the dictionary, and he advised them to look it up.

“We have to make sure that the area stays clear of illegal activity.They’ll use any excuse to shut us down.”

“When the police want to come and disperse the occupation they will, and it doesn’t really matter what you do. Harassing street vendors will not keep the cops from doing whatever they want,” said Ryann.

“We have to protect the demonstration from reprisals.”

“So what are you worried about exactly? Crossing all your t’s and dotting all your i’s? So you can say that you did everything the law told you to do when the cops come and tell you to leave?”

“Yeah, we can’t give them any excuse! Some of us have been here all night and day for weeks now. Some people who come here are just weekend warriors. We’re trying to protect our demonstration from illegality. Are you sleeping here?”

Ryann plunged a mock dagger into her own heart and staggered back, stumbling.

“We’re just trying to protect our demonstration! We’re here, we’re occupying, and we want it to be successful! We are trying to help those street vendors but they are jeopardizing the occupation and could cause our food tents to be shut down by the Health Department!”

“Look!” said Ryann. “Right across the street is the police headquarters! You think that they won’t come and ‘disperse’ you if only you keep street vendors off the sidewalks? They will come in here and move you out whenever they goddamned well please! You think that because you obey health regulations they won’t move you out when they want to? What, do you want to make sure you have records of your fastidiousness… for what? Are you going to sue the LAPD? When they come and move you out? For whatever reason they make up?”

The security guys blinked.

“There are cameras everywhere. You are being watched. You think you’re occupying, but you’re occupied.”

The security guards’ eyes grew wide. They had never thought of it that way before. It sounds like they had never thought of it at all before.[2]

Hector joked that Occupy LA just might turn out to be the vanguard of the next wave of gentrification of downtown LA. “See? They’re already claiming ownership of the space, and they think they’re tough ’cause they can say, ‘Hey, I was homeless downtown for a month!’”

Our next sign revealed our new insight: “State Certified Temporary Autonomous Zone!© Vote Democrat 2012!”

Our next sign revealed our new insight: “State Certified Temporary Autonomous Zone!© Vote Democrat 2012!”

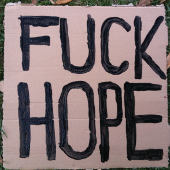

Anita remained pissed off, and commented on how she kept seeing young Latinos come in to check things out and then promptly turn around and leave. She couldn’t tell whether it was the awful folk music or the Santa Monica wanna-be hippies. Her idea for the next sign was a direct jab at the liberal colonialists: “Fuck Hope.”

Hector and I had to go to the bathroom next, so we walked around the same way Anita and Ryann had gone. There was an interesting demonstration that aligned with his effigy execution idea: an artist had put out a series of pumpkins, marked with pictures of favorite leftist boogeymen like Dick Cheney, John Ashcroft, people like that. Barack Obama was nowhere among them. We definitely have to execute some vegetables next week.

Hector and I had to go to the bathroom next, so we walked around the same way Anita and Ryann had gone. There was an interesting demonstration that aligned with his effigy execution idea: an artist had put out a series of pumpkins, marked with pictures of favorite leftist boogeymen like Dick Cheney, John Ashcroft, people like that. Barack Obama was nowhere among them. We definitely have to execute some vegetables next week.

After circling around the building, we came back to our base by the stairs. After passing a dreadlocked black man on the curb spraypainting T-shirts with the stenciled slogan‚ Love Is All There Is, we found Ryann and Anita in intense conversation: Ryann with a man with a portable easel and paintings packed on his back, and Anita with some comrades from South Florida we had met earlier.

You know the guy who has been harassed by the LAPD because he makes paintings of banks on fire? Alex Schaefer. He’s a real tool.

Ryann went over to speak to him upon recognizing him from the news. She quickly discovered that he is a “libertarian”—it irks him that people think he is a socialist or a communist because of his work, and he wants everyone in hearing distance to know it. She and a passerby named Ed, an ISO member, were trying to explain the difference between communist and state capitalist, but he kept going on and on about totalitarian Russia and China. I went up to see what all the fuss was about, and Ryann was telling the man to read some history before going on about solutions for the economic crisis. I listened for a while, and then jumped in when he started talking about how we need to abolish the Federal Reserve before we do anything else. Then we can cut the military budget, etc. One of the comrades from Florida said, “Hm… that didn’t work in the nineteenth century. What makes you think it will work today?” I asked Alex “Yeah! What makes you think abolishing the Fed will help anything?” He went on about controlling the money supply. I asked him “Why is controlling the money supply so important?” He didn’t know what I meant, really. I asked “Who benefits from fluctuations in the money supply?” He said “Crony capitalists of the government bureaucrats.” I said, “But why do they control the government?” “Crony capitalism.” “But where does it come from?” He didn’t know how to answer. “Concentration of capital, right?” “Yeah, concentrated wealth and power!” “How did things get that way?” He didn’t know how to answer. He said something about free market competition. “Yes, but the free market leads to concentration when somebody wins, right? Which is why the Fed was established in 1913?” Then he raised his voice and began preaching to the sky about how 1913 was Armageddon for the small businessman, and it was the beginning of the decline of opportunity for the little guy and how we need decentralized control of the money supply. Like an idiot William Jennings Bryan. Several low-brimmed characters had gathered by now and started muttering about other secret financial arrangements of this same group of bad guys going back to the French Revolution. Nobody said it, but they were talking about the Illuminati, of course, an underground group of German bourgeois revolutionaries, since become masters of the universe for a certain set. Alex calmed down and I asked “Well, why in 1913 did this group suddenly succeed in establishing this horrible power over us?” None of this kind of “libertarian” knows any history. They don’t think that way. Of course he didn’t know what I was talking about. “Maybe changes in the actual economy, in real material history of the growth of capitalism through the real hundred years of the nineteenth century required some sort of regulatory mechanism for big capital, finally, like the Federal Reserve? Alexander Hamilton didn’t succeed in setting up a Fed after the American Revolution. What changed? Something obviously changed to where they could succeed, right?” The cipher disintegrated after that. I wish I could remember all the names of the conspiratorial meetings and conferences people were bringing up. Most in the interwar period. Real secret history stuff.

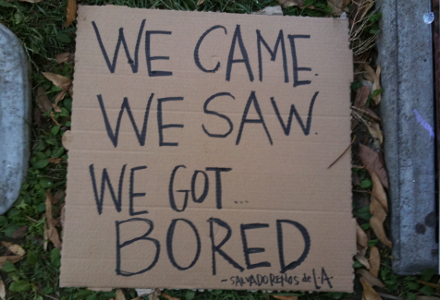

Hector had had enough, and Anita made this sign. (Hector signed it Salvadorenos de LA.)

Ryann gave up shortly after that, too, and we returned to our campsite. It was getting cold, but we were gratified that our signs had attracted a lot of attention. People laughed at them, and even stopped to hold them up to take pictures with them! Especially the capitalist pig sign. One pair of Indian men posed with it, and Anita and Ryann chatted them up. They talked about all sorts of things, and one of the things the men brought up was how difficult parking was around here. It was also confusing because the benches and tables along the eastern side of City Hall looked a little too official—official enough to give someone the impression that there might be valet parking.

That’s the last sign we made October 16. Ah, détournement.

The End

Ryann

As the weeks went by, we watched the occupation turn from a meeting place and protest site into a tent city. If you were not camping overnight, there was increasingly no space for you on either side of City Hall park. Political discussion and people willing to discuss political issues seemed thus literally crowded out as well. The tent encampment became an end and not a means of further organizing. An occupation once filled with liberals, libertarians, anarchists, and anticapitalists of all denominations was drained, and, by the end, the only thing passing as political discourse was the mad ramblings of conspiracy theorists and libertarian types. Although we met some members of a newly formed anticapitalist affinity group the weekend of October 23.

On that Sunday, October 23, the meeting area that we had previously used was now covered in tents, and the signs that had garnered so much attention on our last outing were laying piled up near the trash. We placed our rescued signs under the trunk of the tree now serving as our meeting place. Our objective was to make more signs highlighting opposition to the prevailing liberal and libertarian rhetorics that had come to dominate the occupation’s political speech. We met and spent time making signs with Temper Goldie, one of the homeless occupiers.

Unfortunately, our signs did not generate the kind of discussion they did before. There was less political activity, fewer petitions, and less speech in general going on in the camp. A great deal of drumming, theater, and dance was performed on the concrete plaza in the middle of the front lawn—the only area not dominated by the tent encampment.

By Sunday, October 30, the middle class liberal element—like the mermaids and other green activists, and like the few “regular folks” who passed through the occupation in the first weeks—seemed to have vanished from the occupation. Perhaps suitable for the green types, their only traces were fundraising convention–style presentation booths—with highly designed graphics and placards explaining why you should donate to such and such new urban development or organic electric community—all unmanned.

Amplified by the sound system, the drumming and dancing was again intense and deafening, making speaking and hearing others extremely difficult in the front of City Hall park. I managed to speak with Temper, the homeless occupier we met the week before. She informed me that the occupation organizers had now begun to discriminate against the homeless that had joined their ranks. (A very large proportion of the occupiers of the front lawn were not “activists” but real, regular homeless people and Hollywood street kids, some of whom were also homeless, but young.) The communal showers had been removed and the organizers rationed the donated food and supplies. Now the best food and supplies were no longer available to the homeless occupiers. A violent incident involving her boyfriend and a mentally ill man left him hospitalized after being hit in the head with a metal rod. The occupation’s security committee refused to call the police afterward and discouraged Temper and her boyfriend from filing a police report because to do so would jeopardize the occupation’s continued encampment. We saw this same mentally ill man moments later raving, buck naked, in the middle of the “performance space” in front of the City Hall steps.

Temper had saved our signs from the week before from an overzealous recycler by attaching them to her and others’ tents. She was featured in Los Angeles Downtown News holding one of those signs. In fact, two of our signs made it into the publication. The signs reading “Maximum Occupancy 99%” and “Capitalism is working just fine, now what!” are ours.

There was no space available in the front of the park and so we ventured to the smaller, quieter, north side of City Hall. This small area housed numerous tents, the free library, and a small canopied lecture and discussion space about the size of a large tent, because it was in a large tent.

We set off to distribute a leaflet we composed: Occupy Everything: What Do We Want? (And Who is Us Anyway?).

Blank stares accompanied most of my attempts to speak with people while handing out the leaflet. I ended up talking with a woman who gave her name as Rockstar and a man identifying himself as DJ, their YouTube handles. Hector/Vlad saw me speaking to them and joined in. They were anarcho-libertarians documenting the occupation for their YouTube channels. We got into a heated debate about what communism means. Only a small portion of the conversation was documented.

After watching their video on YouTube, reading some of the sick and depraved comments, and realizing that we had no way to respond, we were struck by a flash of inspiration: Why not emulate them? Why not use our resources to establish a communicative pole for our ideas and those who think like us? It was hard to talk with most people about the leaflet we distributed, but among those who had something to say, they were surprised that a loose group of independent activists actually wrote something, originally, themselves, at all. That it wasn’t a dictum handed down from some central committee. At Anita’s house, we tossed around old scenarios about other demonstrations and occupations, and we thought of the Wobblies. Big Bill and the Magón brothers. Then the idea hit us: soapboxing. Sort of. We would set up a booth, table, or some sort of area, with a camera, in order to establish a level of seriousness in our discussion. Signed across our table we would have something like “Political Advice: The P.T. Proles Are: IN.” With a backward “r” or two, if we wanted to be humorous. Or something like “Ask A Marxist” if we wanted to be more serious. Those who wanted to participate would field questions from passersby, and we would have a barker, rotating. Yes, “Ask A Marxist.” Or something like that. The way we thought of it, having a booth, with a camera, where we were willing to engage in serious discussion, and put ourselves on the line, on tape, could possibly raise the level of the whole occupation, sharpen our understanding of how to respond to given lines of argument and questioning, and give us material to share with others online. We had finally discovered “what, if anything, to do,” and because it is not one-way communication, like YouTube comments, like the Occupy LA committee and its soundstage, even like our leafleting, it could actually be a transformative experience for us and our interlocutors.

We had our reservations, and some among us were more than hesitant about appearing on camera. The main thing, though, was just a nagging feeling that we might have missed our opportunity. The occupation had changed dramatically in just a few short weeks, and not for the better. But we all agreed to at least prepare to give it a shot, depending…

We packed up our camera and tape, Hector brought a tripod, and we set off for Occupy LA, Sunday, November 12. It turned out to be our last visit to the occupation. Unable to find any “unoccupied” area, we were forced to make our meeting on the stairs leading to the west side entrance of City Hall. This time even the conspiracy theorists were sparse; the drummers and dancers were less enthusiastic and numerous, and the general spirit of the encampment seemed dampened once more. It was just over. Whatever mood of hope or possibility there had been in the early weeks was definitively gone. Our planned intervention just didn’t make sense anymore. Not if we had to set up on the west side steps of the occupation away from all the foot traffic.

The mayor’s office had long since begun the threats of eviction. The court orders to halt the eviction were being filed. But obviously, with the police headquarters across the street from the occupation, the occupiers were already occupied.

In the two weeks between our last visit and the end of the occupation, the city made efforts to negotiate with the “organizers.” Unlike in New York, there were people who coordinated with the city, received permits, and collaborated with the LAPD. The city of Los Angeles offered the occupation “negotiators” a $1 annual lease of a 10,000 square foot office space near city hall, some farm land, and housing for homeless people who could camp on the land. But of course, the “negotiators” couldn’t actually deliver what the city wanted: for the occupation to quietly pack up, declare victory, and leave. The “negotiators” couldn’t possibly speak for everyone, and the negotiations broke down.

On Wednesday, November 30, the occupation campsite was removed by the LAPD. There were tunnels under the street from LAPD headquarters to City Hall. The P.T. Proles were not in attendance, nor was anyone we are affiliated with.

On Monday, December 12, the port of Long Beach was shut down. Anita’s friend Julio was in attendance. When he arrived at 8 am, the port was already shut down, and a massive traffic jam ensued. Julio did not see any organized groups or banners other than a couple of members of the ISO. Immediately after he joined the protest, the police gave the order to disperse, and many people left. The police were wearing riot gear without masks. This indicated to Julio that the police probably had no intention of using pepper spray or tear gas on the demonstrators. The crowd blocked the intersection and the police declared it an unlawful assembly. A young “Black Flag Anarchist” rushed a cop and hit him with a stick. The cops hit him and other demonstrators ran to rescue him. The cops allowed the guy to return to the group and did not pursue him. He was not arrested. Julio says there was no evidence that he was an agent provocateur. It was cold and raining and the weather got worse. By 9 am, there were a few hundred people remaining, and Julio left without incident.

- [1]By the way, this whole 99% thing has been irking me: Life isn’t cheap these days. Stuff like this makes people think that a family bringing in, say, $250,000 a year is rich. One of Obama’s recent tax schemes wanted to increase taxes for households bringing in $300,000 or more. But in a major city like Los Angeles or New York, that income means an average family can actually pay all its bills without worrying about what to cut, eat out sometimes without worrying about whether they’ll be broke at the end of the month, afford good health insurance (and the copayments), own a recent model car, afford the maintenance, and *maybe* buy a house. In marginal Park Slope. Or Hollywood. *Maybe.* Not in Santa Monica or Manhattan. And they can’t afford private school for the kids with that income. Yes, most human beings on the planet must get by with much, much less, but the top 1 percent of income earners is definitely not the ruling class. The ruling class owns capital, and doesn’t carry car notes and mortgages. It’s actually the 99.9 percent or something like that, that runs the joint.↩

- [2]There are pictures of this confrontation online. If you read the article and the slogans shamelessly photoshopped onto the images, you will note that the author shares the “protect our occupation from the illegal street vendors” attitude of the security officers.↩